Levée en masse

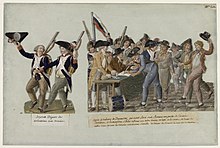

Levée en masse (French pronunciation: [ləve ɑ̃ mɑs] or, in English, mass levy[1]) is a French term used for a policy of mass national conscription, often in the face of invasion.

The concept originated during the French Revolutionary Wars, particularly for the period following 16 August 1793,[2] when able-bodied men aged 18 to 25 were conscripted. The concept of mass conscription was kept in place during the Napoleonic Wars.

The term is also applied to other historical examples of mass conscription.[3]

Terminology

[edit]The term levée en masse denotes a short-term requisition of all able-bodied men to defend the nation and its rise as a military tactic may be viewed in connection with the political events and developing ideology in revolutionary France—particularly the new concept of the democratic citizen as opposed to a royal subject.[4]

Central to the understanding that developed (and was promoted by the authorities) of the levée is the idea that the new political rights given to the mass of the French people also created new obligations to the state. As the nation now understood itself as a community of all people, its defense also was assumed to become a responsibility of all. Thus, the levée en masse was created and understood as a means to defend the nation by the nation.

Historically, the levée en masse heralded the age of national participation in warfare and displaced restricted forms of warfare, such as the cabinet wars (1715–1792), when armies of professional soldiers fought without the general participation of the population.

History

[edit]French Revolutionary Wars

[edit]The first modern use of levée en masse occurred during the French Revolutionary Wars. Under the Ancien Régime, there had been some conscription (by ballot) to a militia, milice, to supplement the large standing army in times of war. This was unpopular with the peasant communities on which it fell, and was one of their grievances which they expected to be addressed by the French Estates General when it was convened in 1789, to strengthen the French monarchy. When this instead led to the French Revolution, the milice was duly abolished by the National Assembly.

Pre-war through early war days

[edit]As early as 1789, leaders had considered how they would sustain their revolutionary army. In December, Dubois de Crancé, who was both "a man of the left" and "a military man, having served as a King's Musketeer",[5] spoke to the National Assembly on behalf of its military committee. He called for "a people's army, recruited by universal conscription, from which there could be no escape by purchase of a replacement".[5] He said to the National Convention: "And so I say that in a nation which seeks to be free but which is surrounded by powerful neighbours and riddled with secret, festering factions, every citizen should be a soldier and every soldier should be a citizen, if France does not wish to be utterly obliterated".[5] Yet the Committee was not ready to enact conscription, and would not until dire war deficits demanded more men.

The progression of the Revolution came to produce friction between France and its European neighbors, who grew determined to invade France to restore the monarchy. War with Prussia and Austria began in April 1792. Decrees such as that of 19 November 1792 reflect the fact that "the deputies were in no mood for caution".[6] The convention's decree stated that: "The National Convention declares, in the name of the French nation, that it will grant fraternity and assistance to all peoples who wish to recover their liberty, and instructs the Executive Power to give the necessary orders to generals to grant assistance to these peoples and to defend those citizens who have been—or may be—persecuted for their attachment to the cause of liberty. The National Convention further decrees that the Executive Power shall order the generals to have this decree printed and distributed in all the various languages and in all the various countries of which they have taken possession".[6] Their decree signalled to foreign powers, namely Britain, that France was out for conquest, not just political reformation of its own lands.

The French army at that time contained a mixture of what was left of the old professional army and volunteers. This ragtag group was spread thin, and, by February 1793, the new regime needed more men, so the National Convention passed a decree on 24 February allowing for the national levy of about 300,000 with each French département to supply a quota of recruits. By March 1793, France was at war with Austria, Prussia, Spain, Britain, Piedmont, and the United Provinces. The introduction of recruitment for the levy in the Vendée, a politically and religiously conservative region, added to local discontent over other revolutionary directives emanating from Paris, and on 11 March the Vendée erupted into civil war—just days after France declared war on Spain and adding further strains on the French armies' limited manpower.[7] By some accounts, only about half this number appears to have been actually raised, bringing the army strength up to about 645,000 in mid-1793, and the military situation continued to deteriorate, particularly when Mainz fell on 23 July 1793.[citation needed]

In response to this desperate situation, at war with European states, and insurrection, Paris petitioners and the fédérés demanded that the Convention enact a levée en masse. In response, Convention member Bertrand Barère asked the convention to "decree the solemn declaration that the French people was going to rise as a whole for the defense of its independence".[8] The Convention fulfilled Barere's request on 16 August, when they stated that the levée en masse would be enacted.

Levée en masse decreed

[edit]

The decree was enacted by the National Convention on 23 August 1793, having been penned by Barère in conjunction with Lazare Carnot. The decree read in ringing terms, beginning: "From this moment until such time as its enemies shall have been driven from the soil of the Republic, all Frenchmen are in permanent requisition for the services of the armies. The young men shall fight; the married men shall forge arms and transport provisions; the women shall make tents and clothes and shall serve in the hospitals; the children shall turn old linen into lint; the old men shall betake themselves to the public squares in order to arouse the courage of the warriors and preach hatred of kings and the unity of the Republic."[9]

All unmarried able-bodied men between 18 and 25 were requisitioned with immediate effect for military service. This significantly increased the number of men in the army, which reached a peak of about 1,500,000 in September 1794, although the actual fighting strength probably peaked at no more than 800,000. In addition, as the decree suggests, much of the civilian population was turned towards supporting the armies through armaments production and other war industries as well as supplying food and provisions to the front. As Barère put it, "…all the French, both sexes, all ages are called by the nation to defend liberty".

Text of the French Revolution's levée en masse

[edit]Translated and summarized Levée en Masse[10]

- Henceforth, until the enemies have been driven from the territory of the republic, the French people are in permanent requisition for army service. The young men shall go to battle; the married men shall forge arms and transport provision; the women shall make tents and clothes, and shall serve in the hospitals; the children shall turn old linen into lint; the old men shall repair to the public places, to stimulate the courage of the warriors and preach the unity of the Republic and hatred of kings

- National buildings shall be converted into barracks; public places into armament workshops; the soil of cellars shall be washed in lye to extract saltpeter therefrom.

- Arms of the caliber shall be turned over exclusively to those who march against the enemy; the service of the interior shall be carried on with fowling pieces and sabers.

- Saddle horses are called for to complete the cavalry corps; draught horses, other than those employed in agriculture, shall haul artillery and provisions

- The Committee of Public Safety is charged for taking all measures necessary for establishing, without delay, a special manufacture of arms of all kinds, in harmony with the élan and the energy of the French people. Accordingly, it is authorized to constitute all establishments, manufactories, workshops, and factories deemed necessary for the execution of such works, as well as the requisition for such purpose, throughout the entire extent of the Republic, the artists and workmen who may contribute to their success. For such purpose a sum of 30,000,000 taken from the 498,200,000 livres in assignats in reserve in the “Fund of the Three Keys,” shall be placed at the disposal of the Minister of War (Carnot). The central establishment of said special manufacture shall be established at Paris.

- The representatives of the people dispatched for the execution of the present law shall have similar authority in their respective arrondissements, acting in concert with the Committee of Public Safety; they are invested with the ultimate powers attributed to the representatives of the people with armies.

- No one may obtain a substitute for service to which he is summoned. The public functionaries shall remain at their posts.

- The levy shall be general. Unmarried citizens or childless widowers, from eighteen to twenty-five years, shall go first; they shall meet, without delay, at the chief town of their districts, where they shall practice manual exercise daily, while awaiting the hour of departure.

- The representatives of the people shall regulate the musters and marches so as to have armed citizens arrive at the points of assembling only in so far as supplies, munitions, and all that constitutes the material part of the army exist in sufficient proportion.

- The points of assembling shall be determined by circumstances, and designated by the representatives of the people dispatched for the execution of the present decree, upon the advice of the generals, in co-operation with the Committee of Public Safety and the provisional Executive Council.

- The battalion organized in each district shall be united under a banner bearing the inscription: The French people risen against tyrants.

- Such battalions shall be organized according to established decrees, and their pay shall be the same as that of the battalions at the frontiers.

- In order to collect supplies in sufficient quantity, the farmers and managers of national property shall deposit the produce of such property, in the form of grain, in the chief town of their respective districts.

- Owners, farmers, and others possessing grain shall be required to pay, in kind, arrears of taxes, even the two-thirds of those of 1793, on the rolls which have served to effect the last payment.

- [Articles 15 and 16 name assistants to the Deputies on Mission—among them Chabot and Tallien—and give orders to the envoys of the primary assemblies concerning the mission assigned to them.]

- The Minister of War is responsible for taking all measures necessary for the prompt execution of the present decree; a sum of 50,000,000 from the 498,000,000 livres in assignats on the “Fund of the Three Keys,” shall be placed at his disposal by the National Treasury.

- The present decree shall be conveyed to the departments by special messengers.

Conscription

[edit]According to historian Howard G. Brown, “The French state’s panicky response to a crisis of its own making soon led to an excessive military build-up. Enemy forces consisted of no more than 81,000 Austrians and Prussians, supported by 6,000 Hessians and a few thousand émigrés. Against these paltry forces France decided to mobilize an army of 450,000 men, larger than any army Europe had ever seen.”[11] Depending on the source, the exact number of those conscripted ranges from 750,000 to around 800,000. However, the values cannot be verified and is a reconstructed estimate because the French Government was in no position to give accurate figures at the time. One source states the official numbers in February 1793, were 361,000 men, in January 1794, were 670,900 men, in April 1794, 842,300, with the maximum reached in September 1794, 1,108,300. “However these figures are worth very little.”[12] The figures “designated all who were on the rolls as being maintained at the expense of the state, including therefore all those disabled by illness, capture or even desertion...The best guess seems to be that about 800,000 were available for active service” in 1794.[13] Other sources give estimates that around 750,000 men were actively serving in the French Army.[13] “The Commission of Armies alone could not identify the armies, let alone its location or strength.”[13] Also, there were many individuals that deserted the army, but the exact number of individuals that deserted is also an estimation based on the number of individuals that were caught or came back to France due to amnesty laws.[13]

When looking at the makeup of the French army overall, the majority of the individuals in the army consisted of the peasant, farming class in contrast to the rich and urban workers who were given special privileges and exemptions.[13] The rich were able to buy remplaçants, replacements, by paying poorer males who needed the money to take their places.[12] Males that had office jobs in the city were also exempted from serving in the French army as well as males that could read and write and who worked in the government.[13] The overall make up of the army was unevenly distributed among the different regions in France. The Levée expected that one male was conscripted for every 138 inhabitants.[13] However, in reality each region did not follow this conscription rule. There were departments that conscribed more individuals like Puy-de-Dôme, the Haute-Loire, and Yonne, located more in central France[13] while other areas that sent less than expected, like Seine, Rhône, and Basses-Pyrénées—all located further from the capital of France, away from the central government troubles.[13]

Many individuals who were conscripted by the French deserted, fleeing from their duty of fighting for France without permission, in hopes of never getting caught. There were rough estimates to the number of individuals that deserted during the time of the Levée en Masse, but due to many factors, like the inability to manage and keep track of all the armies or differentiating between men with similar names, the exact number is unclear.[13] In 1800, the Minister of War (Carnot) reported that there were 175,000 deserters based on the number of individuals that sought the benefits following the amnesty put in place.[13] Similarly to how the proportions of males that were sent varied depending on what region they lived in, the same applied for deserters.

The historian Hargenvillier produced a detailed statistical breakdown of the percentage of desertions that flanked that specific department from 1798 to 1804.[13] In hopes of showing that like the previous levées that were proposed by the French government in an attempt to raise the number of troops, there were different reactions depending on region. There were regions where there was little to no resistance to the levée and no large amount of deserters, while other regions had nearly 60 percent deserters.[13]

Popular reaction

[edit]For all the rhetoric, the levée en masse was not popular; desertion and evasion were high. However, the effort was sufficient to turn the tide of the war, and there was no need for any further conscription until 1797, when a more permanent system of annual intakes was instituted. An effect of the levée en masse was the creation of a national army in France, made up of citizens, rather than an all-professional army, as was the standard practice of the time.

Its main result, protecting French borders against all enemies, surprised and shocked Europe. The levée en masse was also effective in that by putting on the field many men, even untrained, it required France's opponents to man all fortresses and expand their own standing armies, far beyond their capacity to pay professional soldiers.

The levée en masse also offered many opportunities for untrained people who could demonstrate their military proficiency, allowing the French army to build a strong officer and non-commissioned cadre.

Though not a novel idea—see for example thinkers as diverse as Plato, the political theorist Niccolo Machiavelli, and the lawyer and linguist Sir William Jones (who thought every adult male should be armed with a musket at public expense)—the actual practice of a levée en masse was rare before the French Revolution. The levée was a key development in modern warfare and would lead to steadily larger armies with each successive war, culminating in the enormous conflicts of World War I and World War II during the first half of the 20th century.

"Levée en masse" in the Third Reich

[edit]Hitler proclaimed a levée en masse in early January 1945 during the Battle of the Bulge at a meeting of his "inner circle" of Hitler with Martin Bormann, Joseph Goebbels, Wilhelm Keitel and Albert Speer, after it was apparent that the "breakthrough" had failed. Only Speer opposed total conscription, saying it would paralyse the weapons factories and effectively kill the war effort. Goebbels sneered: Then, Herr Speer, you bear the historic guilt for the loss of the war for the lack of a few hundred thousand soldiers.[14]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Cobb, Richard (1987). "Instrument of the Terror in the Departments, April 1793 to Flooreal Year II". The People's Armies: The Armees Revolutionnaires. New Haven: Yale UP.

- Forrest, Alan. The Legacy of the French Revolutionary Wars: The Nation-in-Arms in French Republican Memory (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

- Forrest, Alan (1990). The Soldiers of the French Revolution. Durham: Duke UP.

- Griffith, Paddy (1998). The Art of War of Revolutionary France: 1798–1802. London: Greenhill.

Sources

[edit]- ^ Schivelbusch, W. 2004, The Culture of Defeat, London: Granta Books, p. 8

- ^ Perry, Marvin, Joseph R. Peden, and Theodore H. Von Laue. "The Jacobin Regime." Sources of the Western Tradition: From the Renaissance to the Present. 4th ed. Vol. 2. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999. 108. Print. Sources of the Western Tradition.

- ^ Catherwood, Christopher; Horvitz, Leslie Alan (2006). Encyclopedia of War Crimes and Genocide. p. 279.

A levée does not refer to an uprising by people against its own government but instead entails organized resistance against an invader. Levée en masse implies that the population takes up arms already in its possession and that this uprising…

- ^ Alan Forrest, The Legacy of the French Revolutionary Wars: The Nation-in-Arms in French Republican Memory (2009).

- ^ a b c Blanning, T.C.W (1996). The French Revolutionary Wars 1787–1802. London: St. Martin's Press. p. 83.

- ^ a b Blanning, T.C.W (1996). The French Revolutionary Wars 1787–1802. London: St. Martin's Press. pp. 91–92.

- ^ James Maxwell Anderson (2007). Daily Life During the French Revolution. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-313-33683-6.

- ^ Lytle, Scott (1958). "Robespierre, Danton, and the Levée En Masse". The Journal of Modern History. 30 (4): 333. doi:10.1086/238263. S2CID 144759572.

- ^ Forrest, Alan (1 March 2004). "L'armée de l'an II : la levée en masse et la création d'un mythe républicain". Annales historiques de la Révolution française (in French) (335): 111–130. doi:10.4000/ahrf.1385. ISSN 0003-4436.

- ^ Stewart, John Hall (1951). "French military". A Documentary Survey of the French Revolution (8th ed.). New York: Macmillan. pp. 472–474.

- ^ Brown, Howard G. (1995). War, Revolution, and the Bureaucratic State. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 35.

- ^ a b Blanning, Timothy C. W. (1996). The French Revolutionary Wars: 1787–1802. London: St. Martin's Press. pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Forrest, Alan (1989). Conscripts and Deserters. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 32–70.

- ^ Tucker-Jones, Anthony (2022). Hitler's Winter: The German Battle of the Bulge. Oxford, UK: Osprey. p. 258. ISBN 978-1-4728-4739-3.