Sepphoris

Sepphoris / Tzipori / Saffuriya

צִפּוֹרִי / صفورية | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 32°44′44″N 35°16′43″E / 32.74556°N 35.27861°E | |

| Country | Israel |

| District | Northern |

| Council | Jezreel Valley |

| Founded | 5000 BCE (First settlement) 104 BCE (Hasmonean city) 634 (Saffuriya) 1948 (depopulated) |

Sepphoris (/sɪˈfɔːrɪs/ sif-OR-iss; Ancient Greek: Σεπφωρίς, romanized: Sépphōris), known in Hebrew as Tzipori (צִפּוֹרִי Ṣīppōrī)[2][3] and in Arabic as Saffuriya[4] (صفورية Ṣaffūriya)[a] is an archaeological site and former Palestinian village located in the central Galilee region of Israel, 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) north-northwest of Nazareth.[5] It lies 286 meters (938 ft) above sea level and overlooks the Beit Netofa Valley. The site holds a rich and diverse historical and architectural legacy that includes remains from the Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, early Islamic, Crusader, Mamluk and Ottoman periods.

Sepphoris was a significant town in ancient Galilee. Originally named for the Hebrew word for bird, the city was also known as Eirenopolis and Diocaesarea during different periods of its history. In the first century CE, it was a Jewish city,[6] and following the Bar Kokhba revolt of 132–135, Sepphoris was one of the Galilean centers where rabbinical families from neighboring Judea relocated.[7] In late antiquity, Sepphoris appears to have been a predominantly Jewish,[8] serving as a spiritual and cultural center, though it also housed a Christian bishopric and maintained a multi-ethnic population.[9] Remains of a synagogue dated to the first half of the fifth century were discovered on the northern side of town.[10]

Since late antiquity, Sepphoris was believed to be the birthplace of Mary, mother of Jesus, and the village where Saints Anna and Joachim are often said to have resided, where today a fifth-century basilica is excavated at the site honouring the birth of Mary.[11] The town was later conquered by Arab Rashidun forces during the 7th-century Muslim conquest of the Levant and remained under successive Muslim rule until the Crusades. Before the 1948 Arab–Israeli War,[12][13] Saffuriya was a Palestinian Arab village with a population of approximately 5,000 people at the time of its depopulation. Moshav Tzippori was established adjacent to the site in 1949. It falls under the jurisdiction of Jezreel Valley Regional Council, and in 2022 had a population of 1,030.

The area where the remains of the ancient city have been excavated, occupied until 1948 by the Arab village,[14] was designated an archaeological reserve named Tzipori National Park in 1992.[15] Notable structures at the site include a Roman theatre, two early Christian churches, a Crusader fort partly rebuilt by Zahir al-Umar in the 18th century, and over sixty different mosaics dating from the third to the sixth century CE.[16][17]

Etymology

[edit]Zippori / Tzipori; Sepphoris

[edit]In Ancient Greek, the city was called Sepphoris[dubious – discuss] from its Hebrew name Tzipori, understood to be a variant of the Hebrew word for bird, tzipor – perhaps, as a Talmudic gloss suggests, because it is "perched on the top of a mountain, like a bird".[18][19]

Autocratoris

[edit]Herod Antipas named it Autocratoris (Αὐτοκρατορίδα). Autocrator in Greek means Imperator and it seems that Antipas named the city after the imperial title to honor the Augustus.[20]

Eirenopolis and Neronias

[edit]Sepphoris issued its first coins at the time of the First Jewish War, in c. 68 CE, while Vespasian's army was reconquering the region from the rebels.[21] The inscriptions on the coins are honouring both the emperor in Rome, Nero (r. 54–68), and his general, Vespasian, as they read 'ΕΠΙ ΟΥΕCΠΑΙΑΝΟΥ ΕΙΡΗΝΟΠΟΛΙC ΝΕΡΩΝΙΑ CΕΠΦΩ' meaning 'Under Vespasian, 'Eirenopolis-Neronias-Sepphoris'.[21] The name 'Neronias' honours Nero, while the name 'Eirenopolis' declares Sepphoris to be a 'city of peace'[21] (Koinē Greek: Εἰρήνη, romanized: Eirēnē means tranquillity and peace,[22] and polis is a city). Pancracio Celdrán interprets this name choice as the result of the city's cultural synthesis between three elements – Jewish faith, moderated by the exposure to Greek philosophy and made more tolerant than other, more fanatic contemporary orthodox Jewish places, and a pragmatism which suited the Roman ideology.[23] Celdrán notes that the name Sepphoris was reinstated before the end of Antoninus Pius's rule.[23]

Diocaesarea

[edit]Peter Schäfer (1990), also citing G. F. Hill's conclusions based on his numismatic work done a century earlier, considers that the city's name was changed to Diocaesarea in 129/30, just prior to the Bar Kokhba revolt, in Hadrian's time.[24] This gesture was done in honour of the visiting Roman emperor and his identification with Zeus Olympias, reflected in Hadrian's efforts in building temples dedicated to the supreme Olympian god.[24] Celdrán (1995) places this name change a few decades later, during the time of Emperor Antoninus Pius (r. 138–161), when the city minted coins using this name, and interprets it as proof of the city's high degree of Hellenisation.[23] The city's coins during that period bore the inscription "ΔΙΟΚΑΙCΑΡΙΑ ΙΕΡΑ ΑCYΛΟC ΚΑΙ ΑΥΤΟΝΟΜΟC" ("of Diocaesarea, Holy City of Shelter, Autonomous").[25] Celdrán notes that the name Sepphoris was reinstated before the end of Antoninus Pius's rule.[23]

This name was not used by Jewish writers, who continued to refer to it as Zippori.[26]

History

[edit]

Canaanite and Israelite Zippori in Hebrew Bible, Mishnah, Talmud

[edit]The Hebrew Bible makes no mention of the city,[27] although in Jewish tradition it is thought to be the city Kitron mentioned in the Book of Judges (1:30 Archived 10 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine).[28][29]

According to Mishna 'Arakhin 9:6, the old fortress of Zippori was encompassed by a wall during the era of Joshua.[30]

Iron Age findings

[edit]Evidence from ceramic remains indicates the site of Sepphoris was inhabited during the Iron Age, 1,000–586 BCE.[31]

Hellenistic period; Hasmoneans

[edit]Actual occupation and building work can be verified from the 4th century BCE, with the Hellenistic period.[31]

In 104 BCE, the Judean priestly dynasty of the Hasmoneans conquered Galilee under the leadership of either Alexander Jannaeus or Aristobulus I and at this time the town may have been administered by a quarter-master, probably Jewish, and by the middle of the 1st century BCE, after the campaigns of Pompey, it fell under Roman rule in 63 BCE. Around 57 BCE, the city became one of the five synods of Roman influence in the Near East.[32][33]

Roman and Byzantine periods

[edit]It appears that Sepphoris remained predominantly Jewish through late antiquity.[8] In the centuries between the rule of Herod Antipas (4 BCE - c. 39 CE) and the end of the Byzantine era in the 630s, the city reportedly thrived as a center of learning, with a diverse, multiethnic and multireligious population of some 30,000 living in relatively peaceful coexistence.[9]

Early Roman period

[edit]The Roman client king, Herod the Great recaptured Sepphoris in 37 BCE after it had been garrisoned by the Parthian proxy, the Hasmonean Antigonus II Mattathias.[34] Herod seemingly built a royal palace-fortress that doubled as an arsenal, likely positioned within the acropolis enclosed by the city's wall.[35]

After Herod's death in 4 BCE, a rebel named Judas, son of a local bandit, Ezekias, attacked Sepphoris, then the administrative center of the Galilee, and, sacking its treasury and weapons, armed his followers in a revolt against Herodian rule.[36][6] The Roman governor in Syria, Varus is reported by Josephus – perhaps in an exaggeration, since archaeology has failed to verify traces of the conflagration – to have burnt the city down, and sold its inhabitants into slavery.[36][6] After Herod's son, Herod Antipas was made tetrarch, or governor, he proclaimed the city's new name to be Autocratoris, and rebuilt it as the "Ornament of the Galilee" (Josephus, Ant. 18.27).[37] Antipas expanded upon Herod's palace/arsenal, and built a city wall.[35] An ancient route linking Sepphoris to Legio, and further south to Sebastia (ancient Samaria), is believed to have been paved by the Romans around this time.[38] The new population was loyal to Rome.

Maurice Casey writes that, although Sepphoris during the early first century was "a very Jewish city", some of the people there did speak Greek. A lead weight dated to the first century bears an inscription in Greek with three Jewish names. Several scholars have suggested that Jesus, while working as a craftsman in Nazareth, may have travelled to Sepphoris for work purposes, possibly with his father and brothers.[39][6] Casey states that this is entirely possible, but is likewise impossible to historically verify. Jesus does not seem to have visited Sepphoris during his public ministry and none of the sayings recorded in the Synoptic Gospels mention it.[6]

The inhabitants of Sepphoris did not join the Jewish revolt against Roman rule of 66 CE. The Roman legate in Syria, Cestius Gallus, killed some 2,000 "brigands and rebels" in the area.[40] The Jerusalemite Josephus, a son of Jerusalem's priestly elite had been sent north to recruit the Galilee into the rebellion's fold, but was only partially successful. He made two attempts to capture Sepphoris, but failed to conquer it, the first time because of fierce resistance, the second because a garrison came to assist in the city's defence.[41] Around the time of the rebellion Sepphoris had a Roman theater, and in later periods, bath-houses and mosaic floors depicting human figures. Sepphoris and Jerusalem may be seen to symbolize a cultural divide between those that sought to avoid any contact with the surrounding Roman culture and those who within limits, were prepared to adopt aspects of that culture. Rejected by Sepphoris and forced to camp outside the city, Josephus went on to Jotapata, which did seem interested in the rebellion, – the Siege of Yodfat ended on 20 July 67 CE. Towns and villages that did not rebel were spared and in Galilee they were the majority.[42] Coins minted in the city at the time of the revolt carried the inscription Neronias and Eirenopolis, "City of Peace". After the revolt, coins bore depictions of laurel wreaths, palm trees, caduceuses and ears of barley, which appear on Jewish coinage albeit not exclusively.[43]

George Francis Hill and Peter Schäfer consider that the city's name was changed to Diocaesarea in 129/30, just prior to the Bar Kokhba revolt, in Hadrian's time.[24] This gesture was done in honour of the visiting Roman emperor and his identification with Zeus Olympias, reflected in Hadrian's efforts in building temples dedicated to the supreme Olympian god.[24]

Late Roman and Byzantine periods

[edit]

Following the Bar Kokhba revolt of 132–135, many Jewish refugees from devastated Judea settled there, turning it into a center of Jewish religious and spiritual life.[citation needed] Rabbi Yehuda Hanasi, the compiler of the Mishnah, a commentary on the Torah, moved to Sepphoris, along with the Sanhedrin, the highest Jewish religious court.[44] Before moving to Tiberias by 220, some Jewish academies of learning, yeshivot, were also based there. Galilee was predominantly populated by Jews from the end of the 2nd century to the 4th century CE.[45]

As late as the third-fourth centuries, Sepphoris is believed to have been settled by one of the twenty-four priestly courses, Jedayah by name, a course mentioned in relation to the town itself in both the Jerusalem Talmud (Taanit 4:5) and in the Caesarea Inscription.[46] Others, however, cast doubt about Sepphoris ever being under a "priestly oligarchy" by the third century, and that it may simply reflect a misreading of Talmudic sources.[47]

Aside from being a center of spiritual and religious studies, it developed into a busy metropolis for commerce due to its proximity to important trade routes through Galilee. Hellenistic and Jewish influences seemed blended together in daily town life while each group, Jewish, pagan and Christian, maintained its distinct identity.[48]

In the aftermath of the Jewish revolt against Constantius Gallus of 351–352, Diocaesarea, the epicenter of the revolt, was razed.[49] Philostorgius, speaking of these times, wrote: "The Jews of Diocæsarea (Sepphoris) also took up arms and invaded Palestine and the neighboring territories, with the design of shaking off the Roman yoke. On hearing of their insurrection, Gallus Caesar, who was then in Antioch, sent troops against them, defeated them, and destroyed Diocæsarea."[50] Diocaesarea was further affected by the Galilee earthquake of 363,[51] but rebuilt soon afterwards, and retained its importance in the greater Jewish community of Galilee, both socially, commercially, and spiritually.[52]

Towards the end of the 4th century, church father Epiphanius described Sepphoris as predominantly Jewish, a view strongly supported by rabbinic literature, which sheds lights on the town's sages and synagogues.[8] The town was also the center of a Christian bishopric. Three of its early bishops are known by name: Dorotheus (mentioned in 451), Marcellinus (mentioned in 518), and Cyriacus (mentioned in 536).[53][54][55] As a diocese that is no longer residential, it is listed in the Annuario Pontificio among titular sees.[56][57]

Early Muslim period

[edit]Saffuriyya

صفورية Suffurriye, Safurriya | |

|---|---|

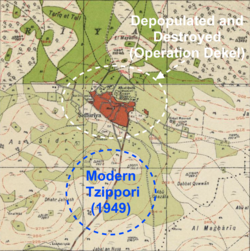

1940s Survey of Palestine map showing historical Sepphoris (Saffuriyya) in red, just prior to its depopulation in Operation Dekel, relative to the location of modern Tzippori. | |

| Palestine grid | 176/239 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Nazareth |

| Date of depopulation | 16 July 1948/January 1949[58] |

| Area | |

• Total | 55,378 dunams (55.378 km2 or 21.382 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

• Total | 4,330[60][59] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Secondary cause | Expulsion by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Tzippori; village land was also distributed between Kibbutz Sde Nahum, Kibbutz Heftziba and Kibbutz HaSolelim[58][61] Hoshaya,[62] Alon HaGalil,[62] Chanton[62] |

The fourth century saw Jewish Zippori losing its centrality as the main Jewish city of the Galilee in favour of Tiberias, and its population dwindled away.[4] With the Muslim conquest of the region, a new village rose on the ruins of ancient Zippori/Sepphoris,[4][better source needed] known by the name Saffuriya.[4] Saffuriya's main development occurred during the Mamluk period (13th–16th centuries).[4] Various Islamic dynasties controlled the site, with an interlude during the Crusades, from the 630s and up until World War I.[citation needed]

The ninth-century Islamic scholar Ya'qubi noted that Saffuriyyah was taken during the first conquest by the Arab armies in Palestine.[63] in 634.[64] Later, the city[dubious – discuss] was incorporated into the expanding Umayyad Caliphate, and al-jund coins were minted[where?] by the new rulers.[65] A stone-built aqueduct dating to the early Umayyad period (7th century CE) has been excavated.[66] Saffuriya was engaged in trade with other parts of the empire at the time; for example, cloaks made in Saffuriyya were worn by people in Medina.[67] Umayyad rule was replaced by Abbasid rule.[26]

The Crusader, Ayyubid and Mamluk periods

[edit]

At the end of the 11th century, the First Crusade invaded the region and established Crusader states, with the Kingdom of Jerusalem replacing Muslim rule over Saffuriya. During the Crusader period, Sephoris changed hands several times. The Crusaders built a fort and watchtower atop the hill overlooking the town,[68][69] and a church dedicated to Saint Anne, the mother of Mary, mother of Jesus.[70] This became one of their local bases in the kingdom, and the town was called in Old French: le Saforie or Sephoris.[69] In 1187, the field army of the Latin kingdom marched from their well-watered camp at Sephoris to be cut off and destroyed at the Battle of Hattin by the Ayyubid sultan, Saladin.

In 1255, the village and its fortifications were back in Crusader hands, as a document from that year shows it belonged to the archbishop of Nazareth,[71] but by 1259, the bishop experienced unrest among the local Muslim farmers.[72] Saffuriyyah was captured between 1263 and 1266 by the Mamluk sultan Baybars.[70]

Ottoman period

[edit]

Saffuriya (Arabic: صفورية, also transliterated Safurriya and Suffurriye), came under the rule of the Ottoman Empire after it defeated the Mamluks at the Battle of Marj Dabiq in 1516. An Ottoman firman of 1572 describes Saffuriyya as one of a group of villages within the sanjak of Safad, which was part of the Qaysi faction, and that had rebelled against the Ottoman authorities.[73] In 1596, the population was recorded as consisting of 366 families and 34 bachelors, all Muslim. Saffuriyya was larger than neighboring Nazareth but smaller than Kafr Kanna. The villagers paid a fixed tax rate of 25% on various agricultural products, including wheat, barley, olive trees, goats and beehives, in addition to a press for olive oil or grape syrup and "occasional revenues"; a total of 31,244 akçe. 3/24 of the revenuer went to a Waqf.[74] A number of important scholars came from the village during this period,[75] including the historian, poet and jurist al-Hasan al-Burini (d. 1615),[76] the qadi (head judge), al-Baq'a al-Saffuri (d. 1625) and the poet and qadi Ahmad al-Sharif (d. 1633).[75]

It is reported that in 1745 Zahir al-Umar, who grew up in the town,[77] built a fort on the hill overlooking Saffuriya.[64] A map from Napoleon's invasion of 1799 by Pierre Jacotin showed the place, named as Safoureh.[78]

In the early 19th century, the British traveller J. Buckingham noted that all the inhabitants of Saffuriya were Muslim, and that the house of St. Anna had been completely demolished.[64][79]

In the late 19th century, Saffuriyya was described as village built of stone and mud, situated along the slope of a hill. The village contained the remains of the Church of St. Anna and a square tower, said to have been built in the mid-18th century. The village had an estimated 2,500 residents, who cultivated 150 faddans (1 faddan = 100–250 dunams), on some of this land they had planted olive trees.[80]

A population list from about 1887 showed that Sepphoris had about 2,940 inhabitants; all Muslims.[81]

In 1900, an elementary school for boys was founded, and later, a school for girls.[64]

Though it lost its centrality and importance as a cultural center under the Ottomans (1517–1918) and the British Mandate (1918–1948), the village thrived agriculturally. Saffuriyya's pomegranates, olives and wheat were famous throughout the Galilee.[82]

British Mandate period

[edit]

According to the British Mandate's 1922 census of Palestine, Saffuriyeh had 2,582 inhabitants; 2,574 Muslims and 8 Christians,[83] where the Christians were all Roman Catholics.[84]

By the 1931 census the population had increased to 3,147; 3,136 Muslims and 11 Christians, in a total of 747 houses.[85] In summer of 1931, archaeologist Leroy Waterman began the first excavations at Saffuriya, digging up part of the school playground, formerly the site of the Crusader fort.[5]

A local council was established in 1923. The expenditure of the council grew from 74 Palestine pound in 1929 to 1,217 in 1944.[64]

In the 1945 statistics, the population was 4,330; 4,320 Muslims and 10 Christians,[60] and the total land area was 55,378 dunams.[59] By 1948, Saffuriya was the largest village in the Galilee both by land size and population.[86][87]

The land in the area was considered highly fertile.[87] In 1944/45 a total of 21,841 dunams of village land was used for cereals, 5,310 dunams were irrigated or used for orchards, mostly olive trees,[64][88] while 102 dunams were classified as built-up land.[89] Multiple olive oil factories were located nearby, and children attended one of two schools, divided by gender.[87]

State of Israel

[edit]

The Arab village had a history of anti-Yishuv activities and supported the Arab Liberation Army during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.[90] On 1 July 1948, the village was bombarded by Israeli aircraft.[86] On 16 July it was captured by Israeli forces along with the rest of the Lower Galilee in Operation Dekel. The villagers put up some resistance and managed to destroy several armoured cars in an ambush.[91] Following the collapse of the resistance, all but 80 of the villagers fled. Some made their way northwards toward Lebanon, finally settling there in the refugee camps of Ain al-Hilweh and Shatila and the adjacent Sabra neighborhood. Others fled south to Nazareth and the surrounding countryside. After the attack, the villagers returned but were evicted again in September 1948.[90] On 7 January 1949, 14 residents were deported and the remaining 550 were resettled in neighboring Arab villages such as 'Illut.[90]

Many settled in Nazareth in a quarter now known as the al-Safafira quarter because of the large number of Saffuriyya natives living there.[82][87] As the Israeli government considers them present absentee, they cannot go back to their old homes and have no legal recourse to recover them.[92]

The works of the poet Taha Muhammad Ali, a native of Saffuriyya expelled from the town, and their relationship to the landscape of Saffuriya before 1948, are the subject of Adina Hoffman's My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness (Yale University Press, 2009).

The area remained under martial law until the general lifting of martial law in Israel in 1966. Most of the remains of Saffuriya were removed in a late-1960s program to clear depopulated Arab villages.[93] The site of the Arab village was planted with pine trees.[86][94] By 2011, five books about the Palestinian village history had been published.[95]

On 20 February 1949, the Israeli moshav of Tzippori was founded southeast of the older village.[86] The pomegranate and olive trees were replaced with crops for cattle fodder.[96]

Saffuriya is among the Palestinian villages for which commemorative Marches of Return have taken place, typically as part of Nakba Day, such as the demonstrations organized by the Association for the Defence of the Rights of the Internally Displaced (ADRID).[97]

Archaeological park

[edit]

Roman and Byzantine city

[edit]Much of the town has been excavated, revealing Jewish homes along a main cobblestone street. Several images have been found carved into the stones of the street, including that of a menorah, and another image that resembles some ancient game reminiscent of tic-tac-toe. Stepped pools have been uncovered throughout Sepphoris, and it is generally believed that these may well have been used as Mikva'ot, Jewish ritual baths.[98][99]

Roman theatre

[edit]The Roman theatre sits on the northern slope of the hill, and is about 45 m in diameter, seating 4500. Most of it is carved into the hillside, but some parts are supported by separate stone pillars. The theatre shows evidence of ancient damage, possibly from the earthquake in 363.

Nile mosaic villa

[edit]A modern structure stands to one side of the excavations, overlooking the remains of a 5th-century public building with a large and intricate mosaic floor. Some believe the room was used for festival rituals involving a celebration of water, and possibly covering the floor in water. Drainage channels have been found in the floor, and the majority of the mosaic seems devoted to measuring the floods of the Nile, and celebrations of those floods.[100]

Dionysus mosaic villa

[edit]

A Roman villa, built around the year 200, contains an elaborate mosaic floor in what is believed to have been a triclinium. In Roman tradition, seating would have been arranged in a U-shape around the mosaic for guests to recline as they ate, drank and socialised. The mosaic features images of Dionysus, god of wine and of socialising, along with Pan and Hercules in several of the 15 panels.[100] The mosaic depicts a wine-drinking contest between Dionysus and Hercules.[101]

The most famous image is that of a young woman, possibly representing Venus, which has been dubbed the "Mona Lisa of the Galilee".[102] Smaller mosaic tesserae were used, which allowed for greater detail and a more lifelike result, as seen in the shading and blush of her cheeks.[100]

Byzantine-period synagogue

[edit]

The remains of a 5th-century synagogue have been uncovered in the lower section of the city. Measuring 20.7 meters by 8 meters wide, it was located at the edge of the town. The mosaic floor is divided into seven parts. Near the entrance is a scene showing the angels visiting Sarah. The next section shows the binding of Isaac. There is a large zodiac with the names of the months written in Hebrew. A depiction of the Greek sun god Helios sits in the middle, in his chariot. The last section shows two lions flanking a wreath, their paws resting on the head of an ox.

The mosaic shows the "tamid" sacrifice, the showbread, and the basket of first fruits form the Temple in Jerusalem. Also shown are a building facade, probably representing the Temple, incense shovels, shofars, and the seven-branched menorah from the Temple. Another section shows Aaron dressed in priestly robes preparing to offer sacrifices of oil, flour, a bull and a lamb.

An Aramaic inscription reads "May he be remembered for good Yudan son of Isaac the Priest and Paragri his daughter Amen Amen"[103]

Crusader tower

[edit]The Crusader fortress on the hill overlooking the Roman theater was built in the 12th century on the foundation of an earlier Byzantine structure. The fortress is a large square structure, 15m x15m, and approximately 10 m. high. The lower portion of the building consists of reused antique spolia, including a sarcophagus with decorative carvings. The upper part of the structure and the doorway were added by Zahir al-Umar in the 18th century. Noticeable features from the rebuilding are the rounded corners which are similar to those constructed under Zahir in the fort in Shefa-'Amr. The upper part of the building was used as a school during the reign of Abdul Hamid II in the early 1900s (late Ottoman era), and used for this purpose until 1948.[104]

Excavation history

[edit]Zippori was first excavated by Leory Waterman of University of Michigan in 1931. https://lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/publications/all-publications/leroy-waterman-and-the-university-of-michigan-excavations-at-sep.html

In 1983, James F. Strange of the University of South Florida conducted a probe of the Crusader Fortress at the top and continued excavating until 2010 on the top in Waterman's Villa, uncovering Roman Baths, and finally excavating the large administrative building at the corner of the Decumanus and Cardo. https://www.amazon.com/Excavations-Sepphoris-Reference-Library-Judaism/dp/9004126260 http://www.centuryone.org/sepphoris-site.html

Since 1990 large areas of Zippori have been excavated by an archaeological team working on behalf of the Hebrew University's Institute of Archaeology.[105]

In 2012, a survey of the site was conducted by Zidan Omar on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA).[106] In June 2018, archaeologists discovered two subterranean Byzantine-period wine presses at Tzippori National Park.[101]

See also

[edit]- Al-Burini (1556-1615), Damascus-based Ottoman Arab historian, poet, and Shafi'i jurist

- Battle of Cresson between Crusaders and Muslim troops in 1187, possibly at the Springs of Sepphoris

- Jesus Trail, 65 km (40 mi) hiking and pilgrimage route in the Galilee passing through Sepphoris

- Oldest synagogues in the world

- Shikhin (ancient Asochis), village 1.5 km north of Sepphoris, major pottery production centre in Roman Galilee

- Taha Muhammad Ali (1931–2011), Palestinian poet born in Saffuriyya

- Zodiac mosaics in ancient synagogues

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Petersen (2001), p. 270

- ^ "Tzipori National Park – Israel Nature and Parks Authority". en.parks.org.il. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ a b Palmer (1881), p. 115

- ^ a b c d e Shapira, Ran (12 December 2014). "Ancient Jewish tombstone found repurposed in 19th century Muslim mausoleum". Haaretz. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ a b Leroy Waterman (1931). "Sepphoris, Israel". The Kelsey Online. Archived from the original on 27 June 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Casey, Maurice (2010). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching. New York City, N.Y. and London, England: T & T Clark. pp. 163, 166–167. ISBN 978-0-567-64517-3.

- ^ Miller (1984), p. 132

- ^ a b c Sivan, Hagith Sara (2008). Palestine in late antiquity. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-19-928417-7.

- ^ a b Duda, Kathryn M. (1998). "Interpreting an Ancient Mosaic". Carnegie Magazine Online. Archived from the original on 14 April 2006.

- ^ The Mosaic Pavements of Roman and Byzantine Zippori

- ^ Eric Meyers, ed. (1999). Galilee, Confluence of Cultures. Winona Lake, Indiana pp. 396–7: Eisenbrauns.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Research Fellow Truman Institute Benny Morris; Benny Morris; Morris Benny (2004). Charles Tripp (ed.). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. pp. 516–7. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6. OCLC 1025810122.

- ^ Research Fellow Truman Institute Benny Morris; Benny Morris; Morris Benny (2004). Charles Tripp (ed.). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. pp. 417–. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6. OCLC 1025810122.

- ^ Nur Masalha (2014). The Zionist Bible: Biblical Precedent, Colonialism and the Erasure of Memory. Routledge. ISBN 9781317544647. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ Zippori and the Mona Lisa of the Galilee

- ^ Weiss, Zeev (2009). "The Mosaics of the Nile Festival Building at Sepphoris and the legacy of the Antiochene Tradition". Katrin Kogman-Appel, Mati Meyer (eds.). Between Judaism and Christianity: Art Historical Essays in Honor of Elisheva (Elizabeth) Revel-Neher, BRILL, pp. 9–24, p. 10.

- ^ Mariam Shahin (2005). Palestine: A Guide. Interlink Books: Northampton, Massachusetts.

- ^ Lewin, Ariel (2005). The Archaeology of Ancient Judea and Palestine. Getty Publications, p. 80.

- ^ Steve Mason (ed.) Flavius Josephus: Translation and Commentary. Judean war. Vol. 1B. 2, BRILL 2008 p. 1. Cf. Bavli, Megillah, 6, 81.

- ^ Mark A. Chancey (2002). The Myth of a Gentile Galilee. Cambridge University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780521814874.

- ^ a b c Chancey, Mark (April 2001). "The Cultural Milieu of Ancient Sepphoris". New Testament Studies. 47 (2). Cambridge University Press: 127–145 [132]. doi:10.1017/S0028688501000108. S2CID 170993934. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ Eirene at biblestudytools.com

- ^ a b c d Celdrán, Pancracio (1995). "Una ciudad en la periferia del helenismo: Sepphoris". Estudios Clásicos. 37 (107). Madrid: Sociedad Española de Estudios Clásicos: 41–50. ISSN 0014-1453. Retrieved 7 January 2022 – via Enlace Judío website.

- ^ a b c d Schäfer, Peter (1990). Philip R. Davies; Richard T. White (eds.). Hadrian's Policy in Judaea and the Bar Kokhba Revolt: A Reassessment (PDF). A&C Black. p. 281-303 [284]. ISBN 056711631X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) Also here at Google Books. - ^ Mark A. Chancey (2002). The Myth of a Gentile Galilee. Cambridge University Press. p. 82. ISBN 9780521814874.

- ^ a b Mark A. Chancey (15 December 2005). Greco-Roman Culture and the Galilee of Jesus. Cambridge University Press. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-1-139-44798-0.

- ^ Losch, Richard R. (2005). The Uttermost Part of the Earth: A Guide to Places in the Bible, William B. Eerdmans, p. ix, 209.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, Megillah 6a

- ^ Schwarz (1850), p. 173

- ^ Shivti'el, Yinon (2019). Cliff Shelters and Hiding Complexes: The Jewish Defense Methods in Galilee During the Roman Period. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN 978-3-647-54067-2 p.46

- ^ a b Fischer, Alysia (2008). Hot Pursuit: Integrating Anthropology in Search of Ancient Glass-blowers. Lexington Books, p. 40.

- ^ Josephus, J.W. 1.170

- ^ Strange, James F. (2015). "Sepphoris: The Jewel of the Galilee". Galilee in the Late Second Temple and Mishnaic Periods. Volume 2: The Archaeological Record from Cities, Towns, and Villages. Edited by David A. Fiensy and James Riley Strange (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress), 22–38, 26.

- ^ Eric M. Meyers, "Sepphoris on the Eve of the Great Revolt (67–68 C.E.): Archaeology and Josephus", in Eric M. Meyers,Galilee Through the Centuries: Confluence of Cultures, Eisenbrauns (1999), pp.109ff., pp.113–114.(Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 14.414-6).

- ^ a b Rocca, Samuel (2008). Herod's Judaea: a Mediterranean State in the Classical World. Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. p. 167. ISBN 978-3-16-149717-9.

- ^ a b Eric M. Meyers,'Sepphoris on the Eve of the Great Revolt (67–68 C.E.): Archaeology and Josephus,' in Eric M. Meyers,Galilee Through the Centuries: Confluence of Cultures, Eisenbrauns (1999), pp. 109ff., p. 114:(Josephus, Ant. 17.271-87; War 2.56–69).

- ^ Steve Mason, ed. (2008). Flavius Josephus: Translation and Commentary. Judean war. Vol. 1B. 2, BRILL, p. 138. The meaning of 'autocrator' is not clear, and may denote either autonomy or reference to a Roman emperor.

- ^ Richardson (1996), p. 133

- ^ Craig A. Evans, ed. (2014). The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus, Routledge, pp. 37, 296.

- ^ Cohen (2002), p. 195

- ^ Cohen (2002), p. 152.

- ^ Searching for Exile, Truth or Myth?, Ilan Ziv's film, screened on BBCFour, 3 November 2013

- ^ Chancey, Mark A. The Myth of a Gentile Galilee.

- ^

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Diocaesarea". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Diocaesarea". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Avian, Mordecai (2007). "Distribution Maps of Archaeological data from the Galilee". In Jürgen Zangenberg, Harold W. Attridge, Dale B. Martin (eds.), Religion, Ethnicity, and Identity in Ancient Galilee. Mohr Siebeck, pp. 115–132 (see 132).

- ^ Avi-Yonah, Michael (1964). "The Caesarea Inscription of the Twenty-Four Priestly Courses". Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies. L.A. Mayer Memorial Volume (1895–1959): 24–28. JSTOR 23614642. (Hebrew)

- ^ Stuart S. Miller (2002). "Priests, Purities, and the Jews of Galilee". In Zangenberg, Attridge, Martin (eds.), pp. 375–401 (see 379–382).

- ^ Zangenberg, Attridge, Martin, eds. (2002), pp. 9, 438.

- ^ Bernard Lazare and Robert Wistrich (1995). Antisemitism: Its History and Causes. University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 080327954X.

- ^ Sozomen; Philostorgius (1855). The Ecclesiastical History of Sozomen and The Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius. Translated by Edward Walford. London: Henry G. Bohn. p. 153 (Book IV, chapter VII). OCLC 224145372.

- ^ "Israel Seismic Activity Since The Times Of Jesus". The Urantia Book Fellowship. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Knight, Kevin. "Diocaesarea". Catholic Encyclopedia. Kevin Knight. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae, Leipzig 1931, p. 454

- ^ Konrad Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica Medii Aevi, vol. 4, p. 175

- ^ Raymond Janin, v. 2. Diocésarée, in Dictionnaire d'Histoire et de Géographie ecclésiastiques, vol. XIV, Paris 1960, coll. 493.494

- ^ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013, ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 881

- ^ Names of its titular bishop from the 18th to the 20th century can be found at GCatholic.com

- ^ a b Morris (2004), p. xvii, village #139

- ^ a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April 1945. Quoted in Hadawi (1970), p. 63

- ^ a b Department of Statistics (1945), p. 8

- ^ Morris (2004), pp. 516-517

- ^ a b c Khalidi (1992), p. 352

- ^ le Strange (1890), p.32

- ^ a b c d e f Khalidi (1992), p. 351.

- ^ Aubin (2000), p. 12 Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Berger and Barzilai (2013), Nahal Zippori 23

- ^ Crone (2004), p. 102

- ^ Conder and Kitchener (1881), SWP I, pp. 335-338

- ^ a b Pringle (1997), p. 92

- ^ a b Pringle (1998), pp. 209-210

- ^ Röhricht (1893), RRH, pp. 326-327, No 1242; cited in Pringle (1998), p. 210

- ^ Röhricht (1893), RRH, p. 335, No 1280; cited in Pringle (1998), p. 210

- ^ Heydn (1960), pp. 83–84. Cited in Petersen (2001), p. 269

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah (1977), p. 188

- ^ a b Khalidi (1992), pp. 350–353

- ^ Brockelmann (1960), p. 1333

- ^ Pappe, Illan (2010) The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian Dynasty. The Husaynis 1700–1968. Saqi, ISBN 978-0-86356-460-4. p. 35.

- ^ Karmon (1960), p. 166 Archived 22 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Buckingham (1821), pp. 90-91

- ^ Conder and Kitchener (1881), SWP I, pp. 279 −280. Quoted in Khalidi (1992), p. 351.

- ^ Schumacher (1888), p. 182

- ^ a b Laurie King-Irani (November 2000). "Land, Identity and the Limits of Resistance in the Galilee". Middle East Report. 216 (216): 40–44. doi:10.2307/1520216. JSTOR 1520216.

- ^ Barron (1923), Table XI, Sub-district of Nazareth, p. 38

- ^ Barron (1923), Table XVI, p. 51

- ^ Mills (1932), p. 76

- ^ a b c d IIED, 1994, p. 95

- ^ a b c d Matar, Dina (2011). What it Means to be Palestinian: Stories of Palestinian Peoplehood. I.B.Tauris. pp. 42, incl. fn 54. doi:10.5040/9780755610891. ISBN 978-0-7556-1460-8.

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April 1945. Quoted in Hadawi (1970), p. 110

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April 1945. Quoted in Hadawi (1970), p. 160

- ^ a b c Morris (2004), pp. 417, 418 516–517

- ^ O'Ballance, Edgar (1956) The Arab-Israeli War. 1948. Faber & Faber, London. p. 157.

- ^ Kacowicz and Lutomski (2007), p. 140

- ^ Aron Shai (2006). "The fate of abandoned Arab villages in Israel, 1965–1969". History & Memory. 18 (2): 86–106. doi:10.2979/his.2006.18.2.86. S2CID 159773082.

- ^ Zochrot. "Zochrot - Safuriyya". Zochrot - Safuriyya. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ Davis (2011), p. 30

- ^ Benvenisti (2002), p. 216

- ^ Charif, Maher. "Meanings of the Nakba". Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question – palquest. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ Stuart S. Millar, 'Review Essay: Roman Imperialism, Jewish Self-Definition, and Rabbinic Society,' AJS 31:2 (2007), 329–362 DOI: 10.1017/S0364009407000566 pp.340-341, with notes 24,25.

- ^ Bar-Am, Aviva (25 January 2010). "Ancient Tzipori". Jerusalem Post.

- ^ a b c Tzipori National Park pamphlet (PDF) (in Hebrew), archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2011, retrieved 28 August 2011

- ^ a b Unique Byzantine-era winepresses unearthed in roofed water cistern in Tzippori

- ^ The surprises of Sepphoris

- ^ Jewish Heritage Report Vol. I, Nos. 3–4 / Winter 1997–98 Sepphoris Mosaic Symposium Held in Conjunction with Sepphoris Mosaic Exhibition Archived 28 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine by Leslie Bussis Tait

- ^ Petersen (2001), pp. 269-270

- ^ Israel Antiquities Authority, Excavators and Excavations Permit for Year 2010, Survey Permit # G-38

- ^ Israel Antiquities Authority, Excavators and Excavations Permit for Year 2012, Survey Permit # A-6675

Bibliography

[edit]- Aubin, Melissa M. (2000). The Changing Landscape of Byzantine Sepphoris (PDF). ASOR Publications. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 June 2003.

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Barzilai, Omry (18 November 2010). 'En Zippori (Report). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

- Barzilai, Omry; et al. (19 August 2013). Nahal Zippori, the Eshkol Reservoir–Somekh Reservoir Pipeline (Report). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

- Benveniśtî, M. (2002). Sacred landscape: the buried history of the Holy Land since 1948 (Illustrated ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 9780520234222.

- Berger, Uri; Barzilai, Omry (28 December 2013). "Nahal Zippori 23" (125). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Brockelmann, C. (1960). "Al-Burini". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 1333. OCLC 495469456.

- Buckingham, J.S. (1821). Travels in Palestine through the countries of Bashan and Gilead, east of the River Jordan, including a visit to the cities of Geraza and Gamala in the Decapolis. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown.

- Chancey, Mark A. (2005). Greco-Roman culture and the Galilee of Jesus (Illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521846479.

- Cohen, S.J.D. (2002). Josephus in Galilee and Rome: His Vita and Development As a Historian. BRILL. ISBN 978-0391041585.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Crone, P. (2004). Meccan trade and the rise of Islam. Gorgias Press. ISBN 9781593331023.[permanent dead link]

- Davis, Rochelle (2011). Palestinian Village Histories: Geographies of the Displaced. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7313-3.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Guérin, V (1880). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 3: Galilee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- (IIED), International Institute for Environment & Development (1994). Evictions – 7010iied. IIED. ISBN 9781843690825.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Heyd, Uriel (1960): Ottoman Documents on Palestine, 1552–1615, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Cited in Petersen (2002)

- Hütteroth, W.-D.; Abdulfattah, K. (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-920405-41-4.

- Kacowicz, Arie Marcelo; Lutomski, Pawel (2007). Population resettlement in international conflicts: a comparative study (Illustrated ed.). Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739116074.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 978-0-88728-224-9.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Miller, Stuart S. (1984). Studies in the History and Traditions of Sepphoris. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004069268.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Pococke, R. (1745). A description of the East, and some other countries. Vol. 2. London: Printed for the author, by W. Bowyer.

- Porat, Leea (8 May 2005). "El-En Zippori" (117). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Pringle, D. (1997). Secular buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: an archaeological Gazetter. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521-46010-7.

- Pringle, D. (1998). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: L-Z (excluding Tyre). Vol. II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39037-0.

- Richardson, Peter (1996). Herod: king of the Jews and friend of the Romans (Illustrated ed.). University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9781570031366.

- Rowan, Yorke M.; Baram, U. (2004). Marketing heritage: archaeology and the consumption of the past (Illustrated ed.). Rowman Altamira. ISBN 9780759103429.

- Röhricht, R. (1893). (RRH) Regesta regni Hierosolymitani (MXCVII-MCCXCI) (in Latin). Berlin: Libraria Academica Wageriana.

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly Statement. 20. Palestine Exploration Fund: 169–191.

- Schwarz, Joseph (1850). A Descriptive Geography and Brief Historical Sketch of Palestine. Translated by Isaac Leeser. Macmillan.

External links

[edit]- Tzippori excavation project Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Saffuriyya Palestine Remembered

- Safuriyya, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 5: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Saffuryeh, from Dr. Moslih Kanaaneh

- Zippori Archived 27 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine Hillel International

- Zippori Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (Accessed 9 February 2005.)

- Zippori National Park, official brochure with site map. (Accessed 27 December 2019.)

- Photos of Sepphoris from the Manar al-Athar photo archive

- Jezreel Valley Regional Council

- Populated places established in the 5th millennium BC

- Ancient Israel and Judah

- Archaeological sites in Israel

- Crusader castles

- Castles and fortifications of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

- Castles in Israel

- National parks of Israel

- Catholic titular sees in Asia

- District of Nazareth

- Arab villages depopulated during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

- Mosaics

- Talmud places

- Populated places in Northern District (Israel)

- Roman towns and cities in Israel

- Ancient Jewish settlements of Galilee

- Church buildings in the Kingdom of Jerusalem

- Israeli mosaics

- Mary, mother of Jesus

- Herod Antipas