Ted Stevens

Ted Stevens | |

|---|---|

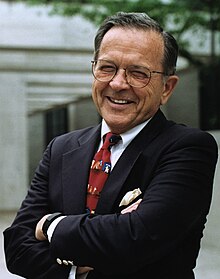

Official portrait, 1997 | |

| United States Senator from Alaska | |

| In office December 24, 1968 – January 3, 2009 | |

| Preceded by | Bob Bartlett |

| Succeeded by | Mark Begich |

| President pro tempore of the United States Senate | |

| In office January 3, 2003 – January 3, 2007 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Byrd |

| Succeeded by | Robert Byrd |

| President pro tempore emeritus of the United States Senate | |

| In office January 3, 2007 – January 3, 2009 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Byrd |

| Succeeded by | Patrick Leahy (2015) |

| Senate Majority Whip | |

| In office January 3, 1981 – January 3, 1985 | |

| Leader | Howard Baker |

| Preceded by | Alan Cranston |

| Succeeded by | Alan Simpson |

| Senate Minority Leader | |

| Acting November 1, 1979 – March 5, 1980 | |

| Preceded by | Howard Baker |

| Succeeded by | Howard Baker |

| Senate Minority Whip | |

| In office January 3, 1977 – January 3, 1981 | |

| Leader | Howard Baker |

| Preceded by | Robert P. Griffin |

| Succeeded by | Alan Cranston |

| Member of the Alaska House of Representatives from the 8th district | |

| In office January 3, 1964 – January 3, 1968 | |

| Preceded by | Multi-member district |

| Succeeded by | Multi-member district |

| Chief Legal Officer of the United States Department of the Interior[2] | |

| In office September 15, 1960 – January 20, 1961 | |

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Secretary | Fred Seaton |

| Preceded by | George W. Abbott |

| United States Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Legislation | |

| In office June 1, 1956 – September 15, 1960 | |

| President | Dwight Eisenhower |

| Secretary | Douglas McKay Fred Seaton |

| United States Attorney for the Fourth Division of Alaska Territory | |

| In office August 31, 1953 – June 1, 1956 Acting: August 31, 1953 – March 30, 1954 | |

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Robert McNealy |

| Succeeded by | George Yeager |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Theodore Fulton Stevens November 18, 1923 Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died | August 9, 2010 (aged 86) Dillingham Census Area, Alaska, U.S. |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 6, including Ben |

| Education | |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1943–1946 |

| Rank | First lieutenant |

| Unit | United States Army Air Forces |

| Battles/wars | World War II, The Hump |

Theodore Fulton Stevens Sr. (November 18, 1923 – August 9, 2010)[1][2] was an American politician and lawyer who served as a U.S. Senator from Alaska from 1968 to 2009.

He was the longest-serving Republican Senator in history at the time he left office. Stevens was the president pro tempore of the United States Senate in the 108th and 109th Congresses from 2003 to 2007, and was the third U.S. Senator to hold the title of president pro tempore emeritus. He was previously Solicitor of the Interior Department from 1960 to 1961.[3][4][5] Stevens has been described as one of the most powerful members of Congress and as the most powerful member of Congress from the Northwestern United States.[6][7][8]

Stevens served for six decades in the American public sector, beginning with his service as a pilot in World War II. In 1952, his law career took him to Fairbanks, Alaska, where he was appointed U.S. Attorney the following year by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. In 1956, he returned to Washington, D. C., to work in the Eisenhower Interior Department, eventually rising to become Senior Counsel and Solicitor of the Department of the Interior, where he played an important role as an executive official in bringing about and lobbying for statehood for Alaska, as well as forming the Arctic National Wildlife Range.

After unsuccessfully running to represent Alaska in the United States Senate, Stevens was elected to the Alaska House of Representatives in 1964 and became House majority leader in his second term. In 1968, Stevens again unsuccessfully ran for Senate, but he was appointed to Bob Bartlett's vacant seat after Bartlett's death later that year. As a senator, Stevens played key roles in legislation that shaped Alaska's economic and social development,[9] with Alaskans describing Stevens as "the state's largest industry" and nicknaming the federal money he brought in "Stevens money".[10] This legislation included the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act, Title IX,[11] gaining him the nickname "The Father of Title IX",[12] the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, and the Magnuson–Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act. He was also known for his sponsorship of the Amateur Sports Act of 1978,[13] which established the United States Olympic & Paralympic Committee.

In 2008, Stevens was embroiled in a federal corruption trial as he ran for re-election to the Senate. He was initially found guilty, and, eight days later, he was narrowly defeated by Anchorage Mayor Mark Begich.[14] Stevens was the longest-serving U.S. Senator to have ever lost a bid for re-election. However, when a Justice Department probe found evidence of gross prosecutorial misconduct,[15] U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder asked the court to vacate the conviction and dismiss the underlying indictment,[16] and Judge Emmet G. Sullivan granted the motion.[17]: 772 Stevens died on August 9, 2010, near Dillingham, Alaska, when a de Havilland Canada DHC-3 Otter he and several others were flying in crashed en route to a private fishing lodge.[18]

Early life and career

[edit]Childhood and youth

[edit]

Stevens was born November 18, 1923, in Indianapolis, Indiana, the third of four children,[19][20] in a small cottage built by his paternal grandfather after the marriage of his parents, Gertrude S. Chancellor and George A. Stevens. The family later lived in Chicago, where George was an accountant before losing his job during the Great Depression.[20][21]: 220 Around this time, when Ted Stevens was six years old, his parents divorced, and Stevens and his three siblings moved back to Indianapolis so they could reside with their paternal grandparents, followed shortly thereafter by their father, who developed problems with his eyes which eventually blinded him. Stevens's mother moved to California and sent for Stevens's siblings as she could afford to, but Stevens stayed in Indianapolis helping to care for his father and a mentally disabled cousin, Patricia Acker, who also lived with the family. The only adult in the household with a job was Stevens's grandfather. Stevens helped to support the family by working as a newsboy, and would later remember selling many newspapers on March 1, 1932, when newspaper headlines blared the news of the Lindbergh kidnapping.[20]

In 1934 Stevens's grandfather punctured a lung in a fall down a tall flight of stairs, contracted pneumonia, and died.[20] Stevens's father, George, died in 1957 in Tulsa, Oklahoma, of lung cancer.[21]: 220 Stevens and his cousin Patricia moved to Manhattan Beach, California in 1938, by which time both of Stevens's grandparents had died,[5] to live with Patricia's mother, Gladys Swindells.[20] Stevens attended Redondo Union High School, participating in extracurricular activities including working on the school newspaper and becoming a member of a student theater group affiliated with the YMCA, and, during his senior year, the Lettermen's Society. Stevens also worked at jobs before and after school,[21]: 220 but still had time for surfing with his friend Russell Green, the son of the Signal Gas and Oil Company's president, who remained a close friend throughout Stevens's life.[20][10]

Military service

[edit]

After he graduated from Redondo Union High School in 1942,[22] Stevens enrolled at Oregon State University to study engineering,[21]: 221 attending for a semester.[20] With World War II in progress, Stevens attempted to join the Navy and serve in naval aviation, but failed the vision exam. He corrected his vision through a course of prescribed eye exercises, and in 1943 he was accepted into an Army Air Force Air Cadet program at Montana State College.[20][21]: 221 Stevens said that, after scoring near the top of his class on an aptitude test for flight training, he was transferred from the program to preflight training in Santa Ana, California, and he received his wings early in 1944.[20]

Stevens served in the China-Burma-India theater with the Fourteenth Air Force Transport Section, which supported the "Flying Tigers", from 1944 to 1945. He and other pilots in the transport section flew C-46 and C-47 transport planes, often without escort, mostly in support of Chinese units fighting the Japanese.[20] Stevens received the Distinguished Flying Cross for flying behind enemy lines, the Air Medal, and the Yuan Hai Medal awarded by the Chinese Nationalist government.[20] He was discharged from the Army Air Forces in March 1946.[20]

Higher education and law school

[edit]After the war, Stevens attended the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), where he earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in political science in 1947.[20] While at UCLA, he was a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity (Theta Rho chapter).[23] He applied to law school at Stanford and the University of Michigan, but on the advice of his friend Russell Green's father to "look East", he applied to Harvard Law School, which he ended up attending. Stevens's education was partly financed by the G.I. Bill; he made up the difference by selling his blood, borrowing money from an uncle, and working several jobs including one as a bartender in Boston.[20] During the summer of 1949, Stevens was a research assistant in the office of the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of California (now the Central District of California).[24][21]: 222

While at Harvard, Stevens wrote a paper on maritime law that received honorable mention for the Addison Brown prize, a Harvard Law School award for the best student-penned essay related to private international law or maritime law.[24] The essay later became a Harvard Law Review article,[25] and, 45 years later, Justice Jay Rabinowitz of the Alaska Supreme Court praised Stevens's scholarship, telling the Anchorage Daily News that the high court had issued a recent opinion citing the article.[20] Stevens graduated from Harvard Law School in 1950.[20]

Early legal career

[edit]After graduating, Stevens went to work in the Washington, D.C., law offices of Northcutt Ely.[24][26] Twenty years earlier, Ely had been executive assistant to Secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur during the Hoover administration,[27] and, by 1950, he headed a prominent law firm specializing in natural resources issues.[26] One of Ely's clients, Emil Usibelli, founder of the Usibelli Coal Mine in Healy, Alaska,[28] was trying to sell coal to the military, and Stevens was assigned to handle his legal affairs.[26]

Marriage and family

[edit]Early in 1952, Stevens married Ann Mary Cherrington, a Democrat and the adopted daughter of University of Denver Chancellor Ben Mark Cherrington. She had graduated from Reed College in Portland, Oregon, and during Truman's administration had worked for the State Department.[26]

On December 4, 1978, the crash of a Learjet 25C on approach at Anchorage International Airport killed five of the seven aboard; Stevens survived, suffering a concussion and broken ribs,[29] but his wife, Ann, did not. Stevens would later state in an interview with the Anchorage Times "I can't remember anything that happened." Smiling, he added, "I'm still here. It must be my Scots blood."[30][31][32] The building which houses the Alaska chapter of the American Red Cross at 235 East Eighth Avenue in Anchorage is named in her memory; likewise a reading room at the Loussac Library.[33]

Stevens and Ann had three sons (Ben, Walter, and Ted) and two daughters (Susan and Elizabeth).[34] Democratic Governor Tony Knowles appointed Ben to the Alaska Senate in 2001, where he served as the president of the state senate until the fall of 2006.

Ted Stevens remarried in 1980. He and his second wife, Catherine, had a daughter, Lily.

Stevens's last Alaska home was in Girdwood, a ski resort community near the southern edge of Anchorage's city limits, about forty miles (65 km) by road from downtown. The home was the subject of media attention after it was raided by FBI & IRS agents in 2007.[35]

Prostate cancer

[edit]Stevens was a survivor of prostate cancer and had publicly disclosed his cancer.[36][37] He was nominated for the first Golden Glove Awards for Prostate Cancer by the National Prostate Cancer Coalition (NPCC). He advocated the creation of the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program for Prostate Cancer at the Department of Defense, which has funded nearly $750 million for prostate cancer research.[38] Stevens was a recipient of the Presidential Citation by the American Urological Association for significantly promoting urology causes.[39]

Early Alaska career

[edit]In 1952, while still working for Northcutt Ely, Stevens volunteered for the presidential campaign of Dwight D. Eisenhower, writing position papers for the campaign on western water law and lands. By the time Eisenhower won the election that November, Stevens had acquired contacts who told him, "We want you to come over to Interior." Stevens left his job with Ely, but a job in the Eisenhower administration didn't come through[26] as a result of a temporary hiring freeze instituted by Eisenhower in an effort to reduce spending.[21]: 222

Instead, Stevens was offered a job with the Fairbanks, Alaska, law firm of Charles Clasby, Emil Usibelli's Alaska attorney whose firm (Collins & Clasby) had just lost one of its attorneys.[21]: 222 [26] Stevens and his wife had met and liked both Usibelli and Clasby, and decided to make the move.[26] Loading up their 1947 Buick[21]: 223 and traveling on a $600 loan from Clasby, they drove across country from Washington, D.C., and up the Alaska Highway in the dead of winter, arriving in Fairbanks in February 1953. Stevens later recalled kidding Governor Walter Hickel about the loan. "He likes to say that he came to Alaska with 38 cents in his pocket," he said of Hickel. "I came $600 in debt."[26] Ann Stevens recalled in 1968 that they made the move to Alaska "on a six-month trial basis".[21]: 223

In Fairbanks, Stevens made contacts within the city's Republican party division. He befriended conservative newspaper publisher C.W. Snedden, who had purchased the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner in 1950. Snedden's wife, Helen, later recalled that Snedden and Stevens were "like father and son". However, she would add in 1994 that "The only problem Ted had was that he had a temper," crediting her husband with helping to steady Stevens like you would do with a son, and with teaching Stevens the art of diplomacy.[26]

U.S. Attorney

[edit]Nomination

[edit]Stevens had been with Collins & Clasby for six months when Robert J. McNealy, a Democrat appointed as U.S. Attorney for Fairbanks during the Truman administration,[26] informed U.S. District Judge Harry Pratt he would be resigning effective August 15, 1953,[21]: 224 having already delayed his resignation by several months at the request of Justice Department officials newly appointed by Eisenhower. The latter had asked McNealy to delay his resignation until Eisenhower could appoint a replacement.[21]: 223 Despite Stevens's short tenure as an Alaska resident and his relative lack of trial or criminal law experience, Pratt asked Stevens to serve in the position until Eisenhower acted.[21]: 224 Stevens agreed. "I said, 'Sure, I'd like to do that,'" Stevens recalled years later. "Clasby said to me, 'It's not going to pay you as much money', but, 'if you want to do it, that's your business.' He was very pissed that I decided to go."[26] Most members of the Fairbanks Bar Association voiced their disapproval of the appointment of a newcomer, and members in attendance at the association's meeting that December voted to instead support Carl Messenger for the permanent appointment, an endorsement seconded by the Alaska Republican Party Committee for the Fairbanks-area judicial division.[21]: 224 However, Stevens was favored by Attorney General Herbert Brownell, Senator William F. Knowland of California, and the Republican National Committee,[21]: 224 (Alaska itself had no Senators at this time, as it was still a territory). Eisenhower sent Stevens's nomination to the U.S. Senate on February 25, 1954,[3][21]: 225 and the Senate confirmed him on March 30.[26]

Career as U.S. Attorney

[edit]Stevens soon gained a reputation as an active prosecutor who vigorously prosecuted violations of both federal and territorial liquor, drug, and prostitution laws,[26] characterized by Fairbanks area homesteader Niilo Koponen (who later served in the Alaska State House of Representatives from 1982 to 1991) as "this rough tough shorty of a district attorney who was going to crush crime".[21]: 225 Stevens sometimes accompanied U.S. Marshals on raids. As recounted years later by Justice Jay Rabinowitz, "U.S. marshals went in with Tommy guns and Ted led the charge, smoking a stogie and with six guns on his hips."[26] However, Stevens himself said the colorful stories spread about him as a pistol-packing D.A. were greatly exaggerated, and recalled only one incident when he carried a gun: on a vice raid to the town of Big Delta about 75 miles (121 km) southeast of Fairbanks, he carried a holstered gun on a marshal's suggestion.[26]

Stevens also became known for his explosive temper, which was focused particularly on a criminal defense lawyer named Warren A. Taylor[26] who would later go on to become the Alaska Legislature's first Speaker of the House in the First Alaska State Legislature.[40] "Ted would get red in the face, blow up and stalk out of the courtroom," a former court clerk later recalled of Stevens's relationship with Taylor.[26] Later on, a former colleague of Stevens would "cringe at remembering hearing Stevens through the wall of their Anchorage law office berating clients." Stevens's wife, Ann, would make her husband read self-help books to try and calm him down, although this effort was to no avail. As one observer remembered: "He would lose his temper about the dumbest things. Even when you would agree with him, he got mad at you for agreeing with him."[5]

In 1956, in a trial which received national headlines, Stevens prosecuted Jack Marler; a former Internal Revenue Service agent who had been indicted for failing to file tax returns. Marler's first trial, which was handled by a different prosecutor, had ended in a deadlocked jury and a mistrial. For the second trial, Stevens was up against Edgar Paul Boyko, a flamboyant Anchorage attorney who built his defense of Marler on the theory of no taxation without representation, citing the Territory of Alaska's lack of representation in the U.S. Congress. As recalled by Boyko, his closing argument to the jury was a rabble-rousing appeal for the jury to "strike a blow for Alaskan freedom", claiming that "this case was the jury's chance to move Alaska toward statehood." Boyko remembered that "Ted had done a hell of a job in the case," but Boyko's tactics paid off, and Marler was acquitted on April 3, 1956. Following the acquittal, Stevens issued a statement saying, "I don't believe the jury's verdict is an expression of resistance to taxes or law enforcement or the start of a Boston Tea Party." Stevens then followed "I do believe, however, that the decision will be a blow to the hopes for Alaska statehood."[26]

Department of the Interior

[edit]Alaska statehood

[edit]

In March 1956, Stevens's friend Elmer Bennett, legislative counsel in the Department of the Interior, was promoted by Secretary of the Interior Douglas McKay to the Secretary's office. Bennett successfully lobbied McKay to replace him in his old job with Stevens, and Stevens returned to Washington, D.C., to take up the position.[21]: 226 By the time he arrived in June 1956, McKay had resigned in order to run for the U.S. Senate from his home state of Oregon, and Fred Andrew Seaton had been appointed to replace him.[21]: 226 [41] Seaton, a newspaper publisher from Nebraska,[21]: 226 was a close friend of Fairbanks Daily News-Miner publisher C.W. Snedden, who was in addition friends with Stevens, and in common with Snedden was an advocate of Alaska statehood,[41] unlike McKay, who had been lukewarm in his support.[21]: 226 Upon his appointment, Seaton asked Snedden if he knew anyone from Alaska who could come down to Washington, D.C. to work for Alaska statehood; Snedden replied that the man he needed (Stevens) was already there working in the Department of the Interior.[41] The fight for Alaska statehood became Stevens's principal work at Interior. "He did all the work on statehood," Roger Ernst, the then Assistant Secretary of Interior for Public Land Management, later said of Stevens. "He wrote 90 percent of all the speeches; Statehood was his main project."[41] A sign on Stevens's door proclaimed his office as "Alaskan Headquarters", and Stevens became known at the Department of the Interior as "Mr. Alaska".[21]: 226

Efforts to make Alaska a state had been going on since 1943, and had nearly come to fruition during the Truman administration in 1950 when a statehood bill passed in the U.S. House of Representatives, only to die in the Senate.[41] The national Republican Party opposed statehood for Alaska, in part out of fear that Alaska would, upon statehood, elect Democrats to the U.S. Congress, while the Southern Democrats opposed statehood, believing that the addition of 2 new pro-civil rights Senators would jeopardize the Solid South's control on Congressional law.[41] At the time Stevens arrived in Washington, D.C., to take up his new job, a constitutional convention to write an Alaska constitution had just been concluded on the campus of the University of Alaska in Fairbanks.[42] The 55 delegates also elected three unofficial representatives (all Democrats) as unofficial Shadow congressmen: Ernest Gruening and William Egan as Shadow U.S. Senators and Ralph Rivers as Shadow at-large U.S. representative.[41]

President Eisenhower, a Republican, regarded Alaska as too large in area and with a population density too low to be economically self-sufficient as a state, and furthermore saw statehood as an obstacle to effective defense of Alaska should the Soviet Union seek to invade it.[41] Eisenhower was especially worried about the sparsely populated areas of northern and western Alaska. In March 1954, he had reportedly "drawn a line on a map" indicating his opinion of the portions of Alaska which he felt ought to remain in federal hands even if Alaska were granted statehood.[41]

Seaton and Stevens worked with Gen. Nathan Twining, the incumbent Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who himself had previously served in Alaska; and Jack L. Stempler, a top Defense Department attorney, to create a compromise that would address Eisenhower's concerns. Much of their work was conducted in a hospital room at Walter Reed Army Hospital, where Interior Secretary Seaton was receiving treatment for reoccurring health issues with his back.[41] Their work concentrated on refining the line on the map that Eisenhower had drawn in 1954, one which became known as the PYK Line after three rivers (the Porcupine, Yukon, and Kuskokwim) whose courses defined much of the line.[41] The PYK Line was the basis for Section 10 of the Alaska Statehood Act, which Stevens wrote.[41] Under Section 10, the land north and west of the PYK Line – which included the entirety of Alaska's North Slope, the Seward Peninsula, most of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, the western portions of the Alaska Peninsula, and the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands – would be part of the new state, but the president would be granted emergency powers to establish special national defense withdrawals in those areas if deemed necessary.[43][44][45] "It's still in the law but it's never been exercised," Stevens later recollected. "Now that the problem with Russia is gone, it's surplusage. But it is a special law that only applies to Alaska."[41]

Stevens, illegally, also took part in lobbying for the statehood bill,[41] working closely with the Alaska Statehood Committee from his office at Interior.[41] Stevens hired Marilyn Atwood,[41] daughter of Anchorage Times publisher Robert Atwood,[41] who was chairman of the Alaska Statehood Committee,[46] to work with him in the Interior Department. "We were violating the law," Stevens told a researcher in an October 1977 oral history interview for the Eisenhower Library. Stevens explained in the interview that they were violating a long-standing statute against lobbying from the executive branch. "We more or less masterminded the House and Senate attack from the executive branch."[41] Stevens and the younger Atwood created file cards on Congressmen based on their backgrounds, identity and religious beliefs, as he later recalled in the 1977 interview. "We'd assigned these Alaskans to go talk to individual members of the Senate and split them down on the basis of people that had something in common with them."[41] The lobbying campaign extended to presidential press conferences. "We set Ike (Eisenhower) up quite often at press conferences by planting questions about Alaska statehood," Stevens said in the 1977 interview. "We never let a press conference go by without getting someone to try to ask him about statehood."[41] Newspapers were also targeted, according to Stevens. "We planted editorials in weeklies and dailies and newspapers in the district of people we thought were opposed to us or states where they were opposed to us." Stevens then added "...Suddenly they were thinking twice about opposing us."[41]

The Alaska Statehood Act became law with Eisenhower's signature on July 7, 1958,[43] and Alaska formally was admitted to statehood on January 3, 1959, when Eisenhower signed the Alaska Statehood Proclamation.[47]

Solicitor of Interior

[edit]On September 15, 1960, George W. Abbott resigned as Solicitor of the Interior to become Assistant Secretary, and Stevens became Solicitor. He stayed in this office until the Eisenhower administration left office on January 20, 1961.[48] In his position as the highest attorney in the Interior Department, he authored the order that created the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in 1960.[6][49][50]

Return to Alaska and service in the Alaska House of Representatives

[edit]After returning to Alaska, Stevens managed Richard Nixon's 1960 campaign in Alaska. Nixon lost the election narrowly to John F. Kennedy, but won Alaska, which was unexpected due to Alaska's Democratic lean.[51] Shortly after, Stevens founded Stevens & Savage, a law firm in Anchorage. Stevens was then joined by H. Russel Holland, who later became a federal judge on the U.S. District Court for the District of Alaska, and the firm's name changed to Stevens, Savage & Holland.[52] Stevens became a member of Operation Rampart, a group in favor of building the Rampart Dam, a hydroelectric project on the Yukon River.[53] Elected to the Alaska House of Representatives in 1964, he became House Majority Leader in his second term.[54] In this position, he helped push through the repeal of a law that the Governor must appoint a U.S. Senator of the same party as their predecessor when filling a Senate vacancy, benefitting from this law change the next year when Bob Bartlett died.[55]

U.S. Senator

[edit]Service

[edit]

Stevens's service as a United States Senator was, at first, marked with instability and controversy. Mike Gravel stated that he had no issue with Stevens being the senior senator, because he was seven years Stevens's junior, and Stevens had been in public service for longer than he had.[56] Even after losing the 1968 Republican primary, Stevens embarked on a state-wide campaign for the Republican nominee, Elmer Rasmuson, attacking Gravel on his time as Speaker of the Alaska House of Representatives. When they were being sworn in together in 1969, Stevens approached Gravel and apologized, asking if they could "let political bygones be bygones", so that they could work together. However, Gravel replied "I don't want to be your friend, Ted. I didn't appreciate you going around the state and lying about me." Gravel and Stevens never recovered, with Gravel later recalling "We'd talk about things. I'd joke with him. He's got a sense of humor." However, Gravel would add "He didn't use it on me unless I was the butt of it."[5]

During the inaugural meeting of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs during the 91st United States Congress, Stevens commandeered the meeting, booming: "The first priority has to be settlement of Alaska Native land claims. This committee hadn't had the guts to do it at statehood." By the end of the meeting, Stevens and Gravel had ended up in a shouting match, constantly interrupting and disrespecting each other, boiling out into the hallway, fists raised, giving statements to the press in a makeshift conference before Chairman Henry "Scoop" Jackson interrupted and broke up the fight.[5] In one incident, Stevens began lecturing Jackson, the chairman. Jackson put his foot down, stating "Now just a minute. You're new here and I want to tell you how these things are handled." Ed Weinberg would recall that Jackson treated Ted Stevens like he was a rebellious schoolboy and, as such, would make him "sit in the corner with a dunce cap on." "Jackson wasn't about to let Ted Stevens take over the hearings and the framing of this legislation."[5]

Following the 1974 campaign, where Stevens begrudgingly campaigned for the Republican nominee, leading John Birch Society member C.R. Lewis, Stevens again tried to put their rivalry aside, sending a letter inviting Gravel and his wife to a "nice dinner" with him and his wife. However, Gravel turned it down, later recalling he showed Stevens that he "didn't want to socialize with him." Gravel felt Stevens did not behave appropriately during the campaign, adding "I wanted nothing to do with him socially."[57]

On October 13, 1978, the last day of the second sitting of the 95th Congress, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, an act to conserve around a third of Alaska as 'America's last huge, untouched wilderness', an act which Stevens championed after providing a compromise with Mo Udall, was killed by Gravel. One theory why was that Gravel killed the bill in an attempt to spite Stevens, but it is more widely accepted that Gravel had killed the bill as part of his 1980 re-election campaign. The day before, Gravel had written to Stevens that he 'supported Stevens' and was reconsidering his opposition of any attempt of a compromise.[58][57] On the day, the bill was granted an extension for a year by the House, but when the Senate debated the extension, Stevens did not present Gravel's objections to the Senate. In response, Gravel stood up and killed the extension, stating that astounded him how members of Congress could "meet so much on a subject" that "affected someone else's state." Gravel would then add that he "had been willing to rise above this and work on the compromise", even though he believed the bill "...was anathema to what I thought was right and in the best interests of Alaska..."[57]

Democratic New Hampshire Senator John A. Durkin rose. "The whole chamber knows what the senator is up to. He is out to torpedo this bill!" Gravel rebutted "I will not admit that!", continuing to speak until Senate Majority Leader Robert Byrd took the bill off of the floor. The Senate descended into rage, Gravel unsuccessfully trying to talk over the Senators' angry commotion. Stevens then rose and stated that "I feel like a father who has just arrived at the delivery room and found out his son has been stillborn." He accused Gravel of lying, adding Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus and President Jimmy Carter would take away 'millions of acres of Alaska from development'. Durkin then rose again; "We worked out an extension to protect Alaska, and he is torpedoing that now. I hope the press is listening, as well as every village in Alaska, so when the secretary (Andrus) invokes the Antiquities Act there will be no ticker-tape parade." Hard to hear over the anger of the Senate, Durkin then finally added that Alaskans should know that the compromise "foundered on two words, after forty-seven markups, and those two words are 'Mike Gravel.'"[57] Gravel argued that Stevens was selling out, and, in rebuttal, Stevens told the press that Gravel had broken his word, adding "Gravel is an international playboy who needs psychiatric help.", following "I'm not even sure if God could fathom his thinking."[57]

1978 plane crash

[edit]

On December 4, 1978, Stevens had a meeting in Anchorage with executives of the major pro-development lobby "Citizens for the Management of Alaska's Lands". On the same day, Governor of Alaska Jay Hammond, would be sworn in for a second term in Alaska's capital, Juneau. Tony Motley, the Chair of CMAL, arranged for a friend's private plane to pick them up after the inauguration had finished, and then fly them from Juneau to Anchorage so Stevens could attend the meeting. During takeoff from Anchorage International, the plane had risen only a few feet above the runway when it was hit by a sudden, strong gust of wind, which flipped the plane around and pointed it straight up in the air. In an attempt to re-orient the plane, the pilot pulled back the throttle, but the plane stalled and crashed violently into the ground. Out of the seven people on board, including the pilot, only Stevens and Motley survived the crash. The other five passengers, a group which included Ann Stevens, who was Stevens' wife of 2+1⁄2 decades, died on impact.[57]

Stevens's wife's death hit him very hard. On the day of the crash Gravel was on a trip to Saudi Arabia, but he flew back to attend Ann's funeral. Afterwards, Gravel asked a Stevens aide if he could express his condolences personally, but he was informed that Stevens didn't want to see him. Upon Stevens' return, he seemed "bitter and in terrible emotional pain", hinting in both Alaska and D.C. that he believed that the only reason he made the flight was that he had to rebuild the effort for a land bill back together, and that thus the primary reason was Mike Gravel killing the bill. Most of his remarks were not printed by reporters, who saw them as statements of someone "half-crazy with grief".[57]

However, on February 6, 1979, Stevens spoke to the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, which Udall chaired, which had just begun to debate the new edition of the lands bill, and he brought up the plane crash. "It was on that trip to Alaska to reconstitute the efforts for the coming year that I and Tony Motley, who passed away ... were involved in an accident", he said, the fact that Motley had survived seemingly lapsing his mind. "The trip was neither spur-of-the-moment nor stopgap. It was and is to me the beginning of this year's effort to achieve an acceptable D2 lands bill. As I am sure you realize, and many of you can imagine, the solution of the issue means even more to me than it did before." He shortly talked about the bill, before finally adding: "I think if that bill had passed, I might have a wife sitting and waiting when I get home tonight, too."[57][59]

In 1979, Stevens began to recruit primary challengers for the Democratic nomination to Gravel for his re-election campaign the following year. After some courting, Stevens decided to back Clark Gruening, the grandson of Ernest Gruening, who Gravel had defeated in the primary 12 years prior. Stevens had also reportedly (and unsuccessfully) attempted to court Tony Motley, the other survivor of the 1978 crash to run as the Republican nominee, but Motley stated he had only briefly touched upon entering the race with Stevens and that he was not a candidate.[57] The junior Gruening would defeat Gravel in the primary by a margin of 11 points.[60] Gruening would then lose the election to banker Frank Murkowski by 7 points.[61]

Early legislative achievements

[edit]

Stevens's fiery attitude greatly assisted him in pushing the highly controversial nomination of Alaska Governor Wally Hickel to the office of Interior Secretary through the workings of the Senate, as well as passing numerous major bills, such as the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in 1971, Title IX in 1972, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act in 1973, something which endeared the Senator to President Richard Nixon, and, an act which Stevens had picked as his key legislative achievement in 2006,[62] the Magnuson–Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, along with Washington Senator Warren Magnuson. Stevens's ability to do so helped propel him in popularity, allowing him to easily win re-election in 1970 in an upset. Stevens would continue to win re-election easily until his defeat in 2008 by Anchorage Mayor, Mark Begich, the son of former U.S. Representative from Alaska Nick Begich Sr..[5]

Pork barrel spending

[edit]Throughout his career, Stevens would bring in billions of dollars of pork barrel funding for Alaska, something which Stevens was unapologetic for, once stating "I'm guilty of asking for pork, and I'm proud of the Senate for giving it to me."[63] Stevens was nicknamed the "King of Pork" by CBS News[64] & NBC News.[65] In 2007, Texas received approximately $98 per person in federal appropriations, with a similar share accorded New York, while Alaska came in a far first place, receiving $4,300 per person. In his final year in the Senate, Stevens secured $469 million for Alaskan projects. Citizens Against Government Waste stated that Stevens had secured over a billion dollars in federal funding for Alaska from 1991 to 2000.[66][67]

Elections

[edit]After practicing private law for a year, Stevens ran for the U.S. Senate in 1962 and won the Republican nomination, defeating only trivial opposition. Stevens was considered a long-shot candidate against the popular former Governor and incumbent Democratic U.S. Senator Ernest Gruening, and he lost in the general election by a 16-point margin, a margin which was much closer than expected, considering Bartlett's 27-point win in the prior election, the stronghold of the Democratic Party in Alaska, and the long service of Gruening.[68][5] In 1968, Stevens once again ran for the U.S. Senate, but lost in the Republican primary to Anchorage Mayor Elmer E. Rasmuson. Rasmuson lost the general election to Democrat Mike Gravel. In December 1968, after the death of Alaska's other senator, Democrat Bob Bartlett, Governor Wally Hickel appointed Stevens to the seat.[69] Since Gravel took office ten days after Stevens did, Stevens was Alaska's senior senator for all but ten days of his forty-year tenure in the Senate. However, on the account of Stevens's long career in public service, and age, Gravel took no issue with the situation.

In a special election in 1970, Stevens won the right to finish the remainder of Bartlett's term. He won the seat in his own right in 1972, and was reelected in 1978, 1984, 1990, 1996 and 2002 elections. His final term expired in January 2009. Since his first election to a full term in 1972, Stevens never received less than 66% of the vote before his 2008 defeat for re-election.[70]

When asked if he would hypothetically accept the 2008 Republican vice presidential nomination if offered, Stevens replied "No. I've got too many things that I still want to do as a senator. Plus, I don't like the idea of a job where you sit around and wait for someone to die."[71]

Stevens lost his Senate re-election bid in 2008.[72] He won the Republican primary in August[73] and was defeated by Anchorage Mayor Mark Begich in the general election.[74] He was the longest-serving U.S. Senator in history to lose re-election, beating out Warren Magnuson, who had served over 36 years before his defeat to Slade Gorton in 1980.

Stevens, who would have been 90 years old on election day, had filed to run for a rematch against Begich in the 2014 election,[75] but he was killed in a plane crash on August 9, 2010.[76] Dan Sullivan would defeat Begich in the election by a margin of 3.1%.

Committees and leadership positions

[edit]

Stevens served as the Assistant Republican Leader (Whip) from 1977 to 1985. Stevens served as Acting Minority Leader during Howard Baker's run for president during the 1980 Republican primaries.[77] In 1994, after the Republicans took control of the Senate, Stevens was appointed chairman of the Senate Rules Committee. Stevens became the Senate's president pro tempore when Republicans regained control of the chamber as a result of the 2002 mid-term elections, during which the previous most senior Republican senator and former president pro tempore Strom Thurmond retired.

After Howard Baker retired in 1984, Stevens sought the position of Republican (and then-Majority) leader, running against Bob Dole, Dick Lugar, Jim McClure and Pete Domenici. As Republican whip, Stevens was theoretically the favorite to succeed Baker, but lost to Dole in a fourth ballot, by a vote of 28 - 25.[78]

Stevens chaired the Senate Appropriations Committee from 1997 to 2005, except for the 18 months when Democrats controlled the chamber. The chairmanship gave Stevens considerable influence among fellow Senators, who relied on him for home-state project funds. Even before becoming chairman of the Appropriations Committee, Stevens secured large sums of federal money for the State of Alaska.[79] Due to Republican Party rules that limited committee chairmanships to six years, Stevens gave up the Appropriations gavel at the start of the 109th Congress, in January 2005. He was succeeded by Thad Cochran of Mississippi.[80][81][82]

Stevens chaired the United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation during the 109th Congress, becoming the committee's ranking member after the Democrats regained control of the Senate for the 110th Congress. He resigned his ranking-member position on the committee due to his indictment.[83]

At various times, Stevens also served as chairman of the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee, the Senate Ethics Committee, the Arms Control Observer Group, and the Joint Committee on the Library of Congress.

Due to Stevens's long tenure and that of the state's sole congressman, Don Young, Alaska was considered to have clout in national politics well beyond its small population (the state was long the smallest in population and is currently 48th, ahead of only Wyoming and Vermont).[84]

Stevens was strongly considered for Secretary of Defense in the H.W. Bush Administration (1989–1993), a position which ultimately went to Dick Cheney.[55]

Political positions

[edit]Stevens was long considered a Rockefeller Republican and described as a liberal or moderate Republican,[85] managing Nelson Rockefeller's 1964 campaign in Alaska.[86] By one measure of all members of Congress from 1937 to 2002, Stevens, with a score of 0.183, usually voted to the left of the average Republican (who scored an average of 0.271 in the Senate and 0.300 in the House), and to the left of notable liberal & moderate Republicans such as Illinois Representative & 1980 presidential candidate John B. Anderson, with a score of 0.185,[87] Virginia Senator John Warner, with a score of 0.251,[88] & even Democrats such as Ohio Senator Frank Lausche, with a score of 0.200.[89] In 1977, the American Conservative Union gave Ted Stevens a ranking of less than 50%, indicating that Stevens had voted more liberally than he had conservatively.[90] In 1974, Stevens was given a 25% year-round rating, his lowest rating that year, putting him to the left of noted liberal Republicans Mark Hatfield,[91] Bob Packwood,[92] Charles Percy,[93] liberal Democratic leader Frank Church,[94] and even his Democratic colleague from Alaska, Mike Gravel.[95] In 1974, Stevens's lifetime rating was 43%. By the end of his career, Stevens had a 64.78% lifetime rating,[96] over 15% short of the required rating to be considered sufficiently conservative by the organization.[97]

Internet and net neutrality

[edit]

On June 28, 2006, the Senate Commerce Committee was in the final day of three days of hearings,[98] during which the Committee members considered more than two hundred amendments to an omnibus telecommunications bill. Stevens authored the bill, S. 2686,[99] the Communications, Consumer's Choice, and Broadband Deployment Act of 2006.

Senators Olympia Snowe (R-ME) and Byron Dorgan (D-ND) cosponsored and spoke on behalf of an amendment that would have inserted strong network neutrality mandates into the bill. In between speeches by Snowe and Dorgan, Stevens gave a vehement 11-minute speech using colorful language to explain his opposition to the amendment. Stevens referred to the Internet as "not a big truck", but a "series of tubes" that could be clogged with information. Stevens also confused the terms Internet and e-mail. Soon after, Stevens's interpretation of how the Internet works became a topic of amusement and ridicule by some in the blogosphere.[100] The phrases "the Internet is not a big truck" and "series of tubes" became internet memes and were prominently featured on U.S. television shows including Comedy Central's The Daily Show.

CNET journalist Declan McCullagh called "series of tubes" an "entirely reasonable" metaphor for the Internet, noting that some computer operating systems use the term 'pipes' to describe interprocess communication. McCullagh also suggested that ridicule of Stevens was almost entirely political, espousing his belief that if Stevens has spoken in a similar manner, yet in support of Net Neutrality, "the online chortling would have been muted or nonexistent."[101]

Logging

[edit]

Stevens was a long-standing proponent of logging and championed a plan that would allow 2,400,000 acres (9,700 km2) of roadless old growth forest to be clear-cut. Stevens said this would revive Alaska's timber industry and bring jobs to unemployed loggers; however, the proposal would mean that thousands of miles of roads would be constructed at the expense of the United States Forest Service, judged to cost taxpayers $200,000 per job created.[102]

Abortion

[edit]According to On the Issues[103] and NARAL,[104] Stevens had a mildly anti-abortion voting record, despite some notable pro-abortion votes.[105]

However, as a former member of the moderate Republican Main Street Partnership, Stevens supported human embryonic stem cell research.[106]

Global warming

[edit]Stevens was long an avowed skeptic of anthropogenic climate change, instead believing the threat was from natural causes. In 2004, Stevens said "No place is experiencing a more startling change from rising global temperatures than Alaska. Among the consequences are sagging roads, crumbling villages, dead trees, catastrophic fires and possible disruption of marine life. These problems will cause Alaska hundreds of millions of dollars. Alaska is harder hit by global climate change than any place in the world."[107] At a Senate Commerce Committee hearing in 2005, Stevens warned Congress to approach climate change with caution, stating "Dr. Syun-Ichi Akasofu sent me his most recent assessment earlier this month. I hope you all know that we helped finance three, maybe four icebreaker research vessels now for the third year in the Arctic Ocean to try and really keep track of what is happening there. He noted the amount of CO2 and CH4 now in the air is well above what the earth has experienced during the last 450,000 years and climate change is in progress in full steam in the Arctic. But he emphasized that there is 'no definitive proof' that receding glaciers and shrinking sea ice 'are caused entirely and specifically by the greenhouse effect.'", adding "I have urged my colleagues in the Senate not to substitute casual judgments for sound science. That would only lead to confusion, which Dr. Akasofu has warned me may be more dangerous than global warming itself."[108]

In early 2007, he acknowledged that humans were changing the climate, and began supporting legislation to combat climate change. "Global climate change is a very serious problem for us, becoming more so every day," he said at a Senate hearing in February 2007, adding that he was "concerned about the human impacts on our climate". He then spoke to the St. Petersburg Times, stating "We've got global climate change, and it's coming about partly naturally and part of it may be, I believe, caused by the accumulation of the activities of man."[109] But in September 2007, he claimed, "We're at the end of a long term of warming.", adding "700 to 900 years of increased temperature," and then "If we're close to the end of that, that means that we'll starting getting cooler gradually, not very rapidly, but cooler once again and stability might come to this region for a period of another 900 years."[50][107]

Civil rights

[edit]Stevens voted in favor of the bill establishing Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a federal holiday and the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987 (as well as to override President Reagan's veto).[110][111][112] Stevens was one of the sponsors the Title IX amendment to the Education Amendments of 1972,[11] and was influential in its passage, with the Washington Post nicknaming him "The Father of Title IX".[12] The American Civil Liberties Union rated Stevens 20% in 2002, indicating an anti civil rights voting record, and the NAACP rated Stevens 14% in 2006, indicating an anti-affirmative action stance. Stevens would, however, vote against an amendment to ban affirmative action in federally funded businesses in 1995.[113]

LGBT+ rights

[edit]Stevens voted in favor of an amendment to classify abuse based on sexual orientation a hate crime in 2000, though he voted against a similar amendment in 2002.[113] Stevens voted in favor of the Defense of Marriage Act.[114] The Human Rights Campaign rated Stevens 0% in 2006, indicating an anti-gay rights stance.[113]

U.S. Supreme Court

[edit]Stevens voted in favor of the nominations of Robert Bork[115] and Clarence Thomas[116] to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Criticism of political positions and actions

[edit]During his tenure as Senator, Stevens was subject to frequent criticism that included:

- Citizens Against Government Waste accused Stevens of pork barrel politics and kept a list of his pet projects.[117]

- In 2005, Stevens strongly supported federal transportation funds to build the Gravina Island Bridge, which quickly became derided due to its price tag (approximately $398 million) and as an unnecessary Bridge to Nowhere. Stevens threatened to quit the Senate if the funds were diverted.[118]

- Additionally, he received criticism for introducing a bill in January 2007 that would heavily restrict access to social networking sites from public schools and libraries. Sites falling under the language of this bill could have included MySpace, Facebook, Digg, English Wikipedia, and Reddit.[119][120][121]

- In 2007, Stevens added $3.5 million into a Senate omnibus bill to help finance an airport which serves a remote Alaskan island.[122] The proposed airstrip would allow around a hundred permanent residents of Akutan access, but the biggest beneficiary would have been the Seattle-based Trident Seafoods, a corporation which reportedly operated "one of the world's largest seafood processing plants," on a volcanic Aleutians island.[122] In December 2006, a federal grand jury involved in the Alaska political corruption probe ordered Trident (as well as other seafood companies) to render private documents about ties to the senator's youngest son, former Alaska Fisheries Marketing Board Chairman and, at the time, the incumbent President of the Alaska State Senate Ben Stevens.[122] Trident's chief executive, Charles Bundrant, was a longtime supporter of the elder Stevens, and Bundrant with his family donated $17,300 in a time period spanning since 1995 to Stevens's political campaigns and another $10,800 to his leadership PAC, while also donating $55,000 to the National Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee.[122]

Controversies

[edit]In December 2003, the Los Angeles Times reported that Stevens had taken advantage of lax Senate rules to use his political influence to obtain a large amount of his personal wealth.[123] According to the article, while Stevens was already a millionaire "thanks to investments with businessmen who received government contracts or other benefits with his help," the lawmaker who was in charge of $800 billion a year, writes "preferences he wrote into law," from which he then benefits.[123]

Home remodeling and VECO

[edit]

On May 29, 2007, the Anchorage Daily News reported that the FBI and a federal grand jury were investigating an extensive remodeling project at Stevens's home in Girdwood. Stevens's Alaska home was raided by the FBI and IRS on July 30, 2007.[124] The remodeling work doubled the size of the modest home. The remodel in 2000 was organized by Bill Allen, a founder of the VECO Corporation (an oil-field service company) and was alleged by prosecutors to have cost VECO and the various contractors $250,000 or more.[125] However, the residential contractor who finished the renovation for VECO, Augie Paone, "believes the [Stevens's] remodeling could have cost – if all the work was done efficiently – around $130,000 to $150,000, close to the figure Stevens cited last year."[126] Stevens paid $160,000 for the renovations "and assumed that covered everything".[127]

In June, the Anchorage Daily News reported that a federal grand jury in Washington, D.C., heard evidence in May about the expansion of Stevens's Girdwood home and other matters connecting Stevens to VECO.[128] In mid-June, FBI agents questioned several aides who worked for Stevens as part of the investigation.[129] In July, Washingtonian magazine reported that Stevens had hired "Washington's most powerful and expensive lawyer", Brendan Sullivan Jr., in response to the investigation.[130] In 2006, during wiretapped conversations with Bill Allen, shortly after the VECO offices were searched and Allen agreed to cooperate with the investigation, Stevens expressed worries over legal complications arising from the sweeping federal investigations into Alaskan politics. "The worst that can happen to us is we run up a bunch of legal fees, and might lose and we might have to pay a fine, might have to serve a little time in jail. I hope to Christ it never gets to that, and I don't think it will," Stevens said.[131][132] Stevens continued, "I think they might be listening to this conversation right now, for Christ Sake."[133] On the witness stand, Allen testified that VECO staff who had worked on his own house had charged "way too much", leaving him uncertain – that he would be embarrassed to bill Stevens for overpriced labor.[134]

Former aide

[edit]The Justice Department also examined whether federal funds that Stevens steered to the Alaska SeaLife Center may have illegally benefited an aide.[135] However, no charges were ever filed.

Bob Penney

[edit]In September 2007, The Hill reported that Stevens had "steered millions of federal dollars to a sportfishing industry group founded by Bob Penney, a longtime friend". In 1998, Stevens invested $15,000 in a Utah land deal managed by Penney; in 2004, Stevens sold his share of the property for $150,000.[136]

Trial, conviction, and reversal

[edit]Indictment

[edit]

On July 29, 2008, Stevens was indicted by a federal grand jury on seven counts of failing to properly report gifts,[137] a felony, and found guilty at trial three months later (October 27, 2008).[138] The charges related to renovations to his home and alleged gifts from VECO Corporation, claimed to be worth more than $250,000.[139][140] The charges were associated with those exposed in what became known as "Operation Polar Pen". The indictment followed a lengthy investigation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) for possible corruption by Alaskan politicians and was based in part on Stevens's extensive relationship with Bill Allen. Allen owned racehorses, including a partnership in the stud-horse So Long Birdie, which included Stevens and eight others, and which was managed by Bob Persons.[141] The FBI not only had calls between Allen and Stevens (made after Allen became a cooperating witness), they had thousands of wiretapped conversations involving the phones of both Allen and VECO Vice President Rick Smith. They had also videotaped meetings between Allen and state legislators at VECO's hotel suite in Juneau, the state capitol. Allen had testified that he bribed Ted's son Ben, the former Alaska Senate president. A former VECO employee said he did campaign fundraising work for Stevens while on VECO's payroll, a violation of federal law.[142] Allen, then an oil service company executive, had earlier pleaded guilty (sentence suspended pending his cooperation in gathering evidence and giving testimony in other trials) to bribing several Alaskan state legislators. Stevens declared, "I'm innocent," and pleaded not guilty to the charges in a federal district court on July 31, 2008. Stevens asserted his right to a speedy trial so he could have the opportunity to clear his name promptly and requested that the trial be held before the 2008 election.[143][144]

U.S. District Judge Emmet G. Sullivan, on October 2, 2008, denied the mistrial petition of Stevens's chief counsel, Brendan Sullivan, that made allegations of withholding evidence by prosecutors. Thus, the latter were admonished and would submit themselves for an internal probe by the United States Department of Justice. Brady v. Maryland requires prosecutors to give a defendant any material exculpatory evidence. Judge Sullivan had earlier admonished the prosecution for sending home to Alaska a witness who might have helped the defense.[145][146]

The case was prosecuted by Principal Deputy Chief Brenda K. Morris, Trial Attorneys Nicholas A. Marsh and Edward P. Sullivan of the Criminal Division's Public Integrity Section, headed by Chief William M. Welch II; and Assistant U.S. Attorneys Joseph W. Bottini and James A. Goeke from the District of Alaska.

Guilty verdict and repercussions

[edit]On October 27, 2008, Stevens was found guilty of all seven counts of making false statements. Stevens was only the fifth sitting senator to be convicted by a jury in U.S. history,[147] and the first since Senator Harrison A. Williams (D-NJ) in 1981[148] (although Senator David Durenberger (R-MN) pleaded guilty to a felony more recently, in 1995). Stevens faced a maximum penalty of five years per charge.[149] His sentencing hearing was originally arranged February 25, but his attorneys told Judge Sullivan they would file applications to dispute the verdict by early December.[150] However, it was thought unlikely that Stevens would spend significant time in prison.[151]

Within a few days of his conviction, Stevens faced bipartisan calls for his resignation. Both parties' presidential candidates, Barack Obama and John McCain, were quick to call for Stevens to stand down. Obama said Stevens needed to resign to help "put an end to the corruption and influence-peddling in Washington".[152] McCain said Stevens "has broken his trust with the people" and needed to step down, a call echoed by his running mate, Sarah Palin, governor of Stevens's home state.[153] Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, as well as fellow Republican Senators Norm Coleman, John Sununu and Gordon Smith also called for Stevens to resign. McConnell said there would be "zero tolerance" for a convicted felon serving in the Senate, strongly hinting that he would support Stevens's expulsion from the Senate unless Stevens resigned first.[154][155] Late on November 1, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid confirmed that he would schedule a vote on Stevens's expulsion, saying "a convicted felon is not going to be able to serve in the United States Senate."[156]

Nonetheless, during a debate with his opponent, Anchorage, Alaska Mayor Mark Begich, days after his conviction, Stevens continued to claim innocence. "I have not been convicted. I have a case pending against me, and probably the worst case of prosecutorial misconduct by the prosecutors that is known." Stevens also cited plans to appeal.[157] On November 4, 2008, eight days after his conviction, Begich went on to defeat Stevens by 3,724 votes, a 1.3% margin. Stevens was the longest-serving U.S. Senator in history to have ever lost a bid for re-election, beating out Warren Magnuson's record in 1980.[158] Had Stevens won his re-election bid, and then been expelled, a special election would have been held to fill his seat through the remainder of the term, until January 2015.[159] No sitting U.S. senator has ever been expelled since the Civil War.

On November 13, Senator Jim DeMint of South Carolina announced he would move to have Stevens expelled from the Senate Republican Conference (caucus) regardless of the results of the election. (Absentee, provisional, and early ballots were, at the time, still being tallied in the close election.) Losing his caucus membership would cost Stevens his committee assignments.[160] However, DeMint later decided to postpone offering his motion, saying that while there were enough votes to throw Stevens out, it would be moot if Stevens lost his reelection bid.[161] Stevens ended up losing the Senate race, and on November 20, 2008, gave his last speech to the Senate, which was met with a loud standing ovation by the other members of the chamber.[162]

Government concealment of evidence

[edit]In February 2009, FBI agent Chad Joy filed a whistleblower affidavit, alleging that prosecutors and FBI agents conspired to withhold and conceal evidence that could have resulted in acquittal.[163] In his affidavit, Joy alleged that prosecutors intentionally sent a key witness, former VECO employee Robert Burnette "Rocky" Williams, who had testified before a grand jury in 2006, back home to Alaska.[164] Williams had performed poorly during a mock cross-examination.[165] The prosecution informed Judge Sullivan that it had concerns regarding the health of the witness. Williams was terminally ill,[165] experiencing liver failure, which causes confusion.[166][164] He died on December 30, 2008.[165] Joy further alleged that the prosecutors intentionally withheld Brady material including redacted prior statements of a witness, and a memo from Bill Allen stating that Senator Stevens probably would have paid for the goods and services if asked. Joy further inferred that a female FBI agent had an inappropriate relationship with Allen, who also gave gifts to FBI agents and helped one agent's relative get a job.[167]

As a result of Joy's affidavit and claims by the defense that prosecutorial misconduct had caused an unfair trial, Judge Sullivan ordered a hearing to be held on February 13, 2009, to determine whether a new trial should be ordered.[168] At the February 13 hearing, Judge Sullivan held the prosecutors in contempt for having failed to deliver documents to Stevens's legal counsel.[169]

Convictions voided and indictment dismissed

[edit]On April 1, 2009, on behalf of U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, Paul O'Brien submitted a "Motion of The United States To Set Aside The Verdict And Dismiss The Indictment With Prejudice" in connection with case No. 08-231. Federal judge Emmet G. Sullivan soon signed the order. During the trial, Sullivan had expressed anger after Allen, the prosecution's witness, recounted a note Stevens sent him insisting that a bill for work Veco had done be sent to Stevens. Allen said that Persons subsequently told him that Stevens was just "covering his ass".[170] Holder, who had taken office only three months earlier, stated that it was "in the interest of justice" not to hold a new trial,[171] adding that he was "horrified".[172] After Sullivan held the prosecutors in contempt, Holder replaced the entire trial team, including top officials in the public integrity section. The discovery of a previously undocumented interview with Allen raised the possibility prosecutors had knowingly allowed Allen to perjure himself. Allen said the fair market value of the repairs to the Stevenses' house was around $80,000, considerably less than the $250,000 he said it cost at trial.[173] More seriously, Allen said in the interview that he didn't recall talking to Persons, a friend of Stevens, regarding the repair bill for the Stevenses' house. Even without the notes, Stevens's attorneys claimed Allen was lying about the conversation.[170]

Later that day, Stevens's attorney, Brendan Sullivan, said Holder's decision was forced by "extraordinary evidence of government corruption". He also claimed that prosecutors not only withheld evidence but "created false testimony that they gave us and actually presented false testimony in the courtroom".[174]

On April 7, 2009, Judge Sullivan formally accepted Holder's motion to set aside the verdict and throw out the indictment, declaring, "There was never a judgment of conviction in this case. The jury's verdict is being set aside and has no legal effect," and calling it the worst case of prosecutorial misconduct he'd ever seen.[175] He also initiated a criminal contempt investigation of six members of the prosecution. Although an internal investigation by the Office of Professional Responsibility was already underway, Sullivan said he was not willing to trust it due to the "shocking and disturbing" nature of the misconduct.[176]

In 2012, the Special Counsel report on the case was released. It said,[177]

The investigation and prosecution of U.S. Senator Ted Stevens were permeated by the systematic concealment of significant exculpatory evidence which would have independently corroborated Senator Stevens's defense and his testimony, and seriously damaged the testimony and credibility of the government's key witness.

— Special Counsel Report[178]

Upon the release of the Special Counsel report, the Stevens defense team released an analysis of its own, which said, "The meticulous detail paints a picture of the government's shocking conduct in which prosecutors repeatedly ignored the law. The Report shows how prosecutors abandoned their oath of office and the ethical standards of their profession. They abandoned all decency and sound judgment when they indicted and prosecuted an 84-year old man who served his country in World War II combat, and who served with distinction for 40 years in the U.S. Senate."[179]

A statement issued by Stevens's widow Catherine said, "I can say that the Stevens family continues to be shocked by the depth and breadth of the government's misconduct."[180]

Mark Bonner, associate professor of law at Ave Maria School of Law, has argued that the court acted improperly by appointing a special prosecutor, claiming that, among other things, the "trial court had no lawful authority to hold the prosecutors in contempt for Brady violations..."[181]

Achievements and honors

[edit]

Stevens was voted Alaskan of the Century in 2000 by the Alaskan of the Year Committee. In the same year, the Alaska Legislature renamed the Anchorage airport, the largest in the state, to the Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport.[182]

The Ted Stevens Foundation is a charity established to "assist in educating and informing the public about the career of Senator Ted Stevens". The chairman is Tim McKeever, a lobbyist who was treasurer of Stevens's 2004 campaign. In May 2006, McKeever said the charity was "nonpartisan and nonpolitical", and that Stevens does not raise money for the foundation, although he has attended some fund-raisers.[183]

November 18, 2003, the senator's 80th birthday, was declared Senator Ted Stevens Appreciation Day by Governor of Alaska Frank Murkowski.[184]

When discussing issues that were especially important to him (such as opening up the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil drilling), Stevens wore a necktie with The Incredible Hulk on it to show his seriousness.[185] Marvel Comics has sent him free Hulk paraphernalia and has thrown a Hulk party for him.[186] On December 21, 2005, Stevens said the vote to block drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge "has been the saddest day of my life".[187]

On December 30, 2006, Stevens delivered a eulogy of Gerald R. Ford at the 38th President's funeral service.[188] On April 13, 2007, Stevens was recognized as the longest-serving (38 years) Republican senator in history. (He served in total forty years and ten days.) Senator Daniel Inouye, a Democrat from Hawaii, referred to Stevens as "The Strom Thurmond of the Arctic Circle". Stevens held this record until he was overtaken by Orrin Hatch on January 14, 2017.[189]

Death and legacy

[edit]

On August 9, 2010, Stevens and seven other passengers including former NASA administrator Sean O'Keefe were aboard a de Havilland Canada DHC-3 Otter plane when it crashed about 17 miles north of Dillingham, Alaska,[190] while en route to a private fishing lodge. Stevens was confirmed dead in the crash via a statement from his family.[191] He and others were aboard the single-engine plane registered to Anchorage-based GCI Communication.[192]

As Stevens's death was confirmed, Alaskan and national political figures from all sides of the political spectrum spoke highly of the man many Alaskans knew as "Uncle Ted".[193][194] Senator Lisa Murkowski said of Stevens: "His entire life was dedicated to public service – from his days as a pilot in World War II to his four decades of service in the United States Senate. He truly was the greatest of the 'Greatest Generation.'"[195] Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell stated "In the history of our country, no one man has done more for one state than Ted Stevens. His commitment to the people of Alaska and his nation spanned decades, and he left a lasting mark on both." Senator Mary Landrieu also spoke "Ted always said, 'To hell with politics. Do what is best for Alaska.' He never apologized for fighting for his state, and Alaska is better for it today."[196]

The Pacific Aviation Museum Pearl Harbor honored Stevens with a plaque and a display of memorabilia of his wartime service in China-Burma-India. Senator Mark Begich, his successor, stated, "Over his four decades of public service in the U.S. Senate, Senator Stevens was a forceful advocate for Alaska who helped transform our state in the challenging years after Statehood"[197] and former president George H. W. Bush released a statement that "Ted Stevens loved the Senate; he loved Alaska; and he loved his family – and he will be dearly missed."[198] President Barack Obama said in a statement, "Ted Stevens devoted his career to serving the people of Alaska and fighting for our men and women in uniform."[2]

Memorial services

[edit]Hundreds of Alaskans attended a memorial Mass for Stevens at Holy Family Cathedral in downtown Anchorage on August 16. On August 17, mourners paid their respects as he laid in a closed casket at All Saints Episcopal Church, also in downtown Anchorage, which was Stevens's home church. His funeral at Anchorage Baptist Temple on August 18 was attended by some three thousand people, including then-Vice President Joe Biden, former Governor Sarah Palin, then-Governor Sean Parnell and three other former governors, eleven senators, nine former senators, and two congressmen.[199] Stevens was interred at Arlington National Cemetery on September 28.[200]

USS Ted Stevens

[edit]In January 2019, the US Navy announced that a Flight III Arleigh Burke-class destroyer would be named USS Ted Stevens (DDG-128). It will be constructed at Huntington Ingalls Industries' Ingalls shipbuilding division in Pascagoula, Mississippi.[201]

Electoral history

[edit]See also

[edit]- Alaska political corruption probe

- List of fatalities from aviation accidents

- Mount Stevens

- List of federal political scandals in the United States

Notes and references

[edit]^ This office is now known as the Solicitor of the Interior. When Stevens held this role, it was the 2nd highest position, behind Secretary. After 1995, it became the 3rd highest role, behind Secretary and Deputy Secretary.

- ^ "Former Sen. Stevens killed in plane crash". KTUU.com. August 10, 2010. Archived from the original on October 26, 2011. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ^ a b "Former Sen. Ted Stevens dies in Alaska plane crash". NBC News. August 10, 2010. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ a b "Ted Stevens' Biography". Ted Stevens Foundation. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ "Biography of Ted Stevens". Associated Press. August 10, 2010. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mitchell, Donald Craig (May 13, 2016). "From Mr. Alaska to Uncle Ted: How Stevens became Alaska's most influential leader". Anchorage Daily News. Archived from the original on January 29, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ a b Welch, Craig (November 3, 2005). "Senator has long pushed for drilling". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on May 5, 2023. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- ^ Raju, Manu (August 10, 2010). "Stevens was 'larger than life'". Politico. Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Kavanagh, Jim. "Ted Stevens a towering figure in Alaska". CNN. Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Ornstein, Norman (August 17, 2010). "Ornstein: Rostenkowski and Stevens Were Master Lawmakers". Roll Call. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b "The life and legacy of former Sen. Ted Stevens". NBC News. August 10, 2010. Archived from the original on May 6, 2023. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- ^ a b deVarona, Donna (August 17, 2010). "Ted Stevens Was Guardian Angel of Women in Sports". Women's eNews. Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ a b "U.S. Senator vows support of Title IX". The Washington Post. February 3, 1995. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "Ted Stevens warrants a spot in sports hall of fame". Anchorage Daily News. November 25, 2011. Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "Stevens says, 'I am innocent' after corruption conviction". CNN. October 27, 2008. Archived from the original on August 20, 2010. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ "Sen. Ted Stevens' conviction set aside". CNN. April 7, 2009. Archived from the original on August 20, 2010. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ Toobin, Jeffrey (January 3, 2011). "Casualties of Justice". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Frazier, Nathan A. (2011). "Amending for Justice's Sake: Codified Disclosure Rule Needed to Provide Guidance to Prosecutor's Duty to Disclose". Florida Law Review. 63 (3): 771–800. Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "Horrible Details Of Ted Stevens Crash Emerge". npr. Archived from the original on May 12, 2023. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

- ^ Theodore Fulton "Ted" Stevens genealogy. Archived October 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Rootsweb.com. Retrieved on May 31, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Whitney, David (August 8, 1994). "Formative years: Stevens's life wasn't easy growing up in the depression with a divided family". Anchorage Daily News. p. A1. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020 – via Congressional Record.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Mitchell, Donald Craig (2001). Take My Land, Take My Life: The Story of Congress's Historic Settlement of Alaska Native Land Claims, 1960–1971. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press.

- ^ "Redondo Remembers Ted Stevens". August 13, 2010.

- ^ "Presidents | DKE". Archived from the original on May 12, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ a b c "With the editors ..." 64 Harvard Law Review vii (1950).

- ^ Stevens, Theodore F. (1950). "Erie R.R. v. Tompkins and the Uniform General Maritime Law". Harvard Law Review. 64 (2): 88–112. doi:10.2307/1336176. JSTOR 1336176. Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Whitney, David (August 9, 1994). "The road north: Needing work, Stevens borrows $600, answers call to Alaska". Anchorage Daily News. Archived from the original on June 9, 2011.

- ^ Ely, Northcutt (December 16, 1994). "Doctor Ray Lyman Wilbur: Third President of Stanford & Secretary of the Interior". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2007.

- ^ Alaska Mining Hall of Fame Foundation. (2006). "Emil Usibelli (1893–1964)." Archived August 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2007-06-05.

- ^ "Recovery rapid for Sen. Stevens, doctor reports". (Oregon). Associated Press. December 6, 1978. p. 5A. Archived from the original on May 14, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2020 – via Eugene Register-Guard.

- ^ "Alaskan jet crash kills senator's wife". Lodi News-Sentinel. (California). UPI. December 5, 1978. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 2, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ "Jet crash injures Sen. Stevens, kills his wife, four other persons". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. December 5, 1978. p. 4A. Archived from the original on June 1, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ Hosenball, Mark (August 11, 2010). "NTSB Warned About Alaska Pilots' Risky Ways – and Ted Stevens Argued". Newsweek. Archived from the original on August 15, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ "Ann Stevens Room & Galleria". Anchorage Public Library. Archived from the original on May 12, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ Stevens family says goodbye to a stalwart sister Archived December 9, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Alaska Dispatch News, Sean Doogan, February 27, 2014.(Updated: May 31, 2016). Retrieved 29 May 2017.