James Baldwin

James Baldwin | |

|---|---|

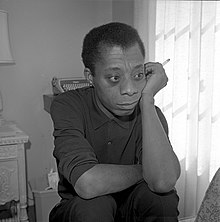

Baldwin in 1969 | |

| Born | James Arthur Jones August 2, 1924 New York, NY, U.S. |

| Died | December 1, 1987 (aged 63) Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France |

| Resting place | Ferncliff Cemetery, Westchester County, New York |

| Occupation |

|

| Education | DeWitt Clinton High School |

| Genre | |

| Years active | 1947–1985 |

| Notable works |

|

James Arthur Baldwin (né Jones; August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987) was an African-American writer and civil rights activist who garnered acclaim for his essays, novels, plays, and poems. His 1953 novel Go Tell It on the Mountain has been ranked by Time magazine as one of the top 100 English-language novels.[1] His 1955 essay collection Notes of a Native Son helped establish his reputation as a voice for human equality.[2] Baldwin was an influential public figure and orator, especially during the civil rights movement in the United States.[3][4][5]

Baldwin's fiction posed fundamental personal questions and dilemmas amid complex social and psychological pressures. Themes of masculinity, sexuality, race, and class intertwine to create intricate narratives that influenced both the civil rights movement and the gay liberation movement in mid-twentieth century America. His protagonists are often but not exclusively African-American; gay and bisexual men feature prominently in his work (as in his 1956 novel Giovanni's Room). His characters typically face internal and external obstacles in their search for self- and social acceptance.[6]

Baldwin's work continues to influence artists and writers. His unfinished manuscript Remember This House was expanded and adapted as the 2016 documentary film I Am Not Your Negro, winning the BAFTA Award for Best Documentary. His 1974 novel If Beale Street Could Talk was adapted into a 2018 film of the same name, which earned widespread praise.

Early life

[edit]Birth and family

[edit]Baldwin was born as James Arthur Jones to Emma Berdis Jones on August 2, 1924 at Harlem Hospital in New York City.[7] Born on Deal Island, Maryland in 1903,[8] Emma Jones was one of many who fled racial segregation and discrimination in the South during the Great Migration. She arrived in Harlem, New York when she was 19 years old.[9] Baldwin was born out of wedlock there. Jones never revealed to him who his biological father was.[9]

Jones originally undertook to care for her son as a single mother.[10] However, in 1927, Jones married David Baldwin, a laborer and Baptist preacher.[11] David Baldwin was born in Bunkie, Louisiana and preached in New Orleans, but left the South for Harlem in 1919.[11][a] How David and Emma met is uncertain, but in James Baldwin's semi-autobiographical Go Tell It on the Mountain, the characters based on the two are introduced by the man's sister.[12] Emma Baldwin and David Baldwin had eight children in sixteen years—George, Barbara, Wilmer, David Jr. (named for James's stepfather and deceased half-brother), Gloria, Ruth, Elizabeth, and Paula.[13] James took his stepfather's last name.[9] James rarely wrote or spoke of his mother. When he did, he made it clear that he admired and loved her, often through reference to her loving smile.[14]: 20 James moved several times while young but always within Harlem.[15] At the time, Harlem was still a mixed-race area of the city in the incipient days of the Great Migration.[16]

James Baldwin did not know exactly how old his stepfather was, but it is clear that he was much older than Emma; indeed, he may have been born before the Emancipation in 1863.[17] David's mother, Barbara, was born enslaved and lived with the Baldwins in New York before her death when James was seven years old.[17] David also had a light-skinned half-brother fathered by his mother's erstwhile enslaver[17] and a sister named Barbara, whom James and others in the family called "Taunty".[18] David's father was born a slave.[9] David had been married earlier and had a daughter, who was as old as Emma and at least two sons―David, who died while in jail, and Sam, who was eight years James' senior. Sam lived with the Baldwins for a time and once saved James from drowning.[14]: 7 [17]

James Baldwin referred to his stepfather simply as "father" throughout his life,[11] but David Sr. and James had an extremely difficult relationship and nearly resorted to physical fights on several occasions.[14]: 18 [b] "They fought because James read books, because he liked movies, because he had white friends", all of which, David Baldwin thought, threatened James's "salvation".[20] According to one biographer, David Baldwin also hated white people and "his devotion to God was mixed with a hope that God would take revenge on them for him."[21][c] During the 1920s and 1930s, David worked at a soft-drink bottling factory,[16] although he was eventually laid off from the job. As his anger and hatred eventually tainted his sermons, he was less in demand as a preacher. David sometimes took out his anger on his family and the children were afraid of him, though this was to some degree balanced by the love lavished on them by their mother.[23]

David Baldwin grew paranoid near the end of his life.[24] He was committed to a mental asylum in 1943 and died of tuberculosis on July 29 of that year, the same day Emma had their last child, Paula.[25] James, at his mother's urging, visited his dying stepfather the day before[26] and came to something of a posthumous reconciliation with him in his essay, "Notes of a Native Son." In the essay he wrote, "in his outrageously demanding and protective way, he loved his children, who were black like him and menaced like him".[27] David Baldwin's funeral was held on James' 19th birthday, around the same time that the Harlem riot began.[22]

As the oldest child, James Baldwin worked part-time from an early age to help support his family. He was molded not only by the difficult relationships in his own household but by the impacts of the poverty and discrimination he saw all around him. As he grew up, friends he sat next to in church turned to drugs, crime, or prostitution. In what biographer Anna Malaika Tubbs found to be not only a commentary on his own life but on the entire Black experience in America, Baldwin wrote, "I never had a childhood... I did not have any human identity... I was born dead."[28]

Education and preaching

[edit]Baldwin wrote comparatively little about events at school.[29] At five years of age, he was enrolled at Public School 24 (P.S. 24) on 128th Street in Harlem.[29] The principal of the school was Gertrude E. Ayer, the first Black principal in the city. She and some of Baldwin's teachers recognized his brilliance early on[30] and encouraged his research and writing pursuits.[31] Ayer stated that Baldwin derived his writing talent from his mother, whose notes to school were greatly admired by the teachers, and that her son also learned to write like an angel, albeit an avenging one.[32] By fifth grade, not yet a teenager, Baldwin had read some of Fyodor Dostoyevsky's works, Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, and Charles Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities (which gave him a lifelong interest in the work of Dickens).[33][21] Baldwin wrote a song that earned praise from New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia in a letter that La Guardia sent to him.[33] Baldwin also won a prize for a short story that was published in a church newspaper.[33] His teachers recommended that he go to a public library on 135th Street in Harlem, a place that became his sanctuary. Baldwin would request on his deathbed that his papers and effects be deposited there.[33]

It was at P.S. 24 that Baldwin met Orilla "Bill" Miller, a young white schoolteacher from the Midwest whom Baldwin named as one of the reasons that he "never really managed to hate white people".[34][d] Among other outings, Miller took Baldwin to see an all-Black rendition of Orson Welles's take on Macbeth at the Lafayette Theatre, from which flowed Baldwin's lifelong desire to succeed as a playwright.[38][e] David was reluctant to let his stepson go to the theatre, because he saw the stage as sinful and was suspicious of Miller. However, Baldwin's mother insisted, reminding his father of the importance of education.[39] Miller later directed the first play that Baldwin ever wrote.[40]

After P.S. 24, Baldwin entered Harlem's Frederick Douglass Junior High School.[29][f] There, Baldwin met two important influences.[42] The first was Herman W. "Bill" Porter, a Black Harvard graduate.[43] Porter was the faculty advisor to the school's newspaper, the Douglass Pilot, of which Baldwin would become the editor.[29] Porter took Baldwin to the library on 42nd Street to research a piece that would turn into Baldwin's first published essay titled "Harlem—Then and Now", which appeared in the autumn 1937 issue of the Douglass Pilot.[44] The second of these influences from his time at Frederick Douglass Junior High School was Countee Cullen, the renowned poet of the Harlem Renaissance.[45] Cullen taught French and was a literary advisor in the English department.[29] Baldwin later remarked that he "adored" Cullen's poetry, and his dream to live in France was sparked by Cullen's early impression on him.[43] Baldwin graduated from Frederick Douglass Junior High in 1938.[43][g]

In 1938, Baldwin applied to and was accepted at De Witt Clinton High School in the Bronx, a predominantly white and Jewish school, from where he matriculated that fall.[47] He worked on the school's magazine, the Magpie with Richard Avedon, who went on to become a noted photographer, and Emile Capouya and Sol Stein, who would both become renowned publishers.[47] Baldwin did interviews and editing at the magazine and published a number of poems and other writing.[48] He completed his high school diploma at De Witt Clinton in 1941.[49] Baldwin's yearbook listed his career ambition as "novelist-playwright", and his motto in the yearbook was: "Fame is the spur and—ouch!"[49]

Uncomfortable with his discovery during his high school years that he was attracted to men rather than women, Baldwin sought refuge in religion.[50] He joined the now-demolished Mount Calvary of the Pentecostal Faith Church on Lenox Avenue in 1937. He then followed Mount Calvary's preacher, Bishop Rose Artemis Horn (who was affectionately known as Mother Horn) when she left to preach at Fireside Pentecostal Assembly.[51] At the age of 14, "Brother Baldwin", as he was called, first took to Fireside's altar, and it was at Fireside Pentecostal, during his mostly extemporaneous sermons, that Baldwin "learned that he had authority as a speaker and could do things with a crowd."[52] He delivered his final sermon at Fireside Pentecostal in 1941.[52] Baldwin wrote in the essay "Down at the Cross" that the church "was a mask for self-hatred and despair ... salvation stopped at the church door".[53] He recalled a rare conversation with David Baldwin "in which they had really spoken to one another", during which his stepfather asked: "You'd rather write than preach, wouldn't you?"[53]

Later years in New York

[edit]Baldwin left school in 1941 in order to earn money to help support his family. He secured a job helping to build a United States Army depot in New Jersey.[54] In the middle of 1942, Emile Capouya helped Baldwin get a job laying tracks for the military in Belle Mead, New Jersey.[55] The two lived in Rocky Hill and commuted to Belle Mead.[55] In Belle Mead, Baldwin experienced prejudice that deeply frustrated and angered him and that he cited as the partial cause of his later emigration out of America.[56] Baldwin's fellow white workmen, who mostly came from the South, derided him for what they saw as his "uppity" ways, his sharp, ironic wit and his lack of "respect".[55]

In an incident that Baldwin described in his essay "Notes of a Native Son", he went to a restaurant in Princeton called the Balt where, after a long wait, Baldwin was told that "colored boys" were not served there.[55] Then, on his last night in New Jersey, in another incident also memorialized in "Notes of a Native Son", Baldwin and a friend went to a diner after a movie, only to be told that Black people were not served there.[57] Infuriated, he went to another restaurant, expecting to be denied service once again.[57] When that denial of service came, humiliation and rage overcame Baldwin and he hurled the nearest object at hand—a water mug—at the waitress, missing her and shattering the mirror behind her.[58] Baldwin and his friend narrowly escaped.[58]

During these years, Baldwin was torn between his desire to write and his need to provide for his family. He took a succession of menial jobs and feared that he was becoming like his stepfather, who had been unable to provide properly for his family.[59] Fired from the track-laying job, Baldwin returned to Harlem in June 1943 to live with his family after taking a meat-packing job.[58] He lost the meat-packing job too, after falling asleep at the plant.[22] He became listless and unstable, drifting from one odd job to the next.[60] Baldwin drank heavily and endured the first of his nervous breakdowns.[61]

Beauford Delaney helped Baldwin cast off his melancholy.[61] During the year before he left De Witt Clinton, and at Capuoya's urging, Baldwin had met Delaney, a modernist painter, in Greenwich Village.[62] Delaney would become Baldwin's long-time friend and mentor, and helped demonstrate to Baldwin that a Black man could make his living in art.[62] Moreover, when World War II bore down on the United States during the winter after Baldwin left De Witt Clinton, the Harlem that Baldwin knew was atrophying—no longer the bastion of a Renaissance, the community grew more economically isolated, and he considered his prospects there to be bleak.[63] This led him to move to Greenwich Village, a place that had fascinated him since at least the age of 15.[63]

Baldwin lived in several locations in Greenwich Village, first with Delaney, then with a scattering of other friends.[64] He took a job at the Calypso Restaurant, an unsegregated eatery famous for the parade of prominent Black people who dined there. At the Calypso, Baldwin worked under Trinidadian restaurateur Connie Williams. During this time, Baldwin continued to explore his sexuality, coming out to Capouya and another friend, and to frequent Calypso guest, Stan Weir.[65] Baldwin also had numerous one-night stands with various men, and several relationships with women.[65] His major love during his Village years was an ostensibly straight Black man named Eugene Worth.[66] Worth introduced Baldwin to the Young People's Socialist League and Baldwin became a Trotskyist for a brief period.[66] Baldwin never expressed his desire for Worth, and Worth died by suicide after jumping from the George Washington Bridge in 1946.[66][h] In 1944, Baldwin met Marlon Brando, to whom he was also attracted, at a theater class at The New School.[66] The two became fast friends, a friendship that endured through the Civil Rights Movement and long after.[66] In 1945, Baldwin started a literary magazine called The Generation with Claire Burch, who was married to Brad Burch, Baldwin's classmate from De Witt Clinton.[67] Baldwin's relationship with the Burches soured in the 1950s but was resurrected towards the end of his life.[68]

Near the end of 1945, Baldwin met Richard Wright, who had published the novel Native Son several years earlier.[69] Baldwin's main objective for that initial meeting was to interest Wright in an early manuscript of what would later become Go Tell It On The Mountain, but that was at the time titled "Crying Holy".[70] Wright liked the manuscript and encouraged his editors to consider Baldwin's work, but an initial $500 advance from Harper & Brothers was dissipated with no book to show for the money, and Harper eventually declined to publish the book at all.[71] Nonetheless, Baldwin regularly sent letters to Wright in the subsequent years and would reunite with Wright in Paris, France, in 1948 (though their relationship took a turn for the worse soon after the Paris reunion).[72]

During his Village years, Baldwin made a number of connections in New York's liberal literary establishment, primarily through Worth: Sol Levitas at The New Leader magazine, Randall Jarrell at The Nation, Elliot Cohen and Robert Warshow at Commentary, and Philip Rahv at Partisan Review.[73] Baldwin wrote many reviews for The New Leader, but was published for the first time in The Nation in a 1947 review of Maxim Gorki's Best Short Stories.[73] Only one of Baldwin's reviews from this era made it into his later essay collection The Price of the Ticket: a sharply ironic assay of Ross Lockridge's Raintree Countree that Baldwin wrote for The New Leader.[73] Baldwin's first essay, "The Harlem Ghetto", was published a year later in Commentary and explored anti-Semitism among Black Americans.[73] His conclusion was that Harlem was a parody of white America, with white American anti-Semitism included.[73] Jewish people were also the main group of white people that Black Harlem dwellers met, so Jews became a kind of synecdoche for all that the Black people in Harlem thought of white people.[74] Baldwin published his second essay in The New Leader, riding a mild wave of excitement over "Harlem Ghetto": in "Journey to Atlanta", Baldwin uses the diary recollections of his younger brother David, who had gone to Atlanta, Georgia, as part of a singing group, to unleash a lashing of irony and scorn on the South, white radicals, and ideology itself.[75] This essay, too, was well received.[76]

Baldwin tried to write another novel, Ignorant Armies, plotted in the vein of Native Son with a focus on a scandalous murder, but no final product materialised.[77] Baldwin spent two months during the summer of 1948 at Shanks Village, a writer's colony in Woodstock, New York. He then published his first work of fiction, a short story called "Previous Condition", in the October 1948 issue of Commentary magazine, about a 20-something Black man who is evicted from his apartment—the apartment being a metaphor for white society.[78]

Career

[edit]Life in Paris (1948–1957)

[edit]Disillusioned by the reigning prejudice against Black people in the United States, and wanting to gain external perspectives on himself and his writing, Baldwin settled in Paris, France, at the age of 24. Baldwin did not want to be read as "merely a Negro; or, even, merely a Negro writer."[79] He also hoped to come to terms with his sexual ambivalence and escape from the hopelessness to which many young African-American men like himself succumbed.[80]

In 1948, Baldwin received a $1,500 grant (equivalent to $19,022 in 2023)[81] from a Rosenwald Fellowship[82] in order to produce a book of photographs and essays that was to be both a catalog of churches and an exploration of religiosity in Harlem. Baldwin worked with a photographer friend named Theodore Pelatowski, whom Baldwin met through Richard Avedon.[83] Although the book (titled Unto the Dying Lamb) was never finished,[83] the Rosenwald funding did allow Baldwin to realise his long-standing ambition of moving to France.[84] After saying his goodbyes to his mother and his younger siblings, with forty dollars to his name, Baldwin flew from New York to Paris on November 11, 1948.[84] He gave most of the scholarship funds to his mother.[85] Baldwin would later give various explanations for leaving America—sex, Calvinism, an intense sense of hostility which he feared would turn inward—but, above all, was the problem of race, which, throughout his life, had exposed him to a lengthy catalog of humiliations.[86] He hoped for a more peaceable existence in Paris.[87]

In Paris, Baldwin was soon involved in the cultural radicalism of the Left Bank. He started to publish his work in literary anthologies, notably Zero[88] which was edited by his friend Themistocles Hoetis and which had already published essays by Richard Wright.

Baldwin spent nine years living in Paris, mostly in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, with various excursions to Switzerland, Spain, and back to the United States.[89] Baldwin's time in Paris was itinerant: he stayed with various friends around the city and in various hotels. Most notable of these lodgings was Hôtel Verneuil, a hotel in Saint-Germain that had collected a motley crew of struggling expatriates, mostly writers.[90] This Verneuil circle spawned numerous friendships that Baldwin relied upon in rough periods.[90] He was also extremely poor during his time in Paris, with only momentary respites from that condition.[91] In his early years in Saint-Germain, he met Otto Friedrich, Mason Hoffenberg, Asa Benveniste, Themistocles Hoetis, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Max Ernst, Truman Capote, and Stephen Spender, among many others.[92] Baldwin also met Lucien Happersberger, a Swiss boy, 17 years old at the time of their first meeting, who came to France in search of excitement.[93] Happersberger and Baldwin began to bond for the next few years, eventually becoming his intimate partner and he became Baldwin's near-obsession for some time afterward. Baldwin and Happersberger remained friends for the next thirty-nine years.[94][i] Even though his time in Paris was not easy, Baldwin escaped from the aspects of American life that outraged him the most—especially the "daily indignities of racism."[87] According to one biographer: "Baldwin seemed at ease in his Paris life; Jimmy Baldwin the aesthete and lover reveled in the Saint-Germain ambiance."[95]

During his early years in Paris, prior to the publication of Go Tell It on the Mountain in 1953, Baldwin wrote several notable works. "The Negro in Paris", first published in The Reporter, explored Baldwin's perception of an incompatibility between Black Americans and Black Africans in Paris, because Black Americans had faced a "depthless alienation from oneself and one's people" that was mostly unknown to Parisian Africans.[96] He also wrote "The Preservation of Innocence", which traced the violence against homosexuals in American life back to the protracted adolescence of America as a society.[97] In the magazine Commentary, he published "Too Little, Too Late", an essay about Black American literature, and he also published "The Death of the Prophet", a short story that grew out of Baldwin's earlier writings of Go Tell It on The Mountain. In the latter work, Baldwin employs a character named Johnnie to trace his bouts of depression back to his inability to resolve the questions of filial intimacy raised by his relationship with his stepfather.[98] In December 1949, Baldwin was arrested and jailed for receiving stolen goods after an American friend brought him bedsheets that the friend had taken from another Paris hotel.[99] When the charges were dismissed several days later, to the laughter of the courtroom, Baldwin wrote of the experience in his essay "Equal in Paris", also published in Commentary in 1950.[99] In the essay, he expressed his surprise and his bewilderment at how he was no longer a "despised black man", instead, he was simply an American, no different from the white American friend who stole the sheet and was arrested with him.[99]

During his Paris years, Baldwin also published two of his three scathing critiques of Richard Wright—"Everybody's Protest Novel" in 1949 and "Many Thousands Gone" in 1951. Baldwin criticizes Wright's work for being protest literature, which Baldwin despised because it is "concerned with theories and with the categorization of human beings, and however brilliant the theories or accurate the categorizations, they fail because they deny life."[96] Protest writing cages humanity, but, according to Baldwin, "only within this web of ambiguity, paradox, this hunger, danger, darkness, can we find at once ourselves and the power that will free us from ourselves."[96] Baldwin took Wright's Native Son and Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, both erstwhile favorites of Baldwin's, as paradigmatic analysis examples of the protest novel's problem.[96] The treatment of Wright's character Bigger Thomas by socially earnest white people near the end of Native Son was, for Baldwin, emblematic of white Americans' presumption that for Black people "to become truly human and acceptable, [they] must first become like us. This assumption once accepted, the Negro in America can only acquiesce in the obliteration of his own personality."[100] In these two essays, Baldwin came to articulate what would become a theme of his work: that white racism toward Black Americans was refracted through self-hatred and self-denial—"One may say that the Negro in America does not really exist except in the darkness of [white] minds. [...] Our dehumanization of the Negro then is indivisible from our dehumanization of ourselves."[100][j] Baldwin's relationship with Wright was tense but cordial after the essays, although Baldwin eventually ceased to regard Wright as a mentor.[101] Meanwhile, "Everybody's Protest Novel" had earned Baldwin the label "the most promising young Negro writer since Richard Wright."[102]

Beginning in the winter of 1951, Baldwin and Happersberger took several trips to Loèches-les-Bains in Switzerland, where Happersberger's family owned a small chateau.[103] By the time of the first trip, Happersberger had then entered a heterosexual relationship but grew worried for his friend Baldwin and offered to take Baldwin to the Swiss village.[103] Baldwin's time in the village gave form to his essay "Stranger in the Village", published in Harper's Magazine in October 1953.[104] In that essay, Baldwin described some unintentional mistreatment and offputting experiences at the hands of Swiss villagers who possessed a racial innocence which few Americans could attest to.[103] Baldwin explored how the bitter history which was shared by Black and white Americans had formed an indissoluble web of relations that changed the members of both races: "No road whatever will lead Americans back to the simplicity of this European village where white men still have the luxury of looking on me as a stranger."[104]

Beauford Delaney's arrival in France in 1953 marked "the most important personal event in Baldwin's life" that year.[105] Around the same time, Baldwin's circle of friends shifted away from primarily white bohemians toward a coterie of Black American expatriates: Baldwin grew close to dancer Bernard Hassell; spent significant amounts of time at Gordon Heath's club in Paris; regularly listened to Bobby Short and Inez Cavanaugh's performances at their respective haunts around the city; met Maya Angelou during her European tour of Porgy and Bess; and occasionally met with writers Richard Gibson and Chester Himes, composer Howard Swanson, and even Richard Wright.[106] In 1954, Baldwin accepted a fellowship at the MacDowell writer's colony in New Hampshire to support the writing of a new novel and he also won a Guggenheim Fellowship.[107] Also in 1954, Baldwin published the three-act play The Amen Corner which features the preacher Sister Margaret—a fictionalized Mother Horn from Baldwin's time at Fireside Pentecostal—who struggles with a difficult inheritance and with alienation from herself and her loved ones on account of her religious fervor.[108] Baldwin spent several weeks in Washington, D.C., and particularly around Howard University while he collaborated with Owen Dodson for the premiere of The Amen Corner. Baldwin returned to Paris in October 1955.[109]

Baldwin decided that he would return to the United States in 1957, so in early 1956, he decided to enjoy what was to be his last year in France.[110] He became friends with Norman and Adele Mailer, was recognized by the National Institute of Arts and Letters with a grant, and he was set to publish Giovanni's Room.[111] Nevertheless, Baldwin sank deeper into an emotional wreckage. In the summer of 1956—after a seemingly failed affair with a Black musician named Arnold, Baldwin's first serious relationship since Happersberger—Baldwin overdosed on sleeping pills during a suicide attempt.[112] He regretted the attempt almost instantly and he called a friend who had him regurgitate the pills before the doctor arrived.[112] Baldwin went on to attend the Congress of Black Writers and Artists in September 1956, a conference which he found disappointing in its perverse reliance on European themes while nonetheless purporting to extol African originality.[113]

Literary career

[edit]Baldwin's first published work, a review of the writer Maxim Gorky, appeared in The Nation in 1947.[114][115] He continued to publish there at various times in his career and was serving on its editorial board at the time of his death in 1987.[115]

1950s

[edit]In 1953, Baldwin published his first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, a semi-autobiographical bildungsroman. He began writing it when he was 17 and first published it in Paris. His first collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son appeared two years later. He continued to experiment with literary forms throughout his career, publishing poetry and plays as well as the fiction and essays for which he was known.

Baldwin's second novel, Giovanni's Room, caused great controversy when it was first published in 1956 due to its explicit homoerotic content.[116] Baldwin again resisted labels with the publication of this work.[117] Despite the reading public's expectations that he would publish works dealing with African-American experiences, Giovanni's Room is predominantly about white characters.[117]

Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953)

[edit]Baldwin sent the manuscript for Go Tell It on the Mountain from Paris to New York publishing house Alfred A. Knopf on February 26, 1952, and Knopf expressed interest in the novel several months later.[118] To settle the terms of his association with Knopf, Baldwin sailed back to the United States in April 1952 on the SS Île de France, where Themistocles Hoetis and Dizzy Gillespie were coincidentally also voyaging—his conversations with both on the ship were extensive.[118] After his arrival in New York, Baldwin spent much of the next three months with his family, whom he had not seen in almost three years.[119] Baldwin grew particularly close to his younger brother, David Jr., and served as best man at David's wedding on June 27.[118] Meanwhile, Baldwin agreed to rewrite parts of Go Tell It on the Mountain in exchange for a $250 advance ($2,868 today) and a further $750 ($8,605 today) paid when the final manuscript was completed.[119] When Knopf accepted the revision in July, they sent the remainder of the advance, and Baldwin was soon to have his first published novel.[120] In the interim, Baldwin published excerpts of the novel in two publications: one excerpt was published as "Exodus" in American Mercury and the other as "Roy's Wound" in New World Writing.[120] Baldwin set sail back to Europe on August 28 and Go Tell It on the Mountain was published in May 1953.[120]

Go Tell It on the Mountain was the product of years of work and exploratory writing since his first attempt at a novel in 1938.[121] In rejecting the ideological manacles of protest literature and the presupposition he thought inherent to such works that "in Negro life there exists no tradition, no field of manners, no possibility of ritual or intercourse", Baldwin sought in Go Tell It on the Mountain to emphasize that the core of the problem was "not that the Negro has no tradition but that there has as yet arrived no sensibility sufficiently profound and tough to make this tradition articulate."[122] Baldwin biographer David Leeming draws parallels between Go Tell It on the Mountain and James Joyce's 1916 A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: to "encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race."[123] Baldwin himself drew parallels between Joyce's flight from his native Ireland and his own run from Harlem, and Baldwin read Joyce's tome in Paris in 1950, however, in Baldwin's Go Tell It on the Mountain, it would be the Black American "uncreated conscience" at the heart of the project.[124]

The novel is a bildungsroman that explores the inward struggles of protagonist John Grimes, the illegitimate son of Elizabeth Grimes, to claim his own soul as it lies on the "threshing floor"—a clear allusion to another John: the Baptist, born of another Elizabeth.[121] John's struggle is a metaphor for Baldwin's own struggle between escaping the history and heritage that made him, awful though it may be, and plunging deeper into that heritage, to the bottom of his people's sorrows, before he can shrug off his psychic chains, "climb the mountain", and free himself.[121] John's family members and most of the characters in the novel are blown north in the winds of the Great Migration in search of the American Dream and all are stifled.[125] Florence, Elizabeth, and Gabriel are denied love's reach because racism assured that they could not muster the kind of self-respect that love requires.[125] Racism drives Elizabeth's lover, Richard, to suicide—Richard will not be the last Baldwin character to die thus for that same reason.[121] Florence's lover Frank is destroyed by searing self-hatred of his own Blackness.[121] Gabriel's abuse of the women in his life is downstream from his society's emasculation of him, with mealy-mouthed religiosity only a hypocritical cover.[121]

The phrase "in my father's house" and various similar formulations appear throughout Go Tell It on the Mountain and was even an early title for the novel.[122] The house is a metaphor at several levels of generality: for his own family's apartment in Harlem, for Harlem taken as a whole, for America and its history, and for the "deep heart's core".[122] John's departure from the agony that reigned in his father's house, particularly the historical sources of the family's privations, came through a conversion experience.[125] "Who are these? Who are they?" John cries out when he sees a mass of faces as he descends to the threshing floor: 'They were the despised and rejected, the wretched and the spat upon, the earth's offscouring; and he was in their company, and they would swallow up his soul."[126] John wants desperately to escape the threshing floor, but "[t]hen John saw the Lord" and "a sweetness" filled him.[126] The midwife of John's conversion is Elisha, the voice of love that had followed him throughout the experience, and whose body filled John with "a wild delight".[126] Thus comes the wisdom that would define Baldwin's philosophy: per biographer David Leeming: "salvation from the chains and fetters—the self-hatred and the other effects—of historical racism could come only from love."[126]

Notes of a Native Son (1955)

[edit]Baldwin's friend from high school, Sol Stein, encouraged Baldwin to publish an essay collection reflecting on his work thus far.[127] Originally, Baldwin was reluctant, saying he was "too young to publish my memoirs."[127] but he nevertheless produced a collection, Notes of a Native Son, that was published in 1955.[127] The book contained practically all of the major themes that run through his work: searching for self when racial myths cloud reality; accepting an inheritance ("the conundrum of color is the inheritance of every American"); claiming a birthright ("my birthright was vast, connecting me to all that lives, and to everyone, forever"); the artist's loneliness; love's urgency.[128] All the essays in Notes were published between 1948 and 1955 in Commentary, The New Leader, Partisan Review, The Reporter, and Harper's Magazine.[129] The essays rely on autobiographical detail to convey Baldwin's arguments, as all of Baldwin's work does.[129] Notes was Baldwin's first introduction to many white Americans and it became their reference point for his work: Baldwin was often asked: "Why don't you write more essays like the ones in Notes of a Native Son?"[129] The collection's title alludes to both Richard Wright's Native Son and the work of one of Baldwin's favorite writers, Henry James's Notes of a Son and Brother.[130]

Notes of a Native Son is divided into three parts: the first part deals with Black identity as artist and human; the second part addresses Black life in America, including what is sometimes considered Baldwin's best essay, the titular "Notes of a Native Son"; the final part takes the expatriate's perspective, looking at American society from beyond its shores.[131] Part One of Notes features "Everybody's Protest Novel" and "Many Thousands Gone", along with "Carmen Jones: The Dark Is Light Enough", a 1955 review of Carmen Jones written for Commentary, in which Baldwin at once extols the sight of an all-Black cast on the silver screen and laments the film's myths about Black sexuality.[132] Part Two reprints "The Harlem Ghetto" and "Journey to Atlanta" as prefaces for "Notes of a Native Son". In "Notes of a Native Son", Baldwin attempts to come to terms with his racial and filial inheritances.[133] Part Three contains "Equal in Paris", "Stranger in the Village", "Encounter on the Seine", and "A Question of Identity". Writing from the expatriate's perspective, Part Three is the sector of Baldwin's corpus that most closely mirrors Henry James's methods: hewing out of one's distance and detachment from the homeland a coherent idea of what it means to be American.[133][k]

Throughout Notes, when Baldwin is not speaking in first-person, Baldwin takes the view of white Americans. For example, in "The Harlem Ghetto", Baldwin writes: "what it means to be a Negro in America can perhaps be suggested by the myths we perpetuate about him."[130] This earned some quantity of scorn from reviewers: in a review for The New York Times Book Review, Langston Hughes lamented that "Baldwin's viewpoints are half American, half Afro-American, incompletely fused."[130] Others were nonplussed by the handholding of white audiences, which Baldwin himself would criticize in later works.[130] Nonetheless, most acutely in this stage in his career, Baldwin wanted to escape the rigid categories of protest literature and he viewed adopting a white point-of-view as a good method of doing so.[130]

Giovanni's Room (1956)

[edit]Shortly after returning to Paris in 1956, Baldwin got word from Dial Press that Giovanni's Room had been accepted for publication.[134] The book was published that autumn.[135]

In the novel, the protagonist David is in Paris while his fiancée Hella is in Spain. David meets the titular Giovanni at a bar; the two grow increasingly intimate and David eventually finds his way to Giovanni's room. David is confused by his intense feelings for Giovanni and has sex with a woman in the spur of the moment to reaffirm his heterosexuality. Meanwhile, Giovanni begins to prostitute himself and finally commits a murder for which he is guillotined.[136] David's tale is one of love's inhibition: he cannot "face love when he finds it", writes biographer James Campbell.[137] The novel features a traditional theme: the clash between the constraints of puritanism and the impulse for adventure and the subsequent loss of innocence that results.[137]

The inspiration for the murder in the novel's plot is an event dating from 1943 to 1944. A Columbia University undergraduate named Lucien Carr murdered an older, homosexual man, David Kammerer, who made sexual advances on Carr.[138] The two were walking near the banks of the Hudson River when Kammerer made a pass at Carr, leading Carr to stab Kammerer and dump Kammerer's body in the river.[139] To Baldwin's relief, the reviews of Giovanni's Room were positive, and his family did not criticize the subject matter.[140]

Return to New York

[edit]Even from Paris, Baldwin was able to follow the emergence of the Civil Rights Movement in his homeland. In May 1954, the United States Supreme Court ordered schools to desegregate "with all deliberate speed"; in August 1955 the racist murder of Emmett Till in Money, Mississippi, and the subsequent acquittal of his killers were etched in Baldwin's mind until he wrote Blues for Mister Charlie; in December 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus; and in February 1956 Autherine Lucy was admitted to the University of Alabama before being expelled when whites rioted.[141] Meanwhile, Baldwin was increasingly burdened by the sense that he was wasting time in Paris.[134] Baldwin began planning a return to the United States in hopes of writing a biography of Booker T. Washington, which he then called Talking at the Gates. Baldwin also received commissions to write a review of Daniel Guérin's Negroes on the March and J. C. Furnas's Goodbye to Uncle Tom for The Nation, as well as to write about William Faulkner and American racism for the Partisan Review.[142]

The first project became "The Crusade of Indignation",[142] published in July 1956.[143] In it, Baldwin suggests that the portrait of Black life in Uncle Tom's Cabin "has set the tone for the attitude of American whites towards Negroes for the last one hundred years", and that, given the novel's popularity, this portrait has led to a unidimensional characterization of Black Americans that does not capture the full scope of Black humanity.[142] The second project turned into the essay "William Faulkner and Desegregation". The essay was inspired by Faulkner's March 1956 comment during an interview that he was sure to enlist himself with his fellow white Mississippians in a war over desegregation "even if it meant going out into the streets and shooting Negroes".[142] For Baldwin, Faulkner represented the "go slow" mentality on desegregation that tries to wrestle with the Southerner's peculiar dilemma: the South "clings to two entirely antithetical doctrines, two legends, two histories"; the southerner is "the proud citizen of a free society and, on the other hand, committed to a society that has not yet dared to free itself of the necessity of naked and brutal oppression."[142] Faulkner asks for more time but "the time [...] does not exist. [...] There is never time in the future in which we will work out our salvation."[142]

Baldwin initially intended to complete Another Country before returning to New York in the fall of 1957 but progress on the novel was slow, so he decided to go back to the United States sooner.[144][145] Beauford Delaney was particularly upset by Baldwin's departure. Delaney had started to drink heavily and entered the incipient stages of mental deterioration, including complaining about hearing voices.[144][l] Nonetheless, after a brief visit with Édith Piaf, Baldwin set sail for New York in July 1957.[144]

1960s

[edit]Baldwin's third and fourth novels, Another Country (1962) and Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone (1968), are sprawling, experimental works[146] dealing with Black and white characters, as well as with heterosexual, gay, and bisexual characters.[147] Baldwin completed Another Country during his first, two-month stay in Istanbul (which ends with the note, Istanbul, Dec. 10, 1961). This was to be the first of many stays in Istanbul during the 1960s.[148]

Baldwin's lengthy essay "Down at the Cross" (frequently called The Fire Next Time after the title of the 1963 book in which it was published)[149] similarly showed the seething discontent of the 1960s in novel form. The essay was originally published in two oversized issues of The New Yorker and landed Baldwin on the cover of Time magazine in 1963 while he was touring the South speaking about the restive Civil Rights Movement. Around the time of publication of The Fire Next Time, Baldwin became a known spokesperson for civil rights and a celebrity noted for championing the cause of Black Americans. He frequently appeared on television and delivered speeches on college campuses.[150] The essay talked about the uneasy relationship between Christianity and the burgeoning Black Muslim movement. After publication, several Black nationalists criticized Baldwin for his conciliatory attitude. They questioned whether his message of love and understanding would do much to change race relations in America.[150] The book was consumed by whites looking for answers to the question: What do Black Americans really want? Baldwin's essays never stopped articulating the anger and frustration felt by real-life Black Americans with more clarity and style than any other writer of his generation.[151]

In 1965, Baldwin participated in a much publicized debate with William F. Buckley, on the topic of whether the American dream had been achieved at the expense of African Americans. The debate took place in the UK at the Cambridge Union, historic debating society of the University of Cambridge. The spectating student body voted overwhelmingly in Baldwin's favor.[152][153]

1970s and 1980s

[edit]Baldwin's next book-length essay, No Name in the Street (1972), also discussed his own experience in the context of the later 1960s, specifically the assassinations of three of his personal friends: Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr.

Baldwin's writings of the 1970s and 1980s were largely overlooked by critics, although they have received increasing attention in recent years.[154] Several of his essays and interviews of the 1980s discuss homosexuality and homophobia with fervor and forthrightness.[150] Eldridge Cleaver's harsh criticism of Baldwin in Soul on Ice and elsewhere[155] and Baldwin's return to southern France contributed to the perception by critics that he was not in touch with his readership.[156][157][158] As he had been the leading literary voice of the civil rights movement, he became an inspirational figure for the emerging gay rights movement.[150] His two novels written in the 1970s, If Beale Street Could Talk (1974) and Just Above My Head (1979), stressed the importance of Black American families. He concluded his career by publishing a volume of poetry, Jimmy's Blues (1983), as well as another book-length essay, The Evidence of Things Not Seen (1985), an extended reflection on race inspired by the Atlanta murders of 1979–1981.

Saint-Paul-de-Vence

[edit]

Baldwin lived in France for most of his later life, using it as a base of operations for extensive international travel.[148][159][160] Baldwin settled in Saint-Paul-de-Vence in the south of France in 1970, in an old Provençal house beneath the ramparts of the famous village.[161] His house was always open to his friends, who frequently visited him while on trips to the French Riviera. American painter Beauford Delaney made Baldwin's house in Saint-Paul-de-Vence his second home, often setting up his easel in the garden. Delaney painted several colorful portraits of Baldwin. Fred Nall Hollis also befriended Baldwin during this time. Actors Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier were also regular guests.

Many of Baldwin's musician friends dropped in during the Jazz à Juan and Nice Jazz Festivals. They included Nina Simone, Josephine Baker (whose sister lived in Nice), Miles Davis, and Ray Charles.[162] In his autobiography, Miles Davis wrote:[163]

I'd read his books and I liked and respected what he had to say. As I got to know Jimmy we opened up to each other and became real great friends. Every time I went to southern France to play Antibes, I would always spend a day or two out at Jimmy's house in St. Paul de Vence. We'd just sit there in that great big beautiful house of his telling us all kinds of stories, lying our asses off.... He was a great man.

Baldwin learned to speak French fluently and developed friendships with French actor Yves Montand and French writer Marguerite Yourcenar, who translated Baldwin's play The Amen Corner into French.

Baldwin spent 17 years, until his death in 1987, in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, in the south-east between Nice and Cannes.[164] The years he spent there were also years of work. Sitting in front of his sturdy typewriter, he devoted his days to writing and to answering the huge amount of mail he received from all over the world. He wrote several of his last works in his house in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, including Just Above My Head in 1979 and Evidence of Things Not Seen in 1985. It was also in Saint-Paul-de-Vence that Baldwin wrote his famous "Open Letter to My Sister, Angela Y. Davis" in November 1970.[165][166]

His last novel, Harlem Quartet, was published in 1987.[167]

Death

[edit]

On December 1, 1987,[168][169][170][contradictory][171] Baldwin died from stomach cancer in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France.[172][173][174] He was buried at the Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, near New York City.[175]

Fred Nall Hollis took care of Baldwin on his deathbed. Nall had been friends with Baldwin from the early 1970s when Baldwin would buy him drinks at the Café de Flore. Nall recalled talking to Baldwin shortly before his death about racism in Alabama. In one conversation, Nall told Baldwin "Through your books you liberated me from my guilt about being so bigoted coming from Alabama and because of my homosexuality." Baldwin insisted: "No, you liberated me in revealing this to me."[176]

A few hours after his death, his novel Harlem Quartet, published earlier in the year, won the French-American Friendship Prize (having a week earlier lost out by one vote in Paris for the Prix Femina awarded to the best foreign novel of the year).[167]

At the time of Baldwin's death, he was working on an unfinished manuscript called Remember This House, a memoir of his personal recollections of civil rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.[177] Following his death, publishing company McGraw-Hill took the unprecedented step of suing his estate to recover the $200,000 advance they had paid him for the book, although the lawsuit was dropped by 1990.[177] The manuscript forms the basis for Raoul Peck's 2016 documentary film I Am Not Your Negro.[178]

Following Baldwin's death, a court battle was waged over the ownership of his home in France. Baldwin had been in the process of purchasing his house from his landlady, Jeanne Faure.[179] At the time of his death, Baldwin did not have full ownership of the home, and it was Mlle. Faure's intention that the home would stay in her family. His home, nicknamed "Chez Baldwin",[180] has been the center of scholarly work and artistic and political activism. The National Museum of African American History and Culture has an online exhibit titled "Chez Baldwin", which uses his historic French home as a lens to explore his life and legacy.[181] Magdalena J. Zaborowska's 2018 book, Me and My House: James Baldwin's Last Decade in France, uses photographs of his home and his collections to discuss themes of politics, race, queerness, and domesticity.[182]

Over the years, several efforts were initiated to save the house and convert it into an artist residency. None had the endorsement of the Baldwin estate. In February 2016, Le Monde published an opinion piece by Thomas Chatterton Williams, a contemporary Black American expatriate writer in France, which spurred a group of activists to come together in Paris.[183] In June 2016, American writer and activist Shannon Cain squatted at the house for 10 days in an act of political and artistic protest.[184][185] Les Amis de la Maison Baldwin,[186] a French organization whose initial goal was to purchase the house by launching a capital campaign funded by the U.S. philanthropic sector, grew out of this effort.[187] This campaign was unsuccessful without the support of the Baldwin Estate. Attempts to engage the French government in conservation of the property were dismissed by the mayor of Saint-Paul-de-Vence, Joseph Le Chapelain, whose statement to the local press claiming "nobody's ever heard of James Baldwin" mirrored that of Henri Chambon, the owner of the corporation that razed the house.[188][189] Construction was completed in 2019 on the apartment complex that now stands where Chez Baldwin once stood.

Themes

[edit]Struggle for self

[edit]In all of Baldwin's works, but particularly in his novels, the main characters are twined up in a "cage of reality" that sees them fighting for their soul against the limitations of the human condition or against their place at the margins of a society consumed by various prejudices.[190] Baldwin connects many of his main characters—John in Go Tell It On The Mountain, Rufus in Another Country, Richard in Blues for Mister Charlie, and Giovanni in Giovanni's Room—as sharing a reality of restriction: per biographer David Leeming, each is "a symbolic cadaver in the center of the world depicted in the given novel and the larger society symbolized by that world".[191] Each reaches for an identity within their own social environment, and sometimes—as in If Beale Street Could Talk's Fonny and Tell me How Long The Train's Been Gone's Leo—they find such an identity, imperfect but sufficient to bear the world.[191] The singular theme in the attempts of Baldwin's characters to resolve their struggle for themselves is that such resolution only comes through love.[191] Here is Leeming at some length:

Love is at the heart of the Baldwin philosophy. Love for Baldwin cannot be safe; it involves the risk of commitment, the risk of removing the masks and taboos placed on us by society. The philosophy applies to individual relationships as well as to more general ones. It encompasses sexuality as well as politics, economics, and race relations. And it emphasizes the dire consequences, for individuals and racial groups, of the refusal to love.

— David Adams Leeming, James Baldwin: A Biography[192]

Social and political activism

[edit]

Baldwin returned to the United States in the summer of 1957, while the civil rights legislation of that year was being debated in Congress. He had been powerfully moved by the image of a young girl, Dorothy Counts, braving a mob in an attempt to desegregate schools in Charlotte, North Carolina, and Partisan Review editor Philip Rahv had suggested he report on what was happening in the American South. Baldwin was nervous about the trip but he made it, interviewing people in Charlotte (where he met Martin Luther King Jr.), and Montgomery, Alabama. The result was two essays, one published in Harper's magazine ("The Hard Kind of Courage"), the other in Partisan Review ("Nobody Knows My Name"). Subsequent Baldwin articles on the movement appeared in Mademoiselle, Harper's, The New York Times Magazine, and The New Yorker, where in 1962 he published the essay that he called "Down at the Cross", and the New Yorker called "Letter from a Region of My Mind". Along with a shorter essay from The Progressive, the essay became The Fire Next Time.[193]: 94–99, 155–56

| External audio | |

|---|---|

While he wrote about the movement, Baldwin aligned himself with the ideals of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Joining CORE allowed him to travel across the South, lecturing on racial inequality. His insights into both the North and South gave him a unique perspective on the racial problems the United States was facing.

In 1963 he conducted a lecture tour of the South for CORE, traveling to Durham and Greensboro in North Carolina, and New Orleans. During the tour, he lectured to students, white liberals, and anyone else listening about his racial ideology, an ideological position between the "muscular approach" of Malcolm X and the nonviolent program of Martin Luther King Jr.[140] Baldwin expressed the hope that socialism would take root in the United States:[195]

It is certain, in any case, that ignorance, allied with power, is the most ferocious enemy justice can have.

- —James Baldwin

By the spring of 1963, the mainstream press began to recognize Baldwin's incisive analysis of white racism and his eloquent descriptions of the Negro's pain and frustration. In fact, Time featured Baldwin on the cover of its May 17, 1963, issue. "There is not another writer", said Time, "who expresses with such poignancy and abrasiveness the dark realities of the racial ferment in North and South."[196][193]: 175

In a cable Baldwin sent to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy during the Birmingham riot of 1963, Baldwin blamed the violence in Birmingham on the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, Mississippi Senator James Eastland, and President Kennedy for failing to use "the great prestige of his office as the moral forum which it can be." Attorney General Kennedy invited Baldwin to meet with him over breakfast, and that meeting was followed up with a second, when Kennedy met with Baldwin and others Baldwin had invited to Kennedy's Manhattan apartment. This meeting is discussed in Howard Simon's 1999 play, James Baldwin: A Soul on Fire. The delegation included Kenneth B. Clark, a psychologist who had played a key role in the Brown v. Board of Education decision; actor Harry Belafonte, singer Lena Horne, writer Lorraine Hansberry, and activists from civil rights organizations.[193]: 176–80 Although most of the attendees of this meeting left feeling "devastated", the meeting was an important one in voicing the concerns of the civil rights movement, and it provided exposure of the civil rights issue not just as a political issue but also as a moral issue.[197]

James Baldwin's FBI file contains 1,884 pages, collected from 1960 until the early 1970s.[198] During that era of surveillance of American writers, the FBI accumulated 276 pages on Richard Wright, 110 pages on Truman Capote, and just nine pages on Henry Miller.

Baldwin also made a prominent appearance at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963, with Belafonte and long-time friends Sidney Poitier and Marlon Brando.[199]

Baldwin's sexuality clashed with his activism. The civil rights movement was hostile to homosexuals.[200][201] The only overtly gay men in the movement were Baldwin and Bayard Rustin. Rustin and King were very close, as Rustin received credit for the success of the March on Washington. Many were bothered by Rustin's sexual orientation. King himself spoke on the topic of sexual orientation in a school editorial column during his college years, and in reply to a letter during the 1950s, where he treated it as a mental illness which an individual could overcome. King's key advisor, Stanley Levison, also stated that Baldwin and Rustin were "better qualified to lead a homo-sexual movement than a civil rights movement".[202] The pressure later resulted in King distancing himself from both men. Despite his enormous efforts within the movement, Baldwin was excluded from the inner circles of the civil rights movement because of his sexuality and was conspicuously not invited to speak at the March on Washington.[203]

At the time, Baldwin was neither in the closet nor open to the public about his sexual orientation. Although his novels, specifically Giovanni's Room and Just Above My Head, had openly gay characters and relationships, Baldwin himself never openly described his sexuality. In his book, Kevin Mumford points out how Baldwin went his life "passing as straight rather than confronting homophobes with whom he mobilized against racism".[204]

When the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing happened in Birmingham three weeks after the March on Washington, Baldwin called for a nationwide campaign of civil disobedience in response to this "terrifying crisis". He traveled to Selma, Alabama, where SNCC had organized a voter registration drive; he watched mothers with babies and elderly men and women standing in long lines for hours, as armed deputies and state troopers stood by—or intervened to smash a reporter's camera or use cattle prods on SNCC workers. After his day of watching, he spoke in a crowded church, blaming Washington—"the good white people on the hill". Returning to Washington, he told a New York Post reporter the federal government could protect Negroes—it could send federal troops into the South. He blamed the Kennedys for not acting.[193]: 191, 195–98 In March 1965, Baldwin joined marchers who walked 50 miles from Selma, Alabama (Selma to Montgomery Marches), to the capitol in Montgomery under the protection of federal troops.[193]: 236

Nonetheless, he rejected the label "civil rights activist", or that he had participated in a civil rights movement, instead agreeing with Malcolm X's assertion that if one is a citizen, one should not have to fight for one's civil rights. In a 1964 interview with Robert Penn Warren for the book Who Speaks for the Negro?, Baldwin rejected the idea that the civil rights movement was an outright revolution, instead calling it "a very peculiar revolution because it has to... have its aims the establishment of a union, and a... radical shift in the American mores, the American way of life... not only as it applies to the Negro obviously, but as it applies to every citizen of the country."[205] In a 1979 speech at UC Berkeley, Baldwin called it, instead, "the latest slave rebellion".[206]

In 1968, Baldwin signed the "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" pledge, vowing to refuse to make income tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.[207] He was also a supporter of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, which prompted the FBI to create a file on Baldwin.[208]

Inspiration and relationships

[edit]

A great influence on Baldwin was the painter Beauford Delaney. In The Price of the Ticket (1985), Baldwin describes Delaney as:

... the first living proof, for me, that a black man could be an artist. In a warmer time, a less blasphemous place, he would have been recognized as my teacher and I as his pupil. He became, for me, an example of courage and integrity, humility and passion. An absolute integrity: I saw him shaken many times and I lived to see him broken but I never saw him bow.

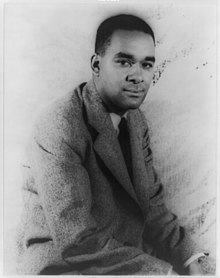

Later support came from Richard Wright, whom Baldwin called "the greatest black writer in the world". Wright and Baldwin became friends, and Wright helped Baldwin to secure the Eugene F. Saxton Memorial Foundation $500 fellowship.[209] Baldwin's essay "Notes of a Native Son" and his collection Notes of a Native Son allude to Wright's 1940 novel Native Son. In Baldwin's 1949 essay "Everybody's Protest Novel", however, he indicated that Native Son, like Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), lacked credible characters and psychological complexity, and the friendship between the two authors ended.[210] Interviewed by Julius Lester,[211] however, Baldwin explained: "I knew Richard and I loved him. I was not attacking him; I was trying to clarify something for myself."

In 1949, Baldwin met and fell in love with Lucien Happersberger, a boy aged 17, though Happersberger's marriage three years later left Baldwin distraught. When the marriage ended, they later reconciled, with Happersberger staying by Baldwin's deathbed at his house in Saint-Paul-de-Vence.[212] Happersberger died on August 21, 2010, in Switzerland.

Baldwin was a close friend of the singer, pianist, and civil rights activist Nina Simone. Langston Hughes, Lorraine Hansberry, and Baldwin helped Simone learn about the Civil Rights Movement. Baldwin also provided her with literary references influential on her later work. Baldwin and Hansberry met with Robert F. Kennedy, along with Kenneth Clark and Lena Horne and others in an attempt to persuade Kennedy of the importance of civil rights legislation.[213]

Baldwin influenced the work of French painter Philippe Derome, whom he met in Paris in the early 1960s. Baldwin also knew Marlon Brando, Charlton Heston, Billy Dee Williams, Huey P. Newton, Nikki Giovanni, Jean-Paul Sartre, Jean Genet (with whom he campaigned on behalf of the Black Panther Party), Lee Strasberg, Elia Kazan, Rip Torn, Alex Haley, Miles Davis, Amiri Baraka, Martin Luther King Jr., Dorothea Tanning, Leonor Fini, Margaret Mead, Josephine Baker, Allen Ginsberg, Chinua Achebe, and Maya Angelou. He wrote at length about his "political relationship" with Malcolm X. He collaborated with childhood friend Richard Avedon on the 1964 book Nothing Personal.[214]

Baldwin was fictionalized as the character Marion Dawes in the 1967 novel The Man Who Cried I Am by John A. Williams.[215]

Maya Angelou called Baldwin her "friend and brother" and credited him for "setting the stage" for her 1969 autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. Baldwin was made a Commandeur de la Légion d'Honneur by the French government in 1986.[216][164]

Baldwin was also a close friend of Nobel Prize-winning novelist Toni Morrison. Upon his death, Morrison wrote a eulogy for Baldwin that appeared in The New York Times. In the eulogy, entitled "Life in His Language", Morrison credits Baldwin as being her literary inspiration and the person who showed her the true potential of writing. She writes:

You knew, didn't you, how I needed your language and the mind that formed it? How I relied on your fierce courage to tame wildernesses for me? How strengthened I was by the certainty that came from knowing you would never hurt me? You knew, didn't you, how I loved your love? You knew. This then is no calamity. No. This is jubilee. "Our crown," you said, "has already been bought and paid for. All we have to do," you said, "is wear it"[217]

Although Baldwin and Truman Capote were acquaintances, they were not friends. In fact, Capote berated him several times.[218]

Legacy and critical response

[edit]Literary critic Harold Bloom characterized Baldwin as being "among the most considerable moral essayists in the United States".[219] Baldwin's influence on other writers has been profound: Toni Morrison edited the Library of America's first two volumes of Baldwin's fiction and essays: Early Novels & Stories (1998) and Collected Essays (1998). A third volume, Later Novels (2015), was edited by Darryl Pinckney, who delivered a talk on Baldwin in February 2013 to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of The New York Review of Books, during which Pinckney said, "No other black writer I'd read was as literary as Baldwin in his early essays, not even Ralph Ellison. There is something wild in the beauty of Baldwin's sentences and the cool of his tone, something improbable, too, this meeting of Henry James, the Bible, and Harlem."[220] One of Baldwin's richest short stories, "Sonny's Blues", appears in many anthologies of short fiction used in introductory college literature classes.

A street in San Francisco, Baldwin Court in the Bayview neighborhood, is named after him.[221] In 1987, Kevin Brown, a photojournalist from Baltimore, founded the National James Baldwin Literary Society. The group organizes free public events celebrating Baldwin's life and legacy. In 1992, Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts, established the James Baldwin Scholars program, an urban outreach initiative, in honor of Baldwin, who taught at Hampshire in the early 1980s. The JBS Program provides talented students of color from under-served communities an opportunity to develop and improve the skills necessary for college success through coursework and tutorial support for one transitional year, after which Baldwin scholars may apply for full matriculation to Hampshire or any other four-year college program.

Spike Lee's 1996 film Get on the Bus includes a Black gay character, played by Isaiah Washington, who punches a homophobic character, saying: "This is for James Baldwin and Langston Hughes." His name appears in the lyrics of the Le Tigre song "Hot Topic", released in 1999.[222] In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included James Baldwin on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[223]

In 2005, the United States Postal Service created a first-class postage stamp dedicated to Baldwin, which featured him on the front with a short biography on the back of the peeling paper. In 2012, Baldwin was inducted into the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display that celebrates LGBT history and people.[224] In 2014, East 128th Street between Fifth and Madison Avenues was named "James Baldwin Place" to celebrate the 90th anniversary of Baldwin's birth. He lived in the neighborhood and attended P.S. 24. Readings of Baldwin's writing were held at The National Black Theatre and a month-long art exhibition featuring works by New York Live Arts and artist Maureen Kelleher. The events were attended by Council Member Inez Dickens, who led the campaign to honor Harlem native's son; also taking part were Baldwin's family, theatre and film notables, and members of the community.[225][226]

Also in 2014, Baldwin was one of the inaugural honorees in the Rainbow Honor Walk, a walk of fame in San Francisco's Castro neighborhood celebrating LGBTQ people who have "made significant contributions in their fields."[227][228][229] In 2014, The Social Justice Hub at The New School's newly opened University Center was named the Baldwin Rivera Boggs Center after activists Baldwin, Sylvia Rivera, and Grace Lee Boggs.[230] In 2016, Raoul Peck released his documentary film I Am Not Your Negro. It is based on James Baldwin's unfinished manuscript, Remember This House. It is a 93-minute journey into Black history that connects the past of the Civil Rights Movement to the present of Black Lives Matter. It is a film that questions Black representation in Hollywood and beyond.

In 2017, Scott Timberg wrote an essay for the Los Angeles Times ("30 years after his death, James Baldwin is having a new pop culture moment") in which he noted existing cultural references to Baldwin, 30 years after his death, and concluded: "So Baldwin is not just a writer for the ages, but a scribe whose work—as squarely as George Orwell's—speaks directly to ours."[231] In June 2019, Baldwin's residence on the Upper West Side was given landmark designation by New York City's Landmarks Preservation Commission.[232][233] In June 2019, Baldwin was one of the inaugural fifty American "pioneers, trailblazers, and heroes" inducted on the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor within the Stonewall National Monument (SNM) in New York City's Stonewall Inn.[234][235] The SNM is the first U.S. national monument dedicated to LGBTQ rights and history,[236] and the wall's unveiling was timed to take place during the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots.[237] At the Paris Council of June 2019, the city of Paris voted unanimously by all political groups to name a place in the capital in honor of James Baldwin. The project was confirmed on June 19, 2019, and announced for the year 2020. In 2021, Paris City Hall announced that the writer's name would be given to the first media library in the 19th arrondissement, which is scheduled to open in 2024.[238]

On February 1, 2024, Google celebrated James Baldwin with a Google Doodle. In 2024, he appeared as a character in the television series Feud: Capote vs. The Swans, played by Chris Chalk.

On May 17, 2024, a blue plaque was unveiled by Nubian Jak Community Trust/Black History Walks to honour Baldwin at the site where in 1985 he visited the C. L. R. James Library in the London Borough of Hackney.[239][240] On August 2, 2024, The New York Public Library's Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture opened an exhibition, "JIMMY! God's Black Revolutionary Mouth" in honor of the centennial of Baldwin's birth.[241] Scheduled to run until February 28, 2025, it is accompanied by a series of public events and an exhibition of some of his manuscripts in a related exhibition "James Baldwin: Mountain to Fire" as part of the Polonsky Exhibition of The New York Public Library's Treasures.[242]

Honors and awards

[edit]- Guggenheim Fellowship, 1954.

- Eugene F. Saxton Memorial Trust Award

- Foreign Drama Critics Award

- George Polk Memorial Award, 1963

- MacDowell fellowships: 1954, 1958, 1960[243]

- Commandeur de la Légion d'honneur, 1986

Works

[edit]Novels

[edit]- 1953. Go Tell It on the Mountain

- 1956. Giovanni's Room

- 1962. Another Country

- 1968. Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone

- 1974. If Beale Street Could Talk (adapted into an Academy Award-winning 2018 film of the same name)

- 1979. Just Above My Head

- 1987. Harlem Quartet

- 1998. Early Novels & Stories: Go Tell It on the Mountain, Giovanni's Room, Another Country, Going to Meet the Man, edited by Toni Morrison.[244]

- 2015. Later Novels: Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone, If Beale Street Could Talk, Just Above My Head, edited by Darryl Pinckney.[245]

Short stories

[edit]Baldwin published six short stories in various magazines between 1948 and 1960:

- 1948. "Previous Condition". Commentary

- 1950. "The Death of the Prophet". Commentary

- 1951. "The Outing". New Story

- 1957. "Sonny's Blues". Partisan Review

- 1958. "Come Out the Wilderness". Mademoiselle

- 1960. "This Morning, This Evening, So Soon". The Atlantic Monthly

Five of these stories were collected in his 1965 collection, Going to Meet the Man, along with three other stories:

- "The Rockpile"

- "The Man Child"

- "Going to Meet the Man"

An uncollected story, "The Death of the Prophet", was eventually collected in The Cross of Redemption.

Essays

[edit]Many essays by Baldwin were published for the first time as part of collections, which also included older, individually-published works (such as above) of Baldwin's as well. These collections include:

- 1955. Notes of a Native Son[246]

- "Autobiographical Notes"

- 1949. "Everybody's Protest Novel". Partisan Review (June issue)

- 1952. "Many Thousands Gone". Partisan Review

- 1955. "Life Straight in De Eye" (later retitled "Carmen Jones: The Dark Is Light Enough"). Commentary

- 1948. "The Harlem Ghetto". Commentary

- 1948. "Journey to Atlanta". New Leader

- 1955. "Me and My House" (later retitled "Notes of a Native Son"). Harper's

- 1950. "The Negro in Paris" (later retitled "Encounter on the Seine: Black Meets Brown"). Reporter

- 1954. "A Question of Identity". PR

- 1949. "Equal in Paris". PR

- 1953. "Stranger in the Village". Harper's Magazine[247][248]

- 1961. Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son

- 1959. "The Discovery of What It Means to Be an American". The New York Times Book Review

- 1957. "Princes and Powers". Encounter

- 1960. "Fifth Avenue, Uptown: A Letter from Harlem". Esquire

- 1961. "A Negro Assays the Negro Mood". New York Times Magazine

- 1958. "The Hard Kind of Courage". Harper's Magazine

- 1959. "Nobody Knows My Name: A Letter from the South". Partisan Review

- 1956. "Faulkner and Desegregation". Partisan Review

- "In Search of a Majority" (based on a 1960 address delivered at Kalamazoo College)

- 1954. "Gide as Husband and Homosexual" (later retitled "The Male Prison"). The New Leader

- 1960. "Notes for a Hypothetical Novel" (based on a 1960 address delivered at an Esquire Magazine symposium)

- 1960. "The Precarious Vogue of Ingmar Bergman" (later retitled "The Northern Protestant"). Esquire

- "Alas, Poor Richard" (two of the three parts appeared in earlier form"

- 1961. "The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy Norman Mailer". Esquire

- 1963. The Fire Next Time

- 1962. "Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region of My Mind". The New Yorker[250]

- 1962. "My Dungeon Shook: A Letter to My Nephew". The Progressive[251]

- 1972. No Name in the Street

- 1976. The Devil Finds Work — a book-length essay published by Dial Press

- 1985. The Evidence of Things Not Seen

- 1985. The Price of the Ticket (This book is a collection of Baldwin's writings on race. Many of the items included are reprinted from Baldwin's first five books of nonfiction, but several are collected here for the first time:

- "The Price of the Ticket"

- 1948. "Lockridge: The American Myth". New Leader

- 1956. "The Crusade of Indignation". The Nation

- 1959. "On Catfish Row: Porgy and Bess in the Movies". Commentary

- 1960. "They Can't Turn Back". Mademoiselle

- 1961. "The Dangerous Road before Martin Luther King". Harper's

- 1961. "The New Lost Generation". Esquire

- 1962. "The Creative Process". Creative America

- 1962. "Color". |Esquire

- 1963. "A Talk to Teachers"[252]

- 1964. "Nothing Personal" (originally text for a book of photographs by Richard Avedon)

- 1964. "Words of a Native Son". Playboy

- 1965. "The American Dream and the American Negro" (based on remarks by Baldwin made in his debate with William F. Buckley)

- 1965. "The White Man's Guilt". Ebony

- 1966. "A Report from Occupied Territory". The Nation

- 1967. "Negroes Are Anti-Semitic Because They're Anti-White". New York Times Magazine[253]

- 1968. "White Racism or World Community?" Ecumenical Review

- 1969. "Sweet Lorraine". Esquire

- 1976. "How One Black Man Came To Be an American: A Review of Roots". The New York Times Book Review

- 1977. "An Open Letter to Mr. Carter". The New York Times

- 1977. "Every Good-Bye Ain't Gone". New York.

- 1979. "If Black English Isn't a Language, Then Tell Me, What Is?" The New York Times

- 1979. "An Open Letter to the Born Again". The Nation

- 1980. "Dark Days". Esquire

- 1980. "Notes on the House of Bondage". The Nation

- 1985. "Here Be Dragons" (also titled "Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhood"). Playboy

- 1998. Collected Essays: Notes of a Native Son, Nobody Knows My Name, The Fire Next Time, No Name in the Street, The Devil Finds Work, Other Essays, edited by Toni Morrison.[254]

- 1947. "Smaller than Life". The Nation

- 1947. "History as Nightmare". New Leader

- 1948. "The Image of the Negro". Commentary

- 1949. "Preservation of Innocence". Zero

- 1951. "The Negro at Home and Abroad". Reporter

- 1959. "Sermons and Blues". The New York Times Book Review

- 1964. "This Nettle, Danger...". Show

- 1965. "On the Painter Beauford Delaney". Transition

- 1977. "Last of the Great masters". The New York Times Book Review

- 1984. "Introduction to Notes of a Native Son"

- 2010. The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings[255]

- 1959. "Mass Culture and the Creative Artist: Some Personal Notes". Culture for the Millions. 1961

- 1959. "A Word from Writer Directly to Reader". Fiction of the Fifties

- 1961. From Nationalism, Colonialism, and The United States: One Minte to Twelve – A Forum

- 1966. "Theatre: The Negro In and Out". Negro Digest

- 1961. "Is A Raisin in the Sun a Lemon in the Dark?" Tone

- 1962. "As Much Truth as One Can Bear". The New York Times Book Review

- 1962. "Geraldine Page: Bird of Light". Show

- 1962. "From What's the Reason Why?: A Symposium by Best-Selling Authors". The New York Times Book Review

- 1963. "The Artist's Struggle for Integrity". Liberation