Spanish dialects and varieties

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (April 2021) |

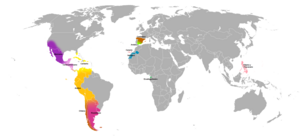

In other colors, the extent of the other languages of Spain in the bilingual areas.

Some of the regional varieties of the Spanish language are quite divergent from one another, especially in pronunciation and vocabulary, and less so in grammar.

While all Spanish dialects adhere to approximately the same written standard, all spoken varieties differ from the written variety, to different degrees. There are differences between European Spanish (also called Peninsular Spanish) and the Spanish of the Americas, as well as many different dialect areas both within Spain and within the Americas. Chilean and Honduran Spanish have been identified by various linguists as the most divergent varieties.[1]

Prominent differences in pronunciation among dialects of Spanish include:

- the maintenance or lack of distinction between the phonemes /θ/ and /s/ (distinción vs. seseo and ceceo);

- the maintenance or loss of distinction between phonemes represented orthographically by ll and y (yeísmo);

- the maintenance of syllable-final [s] vs. its weakening to [h] (called aspiration, or more precisely debuccalization), or its loss; and

- the tendency, in areas of central Mexico and of the Andean highlands, to reduction (especially devoicing), or loss, of unstressed vowels, mainly when they are in contact with voiceless consonants.[2][3][4]

Among grammatical features, the most prominent variation among dialects is in the use of the second-person pronouns. In Hispanic America the only second-person plural pronoun, for both formal and informal treatment, is ustedes, while in most of Spain the informal second-person plural pronoun is vosotros with ustedes used only in the formal treatment. For the second-person singular familiar pronoun, some American dialects use tú (and its associated verb forms), while others use either vos (see voseo) or both tú and vos [citation needed] (which, together with usted, can make for a possible three-tiered distinction of formalities).

There are significant differences in vocabulary among regional varieties of Spanish, particularly in the domains of food products, everyday objects, and clothes; and many American varieties show considerable lexical influence from Native American languages.

Sets of variants

[edit]While there is no broad consensus on how Latin American Spanish dialects should be classified, the following scheme which takes into account phonological, grammatical, socio-historical, and language contact data provides a reasonable approximation of Latin American dialect variation:[5][6]

- Mexican (except coastal areas) and southwestern US (including New Mexican).

- Central American, including southwestern Mexico.

- Caribbean (Cuba, Venezuela, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Panama, Caribbean Colombia, Trinidad and Caribbean and Pacific Coasts of Mexico).

- Inland Colombia and the speech of neighboring areas of Venezuela.

- Pacific coast of Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru

- Andean regions of Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, southwestern Colombia, northwestern Argentina, and northeastern Chile.

- Chilean, including western Argentina.

- Paraguayan, including northeastern Argentina, and eastern Bolivia.

- Rioplatense (central-west Argentina and Uruguay).

While there are other types of regional variation in Peninsular Spanish, and the Spanish of bilingual regions shows influence from other languages, the greatest division in Old World varieties is from north to south, with a central-northern dialect north of Madrid, an Andalusian dialect to the south, and an intermediary region between the two most important dialect zones. Meanwhile, the Canary Islands constitute their own dialect cluster, whose speech is most closely related to that of western Andalusia.[7][8][9]

The non-native Spanish in Equatorial Guinea and Western Sahara (formerly Spanish Sahara) has been influenced mainly by varieties from Spain. Spanish is also an official language in Equatorial Guinea, and many people speak it fluently.[10]

Though no longer an official language in the Philippines, Philippine Spanish has had a tremendous influence on the native tongues of the archipelago, including Filipino.

The Spanish spoken in Gibraltar is essentially not different from the neighboring areas in Spain, except for code-switching with English and some unique vocabulary items. It is frequently blended with English as a sort of Spanglish known as Llanito.

Judaeo-Spanish, a "Jewish language", encompasses a number of linguistic varieties based mostly on 15th-century Spanish; it is still spoken in a few small communities, mainly in Israel, but also in Turkey and a number of other countries.[11] As Jews have migrated since their expulsion from Iberia, the language has picked up several loan words from other languages and developed unique forms of spelling, grammar, and syntax. It can be considered either a very divergent dialect of Spanish, retaining features from Old Spanish,[12] or a separate language.

Pronunciation

[edit]Distinción vs. seseo and ceceo

[edit]

The distinction between /s/ and /θ/ is maintained in northern Spain (in all positions) and in south-central Spain (only in syllable onset),[citation needed] while the two phonemes are not distinguished in the Americas, the Canary Islands, the Philippines and much of Andalusia. The maintenance of phonemic contrast is called distinción in Spanish. In areas that do not distinguish them, they are typically realized as [s], though in parts of southern Andalusia the realization is closer to [θ]; in Spain uniform use of [θ] is called ceceo and uniform use of [s] seseo.

In dialects with seseo the words casa ('house') and caza ('hunt') are pronounced as homophones (generally [ˈkasa]), whereas in dialects with distinción they are pronounced differently (as [ˈkasa] and [ˈkaθa] respectively). The symbol [s] stands for a voiceless sibilant like the s of English sick, while [θ] represents a voiceless interdental fricative like the th of English think.

In some cases where the phonemic merger would render words homophonic in the Americas, one member of the pair is frequently replaced by a synonym or derived form—e.g. caza replaced by cacería, or cocer ('to boil'), homophonic with coser ('to sew'), replaced by cocinar. For more on seseo, see González-Bueno.[13]

Yeísmo

[edit]

Traditionally Spanish had a phonemic distinction between /ʎ/ (a palatal lateral approximant, written ll) and /ʝ/ (a palatal approximant, written y). But for most speakers in Spain and the Americas, these two phonemes have been merged in the phoneme /ʝ/. This merger results in the words calló ('silenced') and cayó ('fell') being pronounced the same, whereas they remain distinct in dialects that have not undergone the merger. The use of the merged phoneme is called "yeísmo".

In Spain, the distinction is preserved in some rural areas and smaller cities of the north, while in South America the contrast is characteristic of bilingual areas where Quechua languages and other indigenous languages that have the /ʎ/ sound in their inventories are spoken (this is the case of inland Peru and Bolivia), and in Paraguay.[14][15]

The phoneme /ʝ/ can be pronounced in a variety of ways, depending on the dialect. In most of the area where yeísmo is present, the merged phoneme /ʝ/ is pronounced as the approximant [ʝ], and also, in word-initial positions, an affricate [ɟʝ]. In the area around the Río de la Plata (Argentina, Uruguay), this phoneme is pronounced as a palatoalveolar sibilant fricative, either as voiced [ʒ] or, especially by young speakers, as voiceless [ʃ].

Variants of /s/

[edit]One of the most distinctive features of the Spanish variants is the pronunciation of /s/ when it is not aspirated to [h] or elided. In northern and central Spain, and in the Paisa Region of Colombia, as well as in some other, isolated dialects (e.g. some inland areas of Peru and Bolivia), the sibilant realization of /s/ is an apico-alveolar retracted fricative [s̺], a sound transitional between laminodental [s] and palatal [ʃ]. However, in most of Andalusia, in a few other areas in southern Spain, and in most of Latin America it is instead pronounced as a lamino-alveolar or dental sibilant. The phoneme /s/ is realized as [z] or [z̺] before voiced consonants when it is not aspirated to [h] or elided; [z̺] is a sound transitional between [z] and [ʒ]. Before voiced consonants, [z ~ z̺] is more common in natural and colloquial speech and oratorical pronunciation, [s ~ s̺] is mostly pronounced in emphatic and slower speech.

In the rest of the article, the distinction is ignored and the symbols ⟨s z⟩ are used for all alveolar fricatives.

Debuccalization of coda /s/

[edit]

In much of Latin America—especially in the Caribbean and in coastal and lowland areas of Central and South America—and in the southern half of Spain, syllable-final /s/ is either pronounced as a voiceless glottal fricative, [h] (debuccalization, also frequently called "aspiration"), or not pronounced at all. In some varieties of Latin American Spanish (notably Honduran and Salvadoran Spanish) this may also occur intervocalically within an individual word—as with nosotros, which may be pronounced as [noˈhotɾoh]—or even in initial position. In southeastern Spain (eastern Andalusia, Murcia and part of La Mancha), the distinction between syllables with a now-silent s and those originally without s is preserved by pronouncing the syllables ending in s with [æ, ɛ, ɔ] (that is, the open/closed syllable contrast has been turned into a tense/lax vowel contrast); this typically affects the vowels /a/, /e/ and /o/, but in some areas even /i/ and /u/ are affected, turning into [ɪ, ʊ]. For instance, todos los cisnes son blancos ('all the swans are white'), can be pronounced [ˈtoðoh loh ˈθihne(s) som ˈblaŋkoh], or even [ˈtɔðɔ lɔ ˈθɪɣnɛ som ˈblæŋkɔ] (Standard Peninsular Spanish: [ˈtoðoz los ˈθizne(s) som ˈblaŋkos], Latin American Spanish: [ˈtoðoz lo(s) ˈsizne(s) som ˈblaŋkos]). This vowel contrast is sometimes reinforced by vowel harmony, so that casas [ˈkæsæ] 'houses' differs from casa [ˈkasa] not only by the lack of the final [s] in the former word but also in the quality of both of the vowels. For those areas of southeastern Spain where the deletion of final /s/ is complete, and where the distinction between singular and plural of nouns depends entirely on vowel quality, it has been argued that a set of phonemic splits has occurred, resulting in a system with eight vowel phonemes in place of the standard five.[16][17]

In the dialects that feature s-aspiration, it works as a sociolinguistic variable, [h] being more common in natural and colloquial speech, whereas [s] tends to be pronounced in emphatic and slower speech. In oratorical pronunciation, it depends on the country and speaker; if the Spanish speaker chooses to pronounces all or most of syllable-final [s], it is mostly voiced to [z] before voiced consonants.

Vowel reduction

[edit]Although the vowels of Spanish are relatively stable from one dialect to another, the phenomenon of vowel reduction—devoicing or even loss—of unstressed vowels in contact with voiceless consonants, especially /s/, can be observed in the speech of central Mexico (including Mexico City).[citation needed] For example, it can be the case that the words pesos ('pesos [money]'), pesas ('weights'), and peces ('fish [pl.]') sound nearly the same, as [ˈpesː]. One may hear pues ('well (then)') pronounced [ps̩]. Some efforts to explain this vowel reduction link it to the strong influence of Nahuatl and other Native American languages in Mexican Spanish.[citation needed]

Pronunciation of j

[edit]In the 16th century, as the Spanish colonization of the Americas was beginning, the phoneme now represented by the letter j had begun to change its place of articulation from palato-alveolar [ʃ] to palatal [ç] and to velar [x], like German ch in Bach (see History of Spanish and Old Spanish language). In southern Spanish dialects and in those Hispanic American dialects strongly influenced by southern settlers (e.g. Caribbean Spanish), rather than the velar fricative [x], the sound was backed all the way to [h], like English h in hope. Glottal [h] is nowadays the standard pronunciation for j in Caribbean dialects (Cuban, Dominican, and Puerto Rican) as well as in mainland Venezuela, in most Colombian dialects excepting Pastuso dialect that belongs to a continuum with Ecuadorian Spanish, much of Central America, southern Mexico,[18] the Canary Islands, Extremadura and western Andalusia in Spain; in the rest of Spain, [x] alternates with a uvular fricative allophone [χ]. In the rest of the Americas, the velar fricative [x] is prevalent. In Chile, /x/ is fronted to [ç] (like German ch in ich) when it precedes the front vowels /i/ and /e/: gente [ˈçente], jinete [çiˈnete]; in other phonological environments it is pronounced [x] or [h].

For the sake of simplicity, these are given a broad transcription ⟨x⟩ in the rest of the article.

Word-final -n

[edit]In standard European Spanish, as well as in many dialects in the Americas (e.g. standard Argentine or Rioplatense, inland Colombian, and Mexican), word-final /n/ is, by default (i.e. when followed by a pause or by an initial vowel in the following word), alveolar, like English [n] in pen. When followed by a consonant, it assimilates to that consonant's place of articulation, becoming dental, interdental, palatal, or velar. In some dialects, however, word-final /n/ without a following consonant is pronounced as a velar nasal [ŋ] (like the -ng of English long), and may produce vowel nasalization. In these dialects, words such as pan ('bread') and bien ('well') may sound like pang and byeng to English-speakers. Velar -n is common in many parts of Spain (Galicia, León, Asturias, Murcia, Extremadura, Andalusia, and Canary Islands). In the Americas, velar -n is prevalent in all Caribbean dialects, Central American dialects, the coastal areas of Colombia, Venezuela, much of Ecuador, Peru, and northern Chile.[18] This velar -n likely originated in the northwest of Spain, and from there spread to Andalusia and then the Americas.[19] Loss of final -n with strong nasalization of the preceding vowel is not infrequent in all those dialects where velar -n exists. In much of Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela (except for the Andean region) and Dominican Spanish, any pre-consonantal nasal can be realized [ŋ]; thus, a word like ambientación can be pronounced [aŋbjeŋtaˈsjoŋ].

R sounds

[edit]All varieties of Spanish distinguish between a "single-R" and a "double-R" phoneme. The single-R phoneme corresponds to the letter r written once (except when word-initial or following l, n, or s) and is pronounced as [ɾ], an alveolar flap—like American English tt in better—in virtually all dialects. The single-R/double-R contrast is neutralized in syllable-final position, and in some dialects these phonemes also lose their contrast with /l/, so a word such as artesanía may sound like altesanía. This neutralization or "leveling" of coda /r/ and /l/ is frequent in dialects of southern Spain, the Caribbean, Venezuela and coastal Colombia.[18]

The double-R phoneme is spelled rr between vowels (as in carro 'car') and r word-initially (e.g. rey 'king', ropa 'clothes') or following l, n, or s (e.g. alrededor 'around', enriquecer 'enrich', enrollar 'roll up', enrolar 'enroll', honra 'honor', Conrado 'Conrad', Israel 'Israel'). In most varieties it is pronounced as an alveolar trill [r], and that is considered the prestige pronunciation. Two notable variants occur additionally: one sibilant and the other velar or uvular. The trill is also found in lexical derivations (morpheme-initial positions), and prefixation with sub and ab: abrogado [aβroˈɣa(ð)o], 'abrogated', subrayar [suβraˈʝar], 'to underline'. The same goes for the compound word ciudadrealeño (from Ciudad Real). However, after vowels, the initial r of the root becomes rr in prefixed or compound words: prorrogar, infrarrojo, autorretrato, arriesgar, puertorriqueño, Monterrey. In syllable-final position, inside a word, the tap is more frequent, but the trill can also occur (especially in emphatic[20] or oratorical[21] style) with no semantic difference, especially before l, m, n, s, t, or d—thus arma ('weapon') may be either [ˈaɾma] (tap) or [ˈarma] (trill), perla ('pearl') may be either [ˈpeɾla] or [ˈperla], invierno ('winter') may be [imˈbjeɾno] or [imˈbjerno], verso ('verse') may be [ˈbeɾso] or [ˈberso], and verde ('green') [ˈbeɾðe] or [ˈberðe]. In word-final position the rhotic will usually be: either a trill or a tap when followed by a consonant or a pause, as in amo[r ~ ɾ] paterno 'paternal love') and amo[r ~ ɾ], with the tap being more frequent and the trill before l, m, n, s, t, d, or sometimes a pause; or a tap when followed by a vowel-initial word, as in amo[ɾ] eterno 'eternal love') (Can be a trill or tap with a temporary glottal stop in emphatic speech: amo[rʔ ~ ɾʔ] eterno, with trill being more common). Morphologically, a word-final rhotic always corresponds to the tapped [ɾ] in related words. Thus, the word olor 'smell' is related to olores, oloroso 'smells, smelly' and not to *olorres, *olorroso, and the word taller 'workshop' is related to talleres 'workshops' and not to *tallerres.[22] When two rhotics occur consecutively across a word or prefix boundary, they result in one trill, so that da rosas ('s/he gives roses') and dar rosas ('give roses') are either neutralized, or distinguished by a longer trill in the latter phrase, which may be transcribed as [rr] or [rː] (although this is transcribed with ⟨ɾr⟩ in Help:IPA/Spanish, even though it differs from [r] purely by length); da rosas and dar rosas may be distinguished as [da ˈrosas] vs. [darˈrosas], or they may fall together as the former.[23][24]

The pronunciation of the double-R phoneme as a voiced strident (or sibilant) apical fricative is common in New Mexico, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, and Paraguay; in western and northern Argentina; and among older speakers in highland areas of Colombia.[25] Some linguists have attempted to explain the assibilated rr (written in IPA as [r̝]) as a result of influence from Native American languages, and it is true that in the Andean regions mentioned an important part of the population is bilingual in Spanish and one or another indigenous language. Nonetheless, other researchers have pointed out that sibilant rr in the Americas may not be an autonomous innovation, but rather a pronunciation that originated in some northern Spanish dialects and then was exported to the Americas. Spanish dialects spoken in the Basque Country, Navarre, La Rioja, and northern Aragon[26] (regions that contributed substantially to Spanish-American colonization) show the fricative or postalveolar variant for rr (especially for the word-initial rr sound, as in Roma or rey). This is also pronounced voiceless when the consonants after the trill are voiceless and speaking in emphatic speech; it is written as [r̝̊], it sounds like a simultaneous [r] and [ʃ]. In Andean regions, the alveolar trill is realized as an alveolar approximant [ɹ] or even as a voiced apico-alveolar [ɹ̝], and it is quite common in inland Ecuador, Peru, most of Bolivia and in parts of northern Argentina and Paraguay. The alveolar approximant realization is particularly associated with the substrate of Native American languages, as is the assibilation of /ɾ/ to [ɾ̞] in Ecuador and Bolivia. Assibilated trill is also found in dialects in the /sr/ sequence wherein /s/ is unaspirated, example: las rosas [la ˈr̝osas] ('the roses'), Israel [iˈr̝ael]. The assibilated trill in this example is sometimes pronounced voiceless in emphatic and slower speech: las rosas [la ˈr̝̊osas] ('the roses'), Israel [iˈr̝̊ael]. The other major variant for the rr phoneme—common in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic—is articulated at the back of the mouth, either as a glottal [h] followed by a voiceless apical trill [r̥] or, especially in Puerto Rico, with a posterior articulation that ranges variously from a velar fricative [x] to a uvular trill [ʀ].[27] Canfield describes it as a voiceless uvular trill [ʀ̥].[28] These realizations for rr maintain their contrast with the phoneme /x/, as the latter tends to be realized as a soft glottal [h]: compare Ramón [xaˈmoŋ] ~ [ʀ̥aˈmoŋ] ('Raymond') with jamón [haˈmoŋ] ('ham').

In Puerto Rico, syllable-final /r/ can be realized as [ɹ] (probably an influence of American English), aside from [ɾ], [r], and [l], so that verso ('verse') becomes [ˈbeɹso], alongside [ˈbeɾso], [ˈberso], or [ˈbelso]; invierno ('winter') becomes [imˈbjeɹno], alongside [imˈbjeɾno], [imˈbjerno], or [imˈbjelno]; and parlamento (parliament) becomes [paɹlaˈmento], alongside [paɾlaˈmento], [parlaˈmento], or [palaˈmento]. In word-final position, the realization of /r/ depends on whether it is followed by a consonant-initial word or a pause, on the one hand, or by a vowel-initial word, on the other:

- Before a consonant or pause: a trill, a tap, an approximant, the lateral [l], or elided, as in amo[r ~ ɾ ~ ɹ ~ l ~ ∅] paterno ('paternal love').

- Before a vowel: a tap, an approximant, or the lateral [l], as in amo[ɾ ~ ɹ ~ l] eterno ('eternal love').

The same situation happens in Belize and the Archipelago of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina, in these cases an influence of British English.

Although in most Spanish-speaking territories and regions, guttural or uvular realizations of /r/ are considered a speech defect, back variants for /r/ ([ʀ], [x] or [χ]) are widespread in rural Puerto Rican Spanish and in the dialect of Ponce,[29] whereas they are heavily stigmatized in the dialect of the capital San Juan.[30] To a lesser extent, velar variants of /r/ are found in some rural Cuban (Yateras, Guantánamo Province)[31] and Dominican vernaculars (Cibao, eastern rural regions of the country).[32]

In Paraguay, syllable-final /r/ is pronounced as [ɹ] before l or s and word-final position, influenced by a substrate from Native American languages.

In Chile, as in Andalusia, the archiphoneme /r/ in the sequence /rn/ is sometimes assimilated to [nn] in lower-class speakers, and sometimes in educated speakers. Thus, jornada /xorˈnada/ 'workday' may be pronounced [xonˈnaː].

Additionally, in the Basque-speaking areas of Spain, the uvular articulation for /r/, [ʁ], has a higher prevalence among bilinguals than among Spanish monolinguals.[33]

Pronunciation of x

[edit]The letter x usually represents the phoneme sequence /ɡs/. An exception to this is the pronunciation of the x in some place names, especially in Mexico, such as Oaxaca and the name México itself, reflecting an older spelling (see "Name of Mexico"). Some personal names, such as Javier, Jiménez, Rojas, etc., also are occasionally spelled with X: Xavier, Ximénez, Roxas, etc., where the letter is pronounced /x/. A small number of words in Mexican Spanish retain the historical /ʃ/ pronunciation, e.g. mexica.

There are two possible pronunciations of /ɡs/ in standard speech: the first one is [ks], with a voiceless plosive, but it is commonly realized as [ɣs] instead (hence the phonemic transcription /ɡs/). Voicing is not contrastive in the syllable coda.[34]

In dialects with seseo, c following x pronounced /ɡs/ is deleted, yielding pronunciations such as [eɣseˈlente, ek-] for excelente.

Adoption of the affricates tz and tl

[edit]Mexican Spanish and some other Latin American dialects have adopted from the native languages the voiceless alveolar affricate [ts] and many words with the cluster [tl] (originally an affricate [tɬ]) represented by the respective digraphs ⟨tz⟩ and ⟨tl⟩, as in the names Azcapotzalco and Tlaxcala. /tl/ is a valid onset cluster in Latin America, with the exception of Puerto Rico, in the Canary Islands, and in the northwest of Spain, including Bilbao and Galicia. In these dialects, words of Greek and Latin origin with ⟨tl⟩, such as Atlántico and atleta, are also pronounced with onset /tl/: [aˈtlantiko], [aˈtleta]. In other dialects, the corresponding phonemic sequence is /dl/ (where /l/ is the onset), with the coda /d/ realized variously as [t] and [ð]. The usual pronunciation of those words in most of Spain is [aðˈlantiko] and [aðˈleta].[35][36][37]

The [ts] sound also occurs in European Spanish in loanwords of Basque origin (but only learned loanwords, not those inherited from Roman times), as in abertzale. In colloquial Castilian it may be replaced by /tʃ/ or /θ/. In Bolivian, Paraguayan, and Coastal Peruvian Spanish, [ts] also occurs in loanwords of Japanese origin.[citation needed]

Other loaned phonetics

[edit]Spanish has a fricative [ʃ] for loanwords of origins from native languages in Mexican Spanish, loanwords of French, German and English origin in Chilean Spanish, loanwords of Italian, Galician, French, German and English origin in Rioplatense Spanish and Venezuelan Spanish, Chinese loanwords in Coastal Peruvian Spanish, Japanese loanwords in Bolivian Spanish, Paraguayan Spanish, Coastal Peruvian Spanish, Basque loanwords in Castilian Spanish (but only learned loanwords, not those inherited from Roman times), and English loanwords in Puerto Rican Spanish and all dialects.[38] [citation needed]

Pronunciation of ch

[edit]The Spanish digraph ch (the phoneme /tʃ/) is pronounced [tʃ] in most dialects. However, it is pronounced as a fricative [ʃ] in some Andalusian dialects, New Mexican Spanish, some varieties of northern Mexican Spanish, informal and sometimes formal Panamanian Spanish, and informal Chilean Spanish. In Chilean Spanish this pronunciation is viewed as undesirable, while in Panama it occurs among educated speakers. In Madrid and among upper- and middle-class Chilean speakers, it can be pronounced as the alveolar affricate [ts].

Open-mid and open front vowels

[edit]In some dialects of southeastern Spain (Murcia, eastern Andalusia and a few adjoining areas) where the weakening of final /s/ leads to its disappearance, the "silent" /s/ continues to have an effect on the preceding vowel, opening the mid vowels /e/ and /o/ to [ɛ] and [ɔ] respectively, and fronting the open central vowel /a/ toward [æ]. Thus the singular/plural distinction in nouns and adjectives is maintained by means of the vowel quality:

- libro [ˈliβɾo] 'book', but libros [ˈliβɾɔ] 'books'.

- libre [ˈliβɾe] 'free, singular ', but libres [ˈliβɾɛ] 'free, plural'.

- libra [ˈliβɾa] 'pound', but libras [ˈliβɾæ] 'pounds'.[39]

Furthermore, this opening of final mid vowels can affect other vowels earlier in the word, as an instance of metaphony:

- lobo [ˈloβo] 'wolf', but lobos [ˈlɔβɔ] 'wolves'.[39]

(In the remaining dialects, the mid vowels have nondistinctive open and closed allophones determined by the shape of the syllable or by contact with neighboring phonemes. See Spanish phonology.)

Post-tonic e and o

[edit]Final, non-stressed /e/ and /o/ may be raised to [i] and [u] respectively in some rural areas of Spain and Latin America. Examples include noche > nochi 'night', viejo > vieju. In Spain, this is mainly found in Galicia and other northern areas. This type of raising carries negative prestige.[40]

Judaeo-Spanish

[edit]Judaeo-Spanish (often called Ladino) refers to the Romance dialects spoken by Jews whose ancestors were expelled from Spain near the end of the 15th century.

These dialects have important phonological differences compared to varieties of Spanish proper; for example, they have preserved the voiced/voiceless distinction among sibilants as they were in Old Spanish. For this reason, the letter ⟨s⟩, when written single between vowels, corresponds to a voiced [z]—e.g. rosa [ˈroza] ('rose'). Where ⟨s⟩ is not between vowels and is not followed by a voiced consonant, or when it is written double, it corresponds to voiceless [s]—thus assentarse [asenˈtarse] ('to sit down'). And due to a phonemic neutralization similar to the seseo of other dialects, the Old Spanish voiced ⟨z⟩ [dz] and the voiceless ⟨ç⟩ [ts] have merged, respectively, with /z/ and /s/—while maintaining the voicing contrast between them. Thus fazer ('to make') has gone from the medieval [faˈdzer] to [faˈzer], and plaça ('town square') has gone from [ˈplatsa] to [ˈplasa].[41]

A related dialect is Haketia, the Judaeo-Spanish of northern Morocco. This too tended to assimilate with modern Spanish, during the Spanish occupation of the region. Tetuani Ladino was brought to Oran in Algeria.

Intonation

[edit]Patterns of intonation differ significantly according to dialect, and native speakers of Spanish use intonation to quickly identify different accents. To give some examples, intonation patterns differ between Peninsular and Mexican Spanish, and also between northern Mexican Spanish and accents of the center and south of the country. Argentine Spanish is also characterized by its unique intonation patterns which are supposed to be influenced by the languages of Italy, particularly Neapolitan. Language contact can affect intonation as well, as the Spanish spoken in Cuzco and Mallorca show influence from Quechua and Catalan intonation patterns, respectively, and distinct intonation patterns are found in some ethnically homogenous Afro-Latino communities. Additionally, some scholars have historically argued that indigenous languages influenced the development of Latin America's regional intonation patterns.[42][43][44]

Grammar

[edit]Second-person pronouns and verbs

[edit]Spanish is a language with a "T–V distinction" in the second person, meaning that there are different pronouns corresponding to "you" which express different degrees of formality. In most varieties, there are two degrees, namely "formal" and "familiar" (the latter is also called "informal").

For the second person formal, virtually all Spanish dialects of Spain and the Americas use usted and ustedes (singular and plural respectively). But for the second person familiar, there is regional variation—between tú and vos for the singular, and, separately, between vosotros and ustedes for the plural. The use of vos (and its corresponding verb forms) rather than tú is called voseo.[45]

Each of the second-person pronouns has its historically corresponding verb forms, used by most speakers. Most voseo speakers use both the pronoun vos and its historically corresponding verb forms (e.g. vos tenés, 'you have'). But some dialects use the pronoun tú with "vos verb forms" (verbal voseo—tú tenés), while others use vos with "tú verb forms" (pronominal voseo—vos tienes).

Second-person singular

[edit]

In most dialects the familiar second person singular pronoun is tú (from Latin tū), and the formal pronoun is usted (usually considered to originate from vuestra merced, meaning 'your grace' or, literally, 'your mercy'). In a number of regions in the Americas, tú is replaced by another pronoun, vos, and the verb conjugation changes accordingly (see details below). Spanish vos comes from Latin vōs, the second person plural pronoun in Latin.

In any case, there is wide variation as to when each pronoun (formal or familiar) is used. In Spain, tú is familiar (for example, used with friends), and usted is formal (for example, used with older people). In recent times, there has been a noticeable tendency to extend the use of tú even in situations previously reserved for usted. Meanwhile, in several countries (in parts of Middle America, especially, Costa Rica and Colombia), the formal usted is also used to denote a closer personal relationship. Many Colombians and some Chileans, for instance, use usted for a child to address a parent and also for a parent to address a child. Some countries, such as Cuba and the Dominican Republic, prefer the use of tú even in very formal circumstances, and usted is seldom used.

Meanwhile, in other countries, the use of formal rather than familiar second-person pronouns denotes authority. In Peru, for example, senior military officers use tú to speak to their subordinates, but junior officers use only usted to address their superior officers.

Using the familiar tú, especially in contexts where usted was to be expected, is called tuteo. The corresponding verb is tutear (a transitive verb, the direct object being the person addressed with the pronoun). The verb tutear is used even in those dialects whose familiar pronoun is vos and means 'to treat with the familiar second-person pronoun'.[46]

Pronominal voseo, the use of the pronoun vos instead of tú, is the prevalent form of the familiar second person singular pronoun in Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Paraguay, Argentina and Uruguay. In those countries, it is used by many to address others in all kinds of contexts, often regardless of social status or age, including by cultured/educated speakers and writers, in television, advertisements, and even in translations from other languages. In Guatemala and Uruguay, vos and tú are used concurrently, but vos is much more common. Both pronouns use the verb forms normally associated with vos (vos querés / tú querés, 'you want').

The name Rioplatense is applied to the dialect of Spanish spoken around the mouth of the Río de la Plata and the lower course of the Paraná River, where vos, not tú, is invariably used, with the vos verb forms (vos tenés). The area comprises the most populous part of Argentina (the provinces of Buenos Aires and Santa Fe) as well as an important part of Uruguay, including Montevideo, the capital.

In Ecuador, vos is the most prominent form throughout the Sierra region of the country, though it does coexist with usted and the lesser-used tú. In this region, vos is regarded as the conversational norm, but it is not used in public discourse or the mass media. The choice of pronoun to be used depends on the participants' likeness in age and/or social status. Based on these factors, speakers can assess themselves as being equal, superior, or inferior to the addressee, and the choice of pronoun is made on this basis, sometimes resulting in a three-tiered system. Ecuadorians of the Highlands thus generally use vos among familiarized equals or by superiors (in both social status and age) to inferiors; tú among unfamiliarized equals, or by a superior in age but inferior in social status; and usted by both familiarized and unfamiliarized inferiors, or by a superior in social status but inferior in age. In the more populated coastal region, the form tú is used in most situations, usted being used only for unfamiliar and/or superior addressees.

Vos can be heard throughout most of Chile, Bolivia, and a small part of Peru as well, but in these places it is regarded as substandard. It is also used as the conversational norm in the Paisa Region and the southwest region of Colombia, in Zulia State (Venezuela), in Honduras, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and the state of Chiapas in Mexico.

In Chile, even though tú is the prestige pronoun among educated speakers, the use of "verbal voseo", i.e. "tú + verb conjugation of vos" (e.g. tú podís) is widespread. On the other hand, "pronominal voseo", the use of the pronoun vos—pronounced with aspiration of the final /s/—is used derisively in informal speech between close friends as playful banter (usually among men) or, depending on the tone of voice, as an offensive comment.

In Colombia, the choice of second person singular varies with location. In most of inland Colombia (especially the Andean region), usted is the pronoun of choice for all situations, even in speaking between friends or family; but in large cities (especially Bogotá), the use of tú is becoming more accepted in informal situations, especially between young interlocutors of opposite sexes and among young women. In Valle del Cauca (Cali), Antioquia (Medellín) and the Pacific coast, the pronouns used are vos and usted. On the Caribbean coast (mainly Barranquilla and Cartagena), tú is used for practically all informal situations and many formal situations as well, usted being reserved for the most formal environments. A peculiarity occurs in the Altiplano Cundiboyacense and among some speakers in Bogotá: usted is replaced by sumercé for formal situations (it is relatively easy to identify a Boyacense by his/her use of this pronoun). Sumercé comes from su merced ('your mercy').

In parts of Spain, a child used to use not tú but usted to address a parent. Today, however, this usage is unusual. Among the factors for the ongoing replacement of usted by tú are the new social relevance of youth and the reduction of social differences. In particular, it has been attributed[by whom?] to the egalitarianism of the right-wing Falange party. By contrast, Spanish leftists of the early 20th century would address their comrades as usted as a show of respect and workers' dignity.

According to Joan Coromines, by the 16th century, the use of vos (as a second person singular pronoun) had been reduced to rural areas of Spain, which were a source of many emigrants to the New World, and so vos became the unmarked form in many areas of Latin America.[47][48]

A slightly different explanation is that in Spain, even if vos (as a singular) originally denoted the high social status of those who were addressed as such (monarchs, nobility, etc.), the people never used the pronoun themselves since there were few or no people above them in society. Those who used vos were people of the lower classes and peasants. When the waves of Spanish immigrants arrived to populate the New World, they primarily came from these lower classes. In the New World, wanting to raise their social status from what it was in Spain, they demanded to be addressed as vos.[citation needed]

Through the widespread use of vos in the Americas, the pronoun was transformed into an indicator of low status not only for the addresser but also for the addressee. Conversely, in Spain, vos is now considered a highly exalted archaism virtually confined to liturgy.

Speakers of Ladino still use vos as it was used in the Middle Ages, to address people higher on the social ladder. The pronoun usted had not been introduced to this dialect of Spanish when the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492 so vos is still used in Ladino much as usted is used in modern Spanish.

A variant of usted, vusted, can be heard in Andean regions of South America. Other, less frequent forms analogous to usted are vuecencia (short for vuestra excelencia), and usía (from vuestra señoría).

There is a traditional assumption that Chilean and River Plate voseo verb forms are derived from those corresponding to vosotros. This assumption, however, has been challenged, in an article by Baquero & Westphal (2014)—in the theoretical framework of classical generative phonology—as synchronically inadequate, on the grounds that it requires at least six different rules, including three monophthongization processes that lack phonological motivation. Alternatively, the article argues that the Chilean and River Plate voseo verb forms are synchronically derived from underlying representations that coincide with those corresponding to the non-honorific second person singular tú. The proposed theory requires the use of only one special rule in the case of Chilean voseo. This rule—along with other rules that are independently justified in the language—makes it possible to derive synchronically all Chilean and River Plate voseo verb forms in a straightforward manner. The article additionally solves the problem posed by the alternate verb forms of Chilean voseo such as the future indicative (e.g. vay a bailar 'will you dance?'), the present indicative forms of haber (habih and hai 'you have'), and the present indicative of ser (soi, eríh and erei 'you are'), without resorting to any ad hoc rules.

Second-person plural

[edit]In Standard European Spanish the plural of tú is vosotros and the plural of usted is ustedes. In Hispanic America vosotros is not used, and the plural of both tú and usted is ustedes. This means that speaking to a group of friends a Spaniard will use vosotros, while a Latin American Spanish speaker will use ustedes. Although ustedes is semantically a second-person form, it is treated grammatically as a third-person plural form because it originates from the term vuestras mercedes ('your [pl.] mercies,' sing. vuestra merced).

The only vestiges of vosotros in the Americas are boso/bosonan in Papiamento and the use of vuestro/a in place of sus (de ustedes) as second person plural possessive in the Cusco region of Peru.

In very formal contexts, however, the vosotros conjugation can still be found. An example is the Mexican national anthem, which contains such forms as aprestad and empapad.

The plural of the Colombian (Cundi-Boyacense Plateau) sumercé is sumercés/susmercedes, from sus mercedes ('your mercies').

In some parts of Andalusia (the lands around the Guadalquivir river and western Andalusia), the usage is what is called ustedes-vosotros: the pronoun ustedes is combined with the verb forms for vosotros. However, this sounds extremely colloquial and most Andalusians prefer to use each pronoun with its correct form.

In Ladino, vosotros is still the only second person plural pronoun, since ustedes does not exist.

Second-person verb forms

[edit]Each second-person pronoun has its historically corresponding verb forms. The formal usted and ustedes, although semantically second person, take verb forms identical with those of the third person, singular and plural respectively, since they are derived from the third-person expressions vuestra merced and vuestras mercedes ('your grace[s]'). The forms associated with the singular vos can generally be derived from those for the plural vosotros by deleting the palatal semivowel of the ending (vosotros habláis > vos hablás, 'you speak'; vosotros coméis > vos comés, 'you eat').

General statements about the use of voseo in different localities should be qualified by the note that individual speakers may be inconsistent in their usage, and that isoglosses rarely coincide with national borders. That said, a few assertions can be made:

- "Full" voseo (involving both pronoun and verb—vos comés, 'you eat') is characteristic of two zones: that of Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay and that of Central America and the Mexican state of Chiapas.

- Pronominal voseo (vos tienes, vos dices, etc. but vos sos) is common in Santiago del Estero Province, Argentina

- "Full" voseo coexists with the use of tú and its verb forms (e.g. tú comes) in Colombia and Ecuador, and in parts of Colombia also with usted (with its standard verb forms) as a familiar form.

- In Chile there is coexistence of three usages:

- tú and its verb forms (tú comes);

- "full" voseo with uniquely Chilean voseo verb endings (-ái, -ís, and -ís respectively for -ar, -er, and -ir verbs: vos hablái—'you speak', vos comís—"you eat", vos vivís—'you live'); and

- verbal voseo with the Chilean verb endings (tú hablái, tú comís, etc.).

- "Full" voseo coexists with verbal voseo (tú comés) in Uruguay.

- In Venezuela's Zulia State and parts of the state of Falcón there is no deletion of the palatal semivowel, creating vos coméis, vos habláis, and vos seáis. In Trujillo State, the "voseo" is like that of Argentina, with the exception of the imperative mood, which is like that of the standard tú.[49]

- Voseo is absent from the Spanish of Spain, and from most of Mexico, Peru, and the islands of the Caribbean.

As for the second person familiar plural, it can be said that northern and central Spain use vosotros and its verb forms (vosotros habláis, 'you [pl.] speak'), while the rest of the Spanish-speaking world merges the familiar and formal in ustedes (ustedes hablan). Usage in western Andalusia includes the use of ustedes with the traditional vosotros verb form (ustedes habláis).

In Ladino, the second-person pronouns are quite different from those of Spain and Latin America. The forms usted and ustedes had not yet appeared in 1492 when the Jews were expelled from Spain. Speakers of Ladino still use vos as it was used in the Middle Ages (as a singular) to address people higher on the social ladder. And vosotros is the only second person plural pronoun. In Ladino the formal singular for 'you speak' is vos avláis (pronounced [aˈvlaʃ], and the same verb form serves for the plural, both formal and familiar: vosotros avláis ([voˈzotros aˈvlaʃ]). The subjunctive 'that you lose (formal singular)' is que vos pedráis ([ke vos peˈdraʃ]), while the plural (both formal and familiar) is que vosotros pedráis ([ke voˈzotros peˈdraʃ]). The formal singular imperative ('come') is venid or vení, and the same form serves as the plural imperative, both formal and familiar.

Third-person object pronouns

[edit]

In many dialects in northern and central Spain, including that of Madrid, the indirect object pronouns le and les may be used in place of the direct object pronouns lo, la, los, and las in a phenomenon known as leísmo. Leísmo typically occurs when the direct object refers to a person or personalized thing, such as a pet, and is most commonly used for male direct objects. The opposite phenomenon also occurs in the same regions of Spain and is known as loísmo or laísmo. In loísmo, the direct object pronouns lo and los are used in contexts where the indirect object pronouns le and les would normally be prescribed; this usually occurs with a male indirect object. In laísmo, la and las are used instead of le and les when referring to a female indirect object.

Verb tenses for past events

[edit]In a broad sense, when expressing an action viewed as finished in the past, speakers (and writers) in most of Spain use the perfect tense—e.g. he llegado *'I have arrived')—more often than their American counterparts, while Spanish-speakers in the Americas more often use the preterite (llegué 'I arrived').[50]

The perfect is also called the "present perfect" and, in Spanish, pasado perfecto or pretérito perfecto compuesto. It is described as a "compound" tense (compuesto in Spanish) because it is formed with the auxiliary verb haber plus a main verb.

The preterite, also called the "simple past" and, in Spanish, pretérito indefinido or pretérito perfecto simple, is considered a "simple" tense because it is formed of a single word: the verb stem with an inflectional ending for person, number, etc.

The choice between preterite and perfect, according to prescriptive grammars from both Spain[51][52] and the Americas,[53] is based on the psychological time frame—whether expressed or merely implied—in which the past action is embedded. If that time frame includes the present moment (i.e. if the speaker views the past action as somehow related to the moment of speaking), then the recommended tense is the perfect (he llegado). But if the time frame does not include the present—if the speaker views the action as only in the past, with little or no relation to the moment of speaking—then the recommended tense is the preterite (llegué). This is also the real spontaneous usage in most of Spain.

Following this criterion, an explicit time frame such as hoy ('today') or este año ('this year') includes the present and thus dictates the compound tense: Este año he cantado ('I have sung this year'). Conversely, a time frame such as ayer ('yesterday') or la semana pasada ('last week') does not include the present and therefore calls for the preterite: La semana pasada canté ('I sang last week').

However, in most of the Americas, and in the Canary Islands, the preterite is used for all actions viewed as completed in the past. It tends to be used in the same way in those parts of Spain where the local languages and vernaculars do not have compound tenses, that is, the Galician-speaking area and the neighbouring Astur-Leonese-speaking area.

In most of Spain, the compound tense is preferred in most cases when the action described is close to the present moment:

- He viajado a (los) Estados Unidos. ('I have [just] traveled to (the) United States')

- Cuando he llegado, la he visto. ('When I arrived, I saw her')

- ¿Qué ha pasado? ('What just happened?')

Prescriptive norms would rule out the compound tense in a cuando-clause, as in the second example above.

Meanwhile, in Galicia, León, Asturias, Canary Islands and the Americas, speakers follow the opposite tendency, using the simple past tense in most cases, even if the action takes place at some time close to the present:

- Ya viajé a (los) Estados Unidos. ('I [have already] traveled to (the) United States')

- Cuando llegué, la vi. ('When I arrived, I saw her')

- ¿Qué pasó? ('What just happened?')

In Latin America one could say, "he viajado a España varias veces" ('I have traveled to Spain several times'), to express a repeated action, as in English. But to say El año pasado he viajado a España would sound ungrammatical (as it would also be in English to say "last year, I have traveled to Spain", as last year implies that the relevant time period does not include the present). In Spain, speakers use the compound tense when the period of time considered has not ended, as in he comprado un coche este año ('I have bought a car this year'). Meanwhile, a Latin American Spanish speaker is more likely to say, "compré un carro este año" ('I bought a car this year').

Vocabulary

[edit]Different regional varieties of Spanish vary in terms of vocabulary as well. This includes both words that exist only in certain varieties (especially words borrowed from indigenous languages of the Americas), and words that are used differently in different areas. Among words borrowed from indigenous languages are many names for food, plants and animals, clothes, and household object, such as the following items of Mexican Spanish vocabulary borrowed from Nahuatl.[2]

| Word | English translation |

|---|---|

| camote | sweet potato |

| pipián | stew |

| chapulín | grasshopper |

| huipil | blouse |

| metate | grinder, mortar and pestle |

In addition to loan words, there are a number of Spanish words that have developed distinct senses in different regional dialects. That is, for certain words a distinct meaning, either in addition to the standard meaning or in place of it, exists in some varieties of Spanish.

| Word | Standard meaning | Regional meaning |

|---|---|---|

| almacén | warehouse, department store | grocery store (Rioplatense Spanish, Chilean Spanish, Andean Spanish)[54] |

| colectivo | collective | bus (Argentine Spanish originally 'collective taxi', Chilean Spanish, Bolivian Spanish)[54]) |

| cuadra | stable, pigsty | city block (United States Spanish)[54] |

| chaqueta | jacket | (vulgar) male masturbation (Central American Spanish)[55] |

| coger | to take, to catch, to start, to feel | (vulgar) to fuck, have sexual relations (Rioplatense Spanish and Mexican Spanish)[56] |

| concha | shell, tortoiseshell | (vulgar) cunt (Rioplatense Spanish, Chilean Spanish, Andean Spanish)[54] |

| peloteo | knock-up (in tennis), warm up | fawning, adulation (Peninsular Spanish)[54] |

Mutual intelligibility

[edit]The different dialects and accents do not block cross-understanding among relatively educated speakers. Meanwhile, the basilects have diverged more. The unity of the language is reflected in the fact that early imported sound films were dubbed into one version for the entire Spanish-speaking market. Currently, films not originally in Spanish (usually Hollywood productions) are typically dubbed separately into two or sometimes three accents: one for Spain (standardized Peninsular Spanish without regional terms and pronunciations), and for the Americas, either just one (Mexican), or two: a Mexican one for most of the Americas (using a neutral standardized accent without regionalisms) and one in Rioplatense Spanish for Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay. [citation needed] Some high-budget productions, however, such as the Harry Potter film series, have had dubs in three or more of the major accents. On the other hand, productions from another Spanish-language country are seldom dubbed. Exceptionally, the made-in-Spain animated features Dogtanian and the Three Muskehounds and The World of David the Gnome, as well as TV serials from the Andean countries such as Karkú (Chile), have had a Mexican dub. The popularity of telenovelas and music familiarizes the speakers with other accents of Spanish.

Prescription and a common cultural and literary tradition, among other factors, have contributed to the formation of a loosely defined register which can be termed Standard Spanish (or "Neutral Spanish"), which is the preferred form in formal settings, and is considered indispensable in academic and literary writing, the media, etc. This standard tends to disregard local grammatical, phonetic and lexical peculiarities, and draws certain extra features from the commonly acknowledged canon, preserving (for example) certain verb tenses considered "bookish" or archaic in most other dialects.

Mutual intelligibility in Spanish does not necessarily mean a translation is wholly applicable in all Spanish-speaking countries, especially when conducting health research that requires precision. For example, an assessment of the applicability of QWB-SA's Spanish version in Spain showed that some translated terms and usage applied US-specific concepts and regional lexical choices and cannot be successfully implemented without adaptation.[57]

See also

[edit]Cants and argots

[edit]- Bron of migrant merchants and artisans of Asturias and León

- Caló language of Gitanos

- Caló of Chicanos

- Coa of Chilean criminals

- Cheli of Madrid

- Gacería of Cantalejo, Spain

- Germanía of Spanish Golden Century criminals

- Lunfardo of Porteño Spanish

- Parlache originated in the city of Medellin

Mixes with other languages

[edit]- Spanish-based creole languages

- Annobonese language of Annobón Province and Bioko, Equatorial Guinea

- Belgranodeutsch of Buenos Aires

- Castrapo of Galicia

- Amestao of Asturias

- Chavacano of the Philippines

- Cocoliche of Buenos Aires

- Frespañol of French–Spanish contact

- Judaeo-Spanish, also known as Ladino, the language of the Sephardic Jews

- Llanito of Gibraltar

- Palenquero of Colombia

- Papiamento of Aruba, Curaçao and Bonaire

- Pichinglis of Bioko, Equatorial Guinea

- Portuñol of the Brazilian border

- Spanglish of the United States of America

- Jopara language in Paraguay with Guarani language

Other

[edit]- History of the Spanish language

- Spanish phonology

- Andalusian Spanish

- Castilian Spanish

- Central American Spanish

- South American Spanish

- Equatoguinean Spanish

- Philippine Spanish

Notes

[edit]- ^ Alemany, Luis (2021-11-30). "El español de Chile: la gran olla a presión del idioma". El Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2022-06-01.

- ^ a b Cotton & Sharp (1988)

- ^ Lope Blanch (1972:222)

- ^ Delforge (2008)

- ^ Lipski (2012:3)

- ^ Lipski (2018:502)

- ^ Lipski (2012:2)

- ^ Lipski (2018:501)

- ^ Hualde, José Ignacio; Olarrea, Antxon; Escobar, Anna María; Travis, Catherine E.; Sanz, Cristina (2021). "Variación lingüística en español". Introducción a la lingüística hispánica (in Spanish) (3rd ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 380–432. ISBN 9781108770293.

- ^ Lipski, John (2004). "The Spanish Language of Equatorial Guinea" (PDF). Arizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural Studies. 8 (1): 115–130. doi:10.1353/hcs.2011.0376. ISSN 1934-9009. S2CID 144501371.

- ^ Şaul, Mahir; Hualde, José Ignacio (April 2011). "Istanbul Judeo-Spanish". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 41 (1): 89–110. doi:10.1017/S0025100310000277. ISSN 1475-3502.

- ^ HARRIS, TRACY K. (2009). "Reasons for the decline of Judeo-Spanish". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 1982 (37): 71–98. doi:10.1515/ijsl.1982.37.71. ISSN 1613-3668. S2CID 143255709.

- ^ González Bueno (1993)

- ^ Whitley (2002:26)

- ^ Hualde (2005:298)

- ^ Navarro Tomás (1939)

- ^ Alonso, Canellada & Zamora Vicente (1950)

- ^ a b c Canfield (1981)

- ^ Penny, Ralph (1991). "El origen asturleonés de algunos fenómenos andaluces y americanos" (PDF). Lletres asturianes: Boletín Oficial de l'Academia de la Llingua Asturiana (in Spanish). 39: 33–40. ISSN 0212-0534. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ D'Introno, Del Teso & Weston (1995:294)

- ^ Canfield (1981:13)

- ^ Hualde, José Ignacio (2005). "Quasi-phonemic contrasts in Spanish". WCCFL 23: Proceedings of the 23rd West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press. pp. 374–398.

- ^ Hualde (2005:184).

- ^ Lipski, John M. (1990), Spanish Taps and Trills: Phonological Structure of an Isolated Position (PDF)

- ^ Canfield (1981:7–8)

- ^ Penny (2000:157)

- ^ Lipski (1994:333)

- ^ Canfield (1981:78)

- ^ Navarro-Tomás, T. (1948). "El español en Puerto Rico". Contribución a la geografía lingüística latinoamericana. Río Piedras: Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, pp. 91-93.

- ^ López-Morales, H. (1983). Estratificación social del español de San Juan de Puerto Rico. México: UNAM.

- ^ López-Morales, H. (1992). El español del Caribe. Madrid: MAPFRE, p. 61.

- ^ Jiménez-Sabater, M. (1984). Más datos sobre el español de la República Dominicana. Santo Domingo: Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo, p. 87.

- ^ José Ignacio Hualde, Jon Ortiz De Urbina (2003). Grammar of Basque. Walter de Gruyter, p. 30.

- ^ Navarro Tomás (2004)

- ^ "División silábica y ortográfica de palabras con "tl"". Real Académia Española (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Hualde, José Ignacio; Carrasco, Patricio (2009). "/tl/ en español mexicano. ¿Un segmento o dos?" (PDF). Estudios de Fonética Experimental (in Spanish). XVIII: 175–191. ISSN 1575-5533.

- ^ Zamora, Juan Clemente (1982-01-01). "Amerindian loanwords in general and local varieties of American Spanish". WORD. 33 (1–2): 159–171. doi:10.1080/00437956.1982.11435730. ISSN 0043-7956.

- ^ a b Hualde (2005:130)

- ^ Lipski (2012:8)

- ^ Bradley, Travis G.; Smith, Jason (2015). "The Phonology-Morphology Interface in Judeo-Spanish Diminutive Formation: A Lexical Ordering and Subcategorization Approach". Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics. 4 (2): 247–300. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.387.8195. doi:10.1515/shll-2011-1103. ISSN 2199-3386. S2CID 10478601.

- ^ Lipski, John M. (2011). "Socio-Phonological Variation in Latin American Spanish". In Díaz-Campos, Manuel (ed.). The handbook of Hispanic sociolinguistics. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 72–97. doi:10.1002/9781444393446.ch4. ISBN 9781405195003.

- ^ O'Rourke, Erin (2004). "Peak placement in two regional varieties of Peruvian Spanish intonation". In Auger, Julie; Clements, J. Clancy; Vance, Barbara (eds.). Contemporary approaches to Romance linguistics: selected papers from the 33rd Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages (LSRL), Bloomington, Indiana, April 2003. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins. pp. 321–342. ISBN 9789027247728.

- ^ O'Rourke, Erin (2012). "Intonation in Spanish". In Hualde, José Ignacio; Olarrea, Antxon; O'Rourke, Erin (eds.). The handbook of Hispanic linguistics. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 173–191. doi:10.1002/9781118228098.ch9. ISBN 9781405198820.

- ^ Kany (1951:55–91)

- ^ Kany (1951:56–57)

- ^ Corominas (1987)

- ^ Kany (1951:58–63)

- ^ "3235 - Google Drive". Retrieved 2015-05-31.

- ^ Kany (1951:161–164)

- ^ Seco (1986:302)

- ^ Real Academia Española (1973:465 and 468)

- ^ Bello (1903:134)

- ^ a b c d e Webster's New World Concise Spanish Dictionary (2006)

- ^ Velázquez Spanish and English Dictionary: Pocket Edition (2006)

- ^ Miyara (2001)

- ^ Congost-Maestre, Nereida (2020-04-30). Sha, Mandy (ed.). Sociocultural issues in adapting Spanish health survey translation: The case of the QWB-SA (Chapter 10) in The Essential Role of Language in Survey Research. RTI Press. pp. 203–220. doi:10.3768/rtipress.bk.0023.2004. ISBN 978-1-934831-24-3.

Bibliography

[edit]- Real Academia Española (1973), Esbozo de una nueva gramática de la lengua española, Madrid: Espasa-Calpe

- Alonso, Dámaso; Canellada, María Josefa; Zamora Vicente, Alonso (1950), "Vocales andaluzas", Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica, 4: 209–230, doi:10.24201/nrfh.v4i3.159

- Baquero, Julia M.; Westphal, Germán F. (2014), "Un análisis sincrónico del voseo verbal chileno y rioplatense" (PDF), Forma y Función, 27 (2): 11–40, doi:10.15446/fyf.v27n2.47558

- Bello, Andrés (1903), Gramática de la lengua castellana destinada al uso de los americanos, Paris: Roger & Chervoviz

- Canfield, D[elos] Lincoln (1981), Spanish Pronunciation in the Americas, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 9780226092638

- Corominas, Joan (1987), Breve diccionario etimológico de la lengua castellana, Madrid: Gredos

- Cotton, Eleanor Greet; Sharp, John M. (1988), Spanish in the Americas, Washington: Georgetown University Press, ISBN 0-87840-360-4

- Delforge, Ann Marie (2008), "Unstressed Vowel Reduction in Andean Spanish" (PDF), in Colantoni, Laura; Steele, Jeffrey (eds.), Selected Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Laboratory Approaches to Spanish Phonology, Somerville, Mass., USA: Cascadilla, pp. 107–124

- D'Introno, Francesco; Del Teso, Enrique; Weston, Rosemary (1995), Fonética yfonología actual del español, Madrid: Cátedra

- González Bueno, Manuela (1993), "Variaciones en el tratamiento de las sibilantes: Inconsistencia en el seseo sevillano: Un enfoque sociolingüístico", Hispania, 76 (2): 392–398, doi:10.2307/344719, hdl:1808/17759, JSTOR 344719

- Hualde, José Ignacio (2005), The Sounds of Spanish, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521545389

- Kany, Charles E. (1951), American-Spanish Syntax, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 9780758125439

- Lipski, John M. (1994), Latin American Spanish, London: Longman, ISBN 9780582087613

- Lipski, John M. (2012). "Geographical and Social Varieties of Spanish: An Overview" (PDF). In Hualde, José Ignacio; Olarrea, Antxon; O'Rourke, Erin (eds.). The Handbook of Hispanic Linguistics. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 1–26. doi:10.1002/9781118228098.ch1. ISBN 9781405198820.

- Lipski, John M. (2018). "Dialects of Spanish and Portuguese" (PDF). In Boberg, Charles; Nerbonne, John; Watt, Dominic (eds.). The handbook of dialectology. Hoboken, NJ. pp. 498–509. doi:10.1002/9781118827628.ch30. ISBN 9781118827550.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lope Blanch, Juan M. (1972), "En torno a las vocales caedizas del español mexicano" (PDF), Estudios sobre el español de México, Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, pp. 53–73

- Miyara, Alberto J. (2001), Diccionario argentino-español para españoles, (Online)

- Moreno Fernández, Francisco (2009), La lengua española en su geografía, Madrid: Arco/Libros, ISBN 9788476357835

- Navarro Tomás, Tomás (1939), "Desdoblamiento de fonemas vocálicos", Revista de Filología Hispánica, 1: 165–167

- Navarro Tomás, Tomás (2004), Manual de pronunciación española (28th ed.), Madrid: Concejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, ISBN 9788400070960

- Penny, Ralph J. (2000). Variation and change in Spanish. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139164566. ISBN 0521780454. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Seco, Manuel (1986), Diccionario de dudas y dificultades de la lengua española, Madrid: Espasa-Calpe

- Sorenson, Travis D. (2021). The Dialects of Spanish: A Lexical Introduction (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108924580. ISBN 9781108831789.

- Velázquez Spanish and English Dictionary: Pocket Edition, El Monte, Cal., USA: Velázquez Press, 2006, ISBN 1-594-95003-2

- Webster's New World Concise Spanish Dictionary, Indianapolis: Wiley, 2006, ISBN 0-471-74836-6

- Whitley, M[elvin] Stanley (2002), Spanish-English Contrasts, Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, ISBN 0878403817

Further reading

[edit]- Alonso Zamora Vicente, Dialectología Española (Madrid: Editorial Gredos, 1960) is highly detailed.

External links

[edit]- Isogloss maps of phonetic variants in the Iberian Peninsula

- Map of Spanish dialects in the Iberian Peninsula

- Costa Rican Spanish Dictionary

- Spanish learning site with Argentinian speakers

- Hispanic American Dictionary with variants for every country

- Spanish dialects, pronunciation maps

- COSER, Audible Corpus of Spoken Rural Spanish