William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone | |

|---|---|

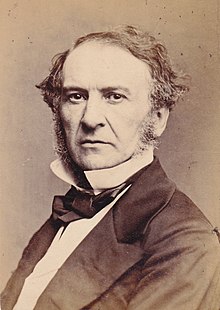

Gladstone in 1892 | |

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |

| In office 15 August 1892 – 2 March 1894 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Salisbury |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Rosebery |

| In office 1 February 1886 – 21 July 1886 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Salisbury |

| Succeeded by | The Marquess of Salisbury |

| In office 23 April 1880 – 9 June 1885 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Disraeli |

| Succeeded by | The Marquess of Salisbury |

| In office 3 December 1868 – 17 February 1874 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Disraeli |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Disraeli |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

| In office 28 April 1880 – 16 December 1882 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Stafford Northcote |

| Succeeded by | Hugh Childers |

| In office 11 August 1873 – 17 February 1874 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Robert Lowe |

| Succeeded by | Stafford Northcote |

| In office 18 June 1859 – 26 June 1866 | |

| Prime Minister | The Viscount Palmerston The Earl Russell |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Disraeli |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Disraeli |

| In office 28 December 1852 – 28 February 1855 | |

| Prime Minister | The Earl of Aberdeen |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Disraeli |

| Succeeded by | George Cornewall Lewis |

| Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands | |

| In office 25 January 1859 – 17 February 1859 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | Sir John Young |

| Succeeded by | Sir Henry Knight Storks |

| Additional positions | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 29 December 1809 62 Rodney Street, Liverpool, Lancashire, England |

| Died | 19 May 1898 (aged 88) Hawarden Castle, Flintshire, Wales |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey |

| Political party | Liberal (1859–1898) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | 8; including William, Helen, Henry and Herbert |

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford |

| Cabinet | |

| Signature |  |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Liberalism in the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarianism |

|---|

William Ewart Gladstone FRS FSS (/ˈɡlædstən/ GLAD-stən; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom for 12 years, spread over four non-consecutive terms (the most of any British prime minister) beginning in 1868 and ending in 1894. He also was Chancellor of the Exchequer four times, for over 12 years. He was a Member of Parliament (MP) for 60 years, from 1832 to 1845 and from 1847 to 1895; during that time he represented a total of five constituencies.

Gladstone was born in Liverpool to Scottish parents. He first entered the House of Commons in 1832, beginning his political career as a High Tory, a grouping that became the Conservative Party under Robert Peel in 1834. Gladstone served as a minister in both of Peel's governments, and in 1846 joined the breakaway Peelite faction, which eventually merged into the new Liberal Party in 1859. He was chancellor under Lord Aberdeen (1852–1855), Lord Palmerston (1859–1865) and Lord Russell (1865–1866). Gladstone's own political doctrine – which emphasised equality of opportunity and opposition to trade protectionism – came to be known as Gladstonian liberalism. His popularity amongst the working-class earned him the sobriquet "The People's William".

In 1868, Gladstone became prime minister for the first time. Many reforms were passed during his first ministry, including the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland and the introduction of secret voting. After electoral defeat in 1874, Gladstone resigned as leader of the Liberal Party. From 1876 he began a comeback based on opposition to the Ottoman Empire's reaction to the Bulgarian April Uprising. His Midlothian Campaign of 1879–1880 was an early example of many modern political campaigning techniques.[1][2] After the 1880 general election, Gladstone formed his second ministry (1880–1885), which saw the passage of the Third Reform Act as well as crises in Egypt (culminating in the Fall of Khartoum) and Ireland, where his government passed repressive measures but also improved the legal rights of Irish tenant farmers.

Back in office in early 1886, Gladstone proposed home rule for Ireland but was defeated in the House of Commons. The resulting split in the Liberal Party helped keep them out of office – with one short break – for 20 years. Gladstone formed his last government in 1892, at the age of 82. The Government of Ireland Bill 1893 passed through the Commons but was defeated in the House of Lords in 1893, after which Irish Home Rule became a lesser part of his party's agenda. Gladstone left office in March 1894, aged 84, as both the oldest person to serve as prime minister and the only prime minister to have served four non-consecutive terms. He left Parliament in 1895 and died three years later.

Gladstone was known affectionately by his supporters as "The People's William" or the "G.O.M." ("Grand Old Man", or, to political rivals "God's Only Mistake").[3] Historians often rank Gladstone as one of the greatest prime ministers in British history.[4][5][6][7]

Early life

[edit]Born on 29 December 1809[8] in Liverpool, at 62 Rodney Street, William Ewart Gladstone was the fourth son of the wealthy merchant, planter and Tory politician John Gladstone, and his second wife, Anne MacKenzie Robertson.[9] He was named after a close friend of his father, William Ewart, another Liverpool merchant and the father of William Ewart, later a Liberal politician.[10] In 1835, the family name was changed from Gladstones to Gladstone by royal licence. His father was made a baronet, of Fasque and Balfour, in 1846.[9]

Although born and raised in Liverpool, William Gladstone was of purely Scottish ancestry.[11] His grandfather Thomas Gladstones was a prominent merchant from Leith, and his maternal grandfather, Andrew Robertson, was Provost of Dingwall and a Sheriff-Substitute of Ross-shire.[9] His biographer John Morley described him as "a highlander in the custody of a lowlander", and an adversary as "an ardent Italian in the custody of a Scotsman". One of his earliest childhood memories was being made to stand on a table and say "Ladies and gentlemen" to the assembled audience, probably at a gathering to promote the election of George Canning as MP for Liverpool in 1812. In 1814, young "Willy" visited Scotland for the first time, as he and his brother John travelled with their father to Edinburgh, Biggar and Dingwall to visit their relatives. Willy and his brother were both made freemen of the burgh of Dingwall.[12] In 1815, Gladstone also travelled to London and Cambridge for the first time with his parents. Whilst in London, he attended a service of thanksgiving with his family at St Paul's Cathedral following the Battle of Waterloo, where he saw the Prince Regent.[13]

William Gladstone was educated from 1816 to 1821 at a preparatory school at the vicarage of St. Thomas' Church at Seaforth, close to his family's residence, Seaforth House.[11] In 1821, William followed in the footsteps of his elder brothers and attended Eton College before matriculating in 1828 at Christ Church, Oxford, where he read Classics and Mathematics, although he had no great interest in the latter subject. In December 1831, he achieved the double first-class degree he had long desired. Gladstone served as President of the Oxford Union, where he developed a reputation as an orator, which followed him into the House of Commons. At university, Gladstone was a Tory and denounced Whig proposals for parliamentary reform in a famous debate at the Oxford Union in May 1831. On the second day of the three-day debate on the Whig Reform Bill Gladstone moved the motion:

That the Ministry has unwisely introduced, and most unscrupulously forwarded, a measure which threatens not only to change the form of our Government, but ultimately to break up the very foundations of social order, as well as materially to forward the views of those who are pursuing the project throughout the civilised world.[14]

Gladstone's 45-minute speech made a great impression on those present and his Amendment carried 94 votes to 38. Among those impressed was Lord Lincoln, who told his father the Duke of Newcastle about it, and it was through this recommendation that the Duke offered Gladstone the safe seat of Newark which he then controlled.

Following the success of his double first, William travelled with his brother John on a Grand Tour of western Europe.

Although Gladstone entered Lincoln's Inn in 1833, with intentions of becoming a barrister, by 1839 he had requested that his name should be removed from the list because he no longer intended to be called to the Bar.[11]

In September 1842 he lost the forefinger of his left hand in an accident while reloading a gun. Thereafter he wore a glove or finger sheath (stall).

House of Commons

[edit]First term

[edit]When Gladstone was 22 the Duke of Newcastle, a Conservative party activist, provided him with one of two seats at Newark where he controlled about a fourth of the very small electorate. The Duke spent thousands of pounds entertaining the voters. Gladstone displayed remarkably strong technique as a campaigner and stump speaker.[15] He won his seat at the 1832 United Kingdom general election with 887 votes.[16] After new bills to protect child workers were proposed following the publication of the Sadler report, he voted against the 1833 Factory Acts that would regulate the hours of work and welfare of minors employed in cotton mills.[17]

Opposition to the opium trade

[edit]Gladstone was an intense opponent of the opium trade.[18][19] Referring to the opium trade between British India and Qing China, Gladstone described it as "infamous and atrocious".[20] Gladstone emerged as a fierce critic of the Opium Wars, which Britain waged to re-legalise the British opium trade into China, which had been made illegal by the Chinese government.[21] He publicly lambasted the wars as "Palmerston's Opium War" and said that he felt "in dread of the judgements of God upon England for our national iniquity towards China" in May 1840.[22] A famous speech was made by Gladstone in Parliament against the First Opium War.[23][24] Gladstone criticised it as "a war more unjust in its origin, a war more calculated in its progress to cover this country with permanent disgrace".[25] His hostility to opium stemmed from the effects of opium upon his sister Helen.[26][27] Before 1841, Gladstone was reluctant to join the Peel government because of the First Opium War, which Palmerston had brought on.[28]

Minister under Peel (1841–1846)

[edit]Gladstone was re-elected in 1841. In the second ministry of Robert Peel, he served as President of the Board of Trade (1843–1845).[8]

Gladstone was responsible for the Railways Act 1844, regarded by historians as the birth of the regulatory state, of network industry regulation, of rate of return regulation, and telegraph regulation. Examples of its foresight are the clauses empowering the government to take control of railways in times of war, the concept of Parliamentary trains, limited in cost to a penny a mile, of universal service, and of control of the recently invented electric telegraph which ran alongside railway lines. Railways were the largest investment (as a percentage of GNP) in human history[dubious – discuss] and this Bill the most heavily lobbied in Parliamentary history[dubious – discuss]. Gladstone succeeded in guiding the Act through Parliament at the height of the railway bubble.[29]

Gladstone became concerned with the situation of "coal whippers". These were the men who worked on London docks, "whipping" in baskets from ships to barges or wharves all incoming coal from the sea. They were called up and relieved through public houses, so a man could not get this job unless he had the favourable opinion of the publican, who looked most favourably upon those who drank. The man's name was written down and the "score" followed. Publicans issued employment solely on the capacity of the man to pay, and men were often drunk when they left the pub to work. They spent their savings on drinks to secure the favourable opinion of publicans and further employment.

Gladstone initiated the Coal Vendors Act of 1843, which set up a central office for employment. When that Act expired in 1856, a Select Committee was appointed by the Lords in 1857 to look into the question. Gladstone gave evidence to the committee, stating: "I approached the subject in the first instance as I think everyone in Parliament of necessity did, with the strongest possible prejudice against the proposal [to interfere]; but the facts stated were of so extraordinary and deplorable a character, that it was impossible to withhold attention from them. Then the question being whether legislative interference was required I was at length induced to look at a remedy of an extraordinary character as the only one I thought applicable to the case ... it was a great innovation".[30] Looking back in 1883, Gladstone wrote that "In principle, perhaps my Coalwhippers Act of 1843 was the most Socialistic measure of the last half century".[31]

He resigned in 1845 over the Maynooth Grant issue, which was a matter of conscience for him.[32] To improve relations with the Catholic Church, Peel's government proposed increasing the annual grant paid to the Maynooth Seminary for training Catholic priests in Ireland. Gladstone, who had previously argued in a book that a Protestant country should not pay money to other churches, nevertheless supported the increase in the Maynooth grant and voted for it in Commons, but resigned rather than face charges that he had compromised his principles to remain in office. After accepting Gladstone's resignation, Peel confessed to a friend, "I really have great difficulty sometimes in exactly comprehending what he means".[33] In December 1845, Gladstone returned to Peel's government as Colonial Secretary. The Dictionary of National Biography notes: "As such, he had to stand for re-election, but the strong protectionism of the Duke of Newcastle, his patron in Newark, meant that he could not stand there and no other seat was available. Throughout the corn law crisis of 1846, therefore, Gladstone was in the highly anomalous and possibly unique position of being a secretary of state without a seat in either house and thus unanswerable to parliament."[34]

Return to the backbenches (1846–1851)

[edit]When Peel's government fell in 1846, Gladstone and other Peel loyalists followed their leader in separating from the protectionist Conservatives; instead offering tentative support to the new Whig prime minister Lord John Russell, with whom Peel had cooperated over the repeal of the Corn Laws. After Peel's death in 1850, Gladstone emerged as the leader of the Peelites in the House of Commons. He was re-elected for the University of Oxford (i.e. representing the MA graduates of the university) at the General Election in 1847 – Peel had once held this seat but had lost it because of his espousal of Catholic Emancipation in 1829. Gladstone became a constant critic of Lord Palmerston.[35]

In 1847 Gladstone helped to establish Glenalmond College, then The Holy and Undivided Trinity College at Glenalmond. The school was set up as an episcopal foundation to spread the ideas of Anglicanism in Scotland, and to educate the sons of the gentry.[36]

As a young man Gladstone had treated his father's estate, Fasque, in Kincardineshire, southwest of Aberdeen, as home, but as a younger son he would not inherit it. Instead, from the time of his marriage, he lived at his wife's family's estate at Hawarden in Flintshire, Wales. He never actually owned Hawarden, which belonged first to his brother-in-law Sir Stephen Glynne, and was then inherited by Gladstone's eldest son in 1874. During the late 1840s, when he was out of office, he worked extensively to turn Hawarden into a viable business.[37]

In 1848 he founded the Church Penitentiary Association for the Reclamation of Fallen Women. In May 1849 he began his most active "rescue work" and met prostitutes late at night on the street, in his house or in their houses, writing their names in a private notebook. He aided the House of Mercy at Clewer near Windsor (which exercised extreme in-house discipline) and spent much time arranging employment for ex-prostitutes. In a "Declaration" signed on 7 December 1896 and only to be opened after his death, Gladstone wrote, "I desire to record my solemn declaration and assurance, as in the sight of God and before His Judgement Seat, that at no period of my life have I been guilty of the act which is known as that of infidelity to the marriage bed."[38]

In 1850–51 Gladstone visited Naples, Italy, for the benefit of his daughter Mary's eyesight. Giacomo Lacaita, a legal adviser to the British embassy, was at the time imprisoned by the Neapolitan government, as were other political dissidents. Gladstone became concerned about the political situation in Naples and the arrest and imprisonment of Neapolitan liberals. In February 1851 Gladstone visited the prisons where thousands of them were held and was extremely outraged. In April and July, he published two Letters to the Earl of Aberdeen against the Neapolitan government and responded to his critics in An Examination of the Official Reply of the Neapolitan Government in 1852. Gladstone's first letter described what he saw in Naples as "the negation of God erected into a system of government".[39]

Chancellor of the Exchequer (1852–1855)

[edit]

In 1852, following the appointment of Lord Aberdeen as prime minister, head of a coalition of Whigs and Peelites, Gladstone became Chancellor of the Exchequer. The Whig Sir Charles Wood and the Tory Disraeli had both been perceived to have failed in the office and so this provided Gladstone with a great political opportunity.[40]

His first budget in 1853 almost completed the work begun by Peel eleven years before in simplifying Britain's tariff of duties and customs.[41] 123 duties were abolished and 133 duties were reduced.[42] The income tax had legally expired but Gladstone proposed to extend it for seven years to fund tariff reductions:

We propose, then, to re-enact it for two years, from April 1853 to April 1855, at the rate of 7d. in the £; from April 1855, to enact it for two more years at 6d. in the £; and then for three years more ... from April 1857, at 5d. Under this proposal, on 5 April 1860, the income tax will by law expire.[43]

Gladstone wanted to maintain a balance between direct and indirect taxation and to abolish income tax. He knew that its abolition depended on a considerable retrenchment in government expenditure. He therefore increased the number of people eligible to pay it by lowering the threshold from £150 to £100. The more people that paid income tax, Gladstone believed, the more the public would pressure the government into abolishing it.[44] Gladstone argued that the £100 line was "the dividing line ... between the educated and the labouring part of the community" and that therefore the income taxpayers and the electorate were to be the same people, who would then vote to cut government expenditure.[44]

The budget speech (delivered on 18 April), nearly five hours long, raised Gladstone "at once to the front rank of financiers as of orators".[45] Colin Matthew has written that Gladstone "made finance and figures exciting, and succeeded in constructing budget speeches epic in form and performance, often with lyrical interludes to vary the tension in the Commons as the careful exposition of figures and argument was brought to a climax".[46] The contemporary diarist Charles Greville wrote of Gladstone's speech:

... by universal consent it was one of the grandest displays and most able financial statement that ever was heard in the House of Commons; a great scheme, boldly, skilfully, and honestly devised, disdaining popular clamour and pressure from without, and the execution of it absolute perfection. Even those who do not admire the Budget, or who are injured by it, admit the merit of the performance. It has raised Gladstone to a great political elevation, and, what is of far greater consequence than the measure itself, has given the country assurance of a man equal to great political necessities, and fit to lead parties and direct governments.[47]

During wartime, he insisted on raising taxes and not borrowing funds to pay for the war. The goal was to turn wealthy Britons against expensive wars. Britain entered the Crimean War in February 1854, and Gladstone introduced his budget on 6 March. He had to increase expenditure on the military and a vote of credit of £1,250,000 was taken to send a force of 25,000 to the front. The deficit for the year would be £2,840,000 (estimated revenue £56,680,000; estimated expenditure £59,420,000). Gladstone refused to borrow the money needed to rectify this deficit and instead increased income tax by half, from sevenpence to tenpence-halfpenny in the pound (from 2.92% to 4.38%). By May another £6,870,000 was needed for the war and Gladstone raised the income tax from tenpence halfpenny to fourteen pence in the pound to raise £3,250,000. Spirits, malt, and sugar were taxed to raise the rest of the money needed.[48] He proclaimed:

- The expenses of a war are the moral check which it has pleased the Almighty to impose upon the ambition and lust of conquest that are inherent in so many nations ... The necessity of meeting from year to year the expenditure which it entails is a salutary and wholesome check, making them feel what they are about, and making them measure the cost of the benefit upon which they may calculate.[49]

He served until 1855, a few weeks into Lord Palmerston's first premiership, and resigned along with the rest of the Peelites after a motion was passed to appoint a committee of inquiry into the conduct of the war.

Opposition (1855–1859)

[edit]

The Conservative Leader Lord Derby became Prime Minister in 1858, but Gladstone – who like the other Peelites was still nominally a Conservative – declined a position in his government, opting not to sacrifice his free-trade principles.

Between November 1858 and February 1859, Gladstone, on behalf of Lord Derby's government, was made Extraordinary Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands embarking via Vienna and Trieste on a twelve-week mission to the southern Adriatic entrusted with complex challenges that had arisen in connection with the future of the British protectorate of the United States of the Ionian Islands.[50]

In 1858, Gladstone took up the hobby of tree felling, mostly of oak trees, an exercise he continued with enthusiasm until he was 81 in 1891. Eventually, he became notorious for this activity, prompting Lord Randolph Churchill to observe:

For the purposes of recreation he has selected the felling of trees; and we may usefully remark that his amusements, like his politics, are essentially destructive. Every afternoon the whole world is invited to assist at the crashing fall of some beech or elm or oak. The forest laments in order that Mr Gladstone may perspire."[51]

Less noticed at the time was his practice of replacing the trees felled by planting new saplings.

Gladstone was a lifelong bibliophile.[52] In his lifetime, he read around 20,000 books, and eventually owned a library[53] of over 32,000.[54]

Chancellor of the Exchequer (1859–1866)

[edit]

In 1859, Lord Palmerston formed a new mixed government with Radicals included, and Gladstone again joined the government (with most of the other remaining Peelites) as Chancellor of the Exchequer, to become part of the new Liberal Party.

Gladstone inherited a deficit of nearly £5,000,000, with income tax now set at 5d (fivepence). Like Peel, Gladstone dismissed the idea of borrowing to cover the deficit. Gladstone argued that "In time of peace nothing but dire necessity should induce us to borrow".[55] Most of the money needed was acquired through raising the income tax to 9d. Usually, not more than two-thirds of a tax imposed could be collected in a financial year so Gladstone therefore imposed the extra four pence at a rate of 8d. during the first half of the year so that he could obtain the additional revenue in one year. Gladstone's dividing line set up in 1853 had been abolished in 1858 but Gladstone revived it, with lower incomes to pay 6½d. instead of 9d. For the first half of the year, the lower incomes paid 8d. and the higher incomes paid 13d. in income tax.[56]

On 12 September 1859 the Radical MP Richard Cobden visited Gladstone, who recorded it in his diary: "... further conv. with Mr. Cobden on Tariffs & relations with France. We are closely & warmly agreed".[57] Cobden was sent as Britain's representative to the negotiations with France's Michel Chevalier for a free trade treaty between the two countries. Gladstone wrote to Cobden:

... the great aim – the moral and political significance of the act, and its probable and desired fruit in binding the two countries together by interest and affection. Neither you nor I attach for the moment any superlative value to this Treaty for the sake of the extension of British trade. ... What I look to is the social good, the benefit to the relations of the two countries, and the effect on the peace of Europe.[58]

Gladstone's budget of 1860 was introduced on 10 February along with the Cobden–Chevalier Treaty between Britain and France that would reduce tariffs between the two countries.[59] This budget "marked the final adoption of the Free Trade principle, that taxation should be levied for Revenue purposes alone, and that every protective, differential, or discriminating duty ... should be dislodged".[60] At the beginning of 1859, there were 419 duties in existence. The 1860 budget reduced the number of duties to 48, with 15 duties constituting the majority of the revenue. To finance these reductions in indirect taxation, the income tax, instead of being abolished, was raised to 10d. for incomes above £150 and at 7d. for incomes above £100.[61]

In 1860 Gladstone intended to abolish the duty on paper – a controversial policy – because the duty traditionally inflated the cost of publishing and hindered the dissemination of radical working-class ideas. Although Palmerston supported the continuation of the duty, using it and income tax revenue to buy arms, a majority of his Cabinet supported Gladstone. The Bill to abolish duties on paper narrowly passed the Commons but was rejected by the House of Lords. No money bill had been rejected by the Lords for over 200 years, and a furore arose over this vote. The next year, Gladstone included the abolition of paper duty in a consolidated Finance Bill (the first ever) to force the Lords to accept it and accept it they did. The proposal in the Commons of one bill only per session for the national finances was a precedent uniformly followed from that date until 1910, and it has been ever since the rule.[62]

Gladstone steadily reduced Income tax over the course of his tenure as Chancellor. In 1861 the tax was reduced to ninepence (£0–0s–9d), in 1863 to sevenpence, in 1864 to fivepence and in 1865 to fourpence.[63] Gladstone believed that government was extravagant and wasteful with taxpayers' money and so sought to let money "fructify in the pockets of the people" by keeping taxation levels down through "peace and retrenchment". In 1859 he wrote to his brother, who was a member of the Financial Reform Association at Liverpool: "Economy is the first and great article (economy such as I understand it) in my financial creed. The controversy between direct and indirect taxation holds a minor, though important place".[64] He wrote to his wife on 14 January 1860: "I am certain, from experience, of the immense advantage of strict account-keeping in early life. It is just like learning the grammar then, which when once learned need not be referred to afterwards".[65][incomplete short citation] [a]

Because of his actions as Chancellor, Gladstone earned the reputation as the liberator of British trade and the working man's breakfast table, the man responsible for the emancipation of the popular press from "taxes upon knowledge" and for placing a duty on the succession of the estates of the rich.[67] Gladstone's popularity rested on his taxation policies which meant to his supporters balance, social equity and political justice.[68] The most significant expression of working-class opinion was at Northumberland in 1862 when Gladstone visited. George Holyoake recalled in 1865:

When Mr Gladstone visited the North, you well remember when word passed from the newspaper to the workman that it circulated through mines and mills, factories and workshops, and they came out to greet the only British minister who ever gave the English people a right because it was just they should have it ... and when he went down the Tyne, all the country heard how twenty miles of banks were lined with people who came to greet him. Men stood in the blaze of chimneys; the roofs of factories were crowded; colliers came up from the mines; women held up their children on the banks that it might be said in after life that they had seen the Chancellor of the People go by. The river was covered like the land. Every man who could ply an oar pulled up to give Mr Gladstone a cheer. When Lord Palmerston went to Bradford the streets were still, and working men imposed silence upon themselves. When Mr Gladstone appeared on the Tyne he heard cheer no other English minister ever heard ... the people were grateful to him, and rough pitmen who never approached a public man before, pressed round his carriage by thousands ... and thousands of arms were stretched out at once, to shake hands with Mr Gladstone as one of themselves.[69]

When Gladstone first joined Palmerston's government in 1859, he had opposed further electoral reform, but he changed his position during Palmerston's last premiership, and by 1865 he was firmly in favour of enfranchising the working classes in towns. The policy caused friction with Palmerston, who strongly opposed enfranchisement. At the beginning of each session, Gladstone would passionately urge the Cabinet to adopt new policies, while Palmerston would fixedly stare at a paper before him. At a lull in Gladstone's speech, Palmerston would smile, rap the table with his knuckles, and interject pointedly, "Now, my Lords and gentlemen, let us go to business".[70] Although he personally was not a Nonconformist, and rather disliked them in person, he formed a coalition with the Nonconformists that gave the Liberals a powerful base of support.[71]

American Civil War

[edit]Palmerston's government adopted a position of British neutrality throughout the war while declining to recognise the independence of the Confederacy. In October 1862 Gladstone made a speech in Newcastle in which he said that Jefferson Davis and the other Confederate leaders had "made a nation", and that the Confederacy seemed certain to succeed in asserting its independence from the North, and that the time might come when it would be the duty of the European powers to "offer friendly aid in compromising the quarrel."[72] The speech caused consternation on both sides of the Atlantic and led to speculation that Britain might be about to recognise the Confederacy.[73][74] Gladstone was accused of sympathising with the South, a charge he rejected.[75][76] Gladstone was forced to clarify in the press that his comments in Newcastle had not been intended to signal a change in Government policy, but to express his belief that the North's efforts to defeat the South would fail, due to the strength of Southern resistance.[73][77]

Electoral reform

[edit]In May 1864 Gladstone said that he saw no reason in principle why all mentally able men could not be enfranchised, but admitted that this would only come about once the working classes themselves showed more interest in the subject. Queen Victoria was not pleased with this statement, and an outraged Palmerston considered it a seditious incitement to agitation.[78]

Gladstone's support for electoral reform and disestablishment of the (Anglican) Church of Ireland won support from Nonconformists but alienated him from constituents in his Oxford University seat, and he lost it in the 1865 general election. A month later he stood as a candidate in South Lancashire, where he was elected third MP (South Lancashire at this time elected three MPs). Palmerston campaigned for Gladstone in Oxford because he believed that his constituents would keep him "partially muzzled"; many Oxford graduates were Anglican clergymen at that time. A victorious Gladstone told his new constituency, "At last, my friends, I am come among you; and I am come – to use an expression which has become very famous and is not likely to be forgotten – I am come 'unmuzzled'."[79]

On Palmerston's death in October, Earl Russell formed his second ministry.[80] Russell and Gladstone (now the senior Liberal in the House of Commons) attempted to pass a reform bill, which was defeated in the Commons because the "Adullamite" Whigs, led by Robert Lowe, refused to support it. The Conservatives then formed a ministry, in which after a long Parliamentary debate Disraeli passed the Second Reform Act of 1867; Gladstone's proposed bill had been totally outmanoeuvred; he stormed into the Chamber, but too late to see his arch-enemy pass the bill. Gladstone was furious; his animus commenced a long rivalry that would only end on Disraeli's death and Gladstone's encomium in the Commons in 1881.[81]

Leader of the Liberal Party, from 1867

[edit]Lord Russell retired in 1867 and Gladstone became leader of the Liberal Party.[8][82] In 1868 the Irish Church Resolutions were proposed as a measure to reunite the Liberal Party in government (on the issue of disestablishment of the Church of Ireland – this would be done during Gladstone's First Government in 1869 and meant that Irish Roman Catholics did not need to pay their tithes to the Anglican Church of Ireland).[83] When it was passed, Disraeli took the hint and called a General Election.

First premiership (1868–1874)

[edit]

In the next general election in 1868, the South Lancashire constituency had been broken up by the Second Reform Act into two: South East Lancashire and South West Lancashire. Gladstone stood for South West Lancashire and for Greenwich, it being quite common then for candidates to stand in two constituencies simultaneously.[86] To his great surprise he was defeated in South West Lancashire but, by winning in Greenwich, was able to remain in Parliament. He became prime minister for the first time and remained in office until 1874.[87] Evelyn Ashley recorded that he had been felling a tree at Hawarden when brought the news that he was about to be appointed prime minister. He broke off briefly to declare "My mission is to pacify Ireland" before resuming his exertions.[88]

In the 1860s and 1870s, Gladstonian Liberalism was characterised by a number of policies intended to improve individual liberty and loosen political and economic restraints. First was the minimisation of public expenditure on the premise that the economy and society were best helped by allowing people to spend as they saw fit. Secondly, his foreign policy aimed at promoting peace to help reduce expenditures and taxation and enhance trade. Thirdly, laws that prevented people from acting freely to improve themselves were reformed. When an unemployed miner (Daniel Jones) wrote to him to complain of his unemployment and low wages, Gladstone gave what H. C. G. Matthew has called "the classic mid-Victorian reply" on 20 October 1869:

The only means which have been placed in my power of 'raising the wages of colliers' has been by endeavouring to beat down all those restrictions upon trade which tend to reduce the price to be obtained for the product of their labour, & to lower as much as may be the taxes on the commodities which they may require for use or for consumption. Beyond this I look to the forethought not yet so widely diffused in this country as in Scotland, & in some foreign lands; & I need not remind you that in order to facilitate its exercise the Government have been empowered by Legislation to become through the Dept. of the P.O. the receivers & guardians of savings.[89]

Gladstone's first premiership instituted reforms in the British Army, civil service, and local government to cut restrictions on individual advancement. The Local Government Board Act 1871 put the supervision of the Poor Law under the Local Government Board (headed by G. J. Goschen) and Gladstone's "administration could claim spectacular success in enforcing a dramatic reduction in supposedly sentimental and unsystematic outdoor poor relief, and in making, in co-operation with the Charity Organization Society (1869), the most sustained attempt of the century to impose upon the working classes the Victorian values of providence, self-reliance, foresight, and self-discipline".[90] Gladstone was associated with the Charity Organization Society's first annual report in 1870.[91] Some leading Conservatives at this time were contemplating an alliance between the aristocracy and the working class against the capitalist class, an idea called the New Social Alliance.[92] At a speech at Blackheath on 28 October 1871, he warned his constituents against these social reformers:

... they are not your friends, but they are your enemies in fact, though not in intention, who teach you to look to the Legislature for the radical removal of the evils that afflict human life. ... It is the individual mind and conscience, it is the individual character, on which mainly human happiness or misery depends. (Cheers.) The social problems that confront us are many and formidable. Let the Government labour to its utmost, let the Legislature labour days and nights in your service; but, after the very best has been attained and achieved, the question whether the English father is to be the father of a happy family and the centre of a united home is a question which must depend mainly upon himself. (Cheers.) And those who ... promise to the dwellers in towns that every one of them shall have a house and garden in free air, with ample space; those who tell you that there shall be markets for selling at wholesale prices retail quantities – I won't say are impostors, because I have no doubt they are sincere; but I will say they are quacks (cheers); they are deluded and beguiled by a spurious philanthropy, and when they ought to give you substantial, even if they are humble and modest boons, they are endeavouring, perhaps without their own consciousness, to delude you with fanaticism, and offering to you a fruit which, when you attempt to taste it, will prove to be but ashes in your mouths. (Cheers.)[93]

Gladstone instituted the abolition of the sale of commissions in the army: he also instituted the Cardwell Reforms in 1869 that made peacetime flogging illegal. In 1870, his government passed the Irish Land Act and Forster's Education Act. In 1871 his government passed the Trade Union Act allowing trade unions to organise and operate legally for the first time (although picketing remained illegal). Gladstone later counted this reform as one of the most significant of the previous half-century, saying that before its passage the law had effectively "compelled the British workman to work...in chains."[94] In 1871, he instituted the Universities Tests Act. He secured passage of the Ballot Act for secret ballots, and the Licensing Act 1872. In foreign affairs, his over-riding aim was to promote peace and understanding, characterised by his settlement of the Alabama Claims in 1872 in favour of the Americans. During this time, his government gave the approval to launch the expedition of HMS Challenger at a time when public interest had turned away from scientific explorations.[95] His leadership also led to the passage of the Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1873 restructuring the courts to create the modern High Court and Court of Appeal.

Gladstone unexpectedly dissolved Parliament in January 1874 and called a general election.[b]

Gladstone's proposals went some way to meet working-class demands, such as the realisation of the free breakfast table through repealing duties on tea and sugar, and reform of local taxation which was increasing for the poorer ratepayers.[97] According to the working-class financial reformer Thomas Briggs, writing in the trade unionist newspaper The Bee-Hive, the manifesto relied on "a much higher authority than Mr. Gladstone...viz., the late Richard Cobden".[98] The dissolution itself was reported in The Times on 24 January. On 30 January, the names of the first fourteen MPs for uncontested seats were published. By 9 February a Conservative victory was apparent. In contrast to 1868 and 1880 when the Liberal campaign lasted several months, only three weeks separated the news of the dissolution and the election. The working-class newspapers were so taken by surprise they had little time to express an opinion on Gladstone's manifesto before the election was over.[99] Unlike the efforts of the Conservatives, the organisation of the Liberal Party had declined since 1868 and they had also failed to retain Liberal voters on the electoral register. George Howell wrote to Gladstone on 12 February: "There is one lesson to be learned from this Election, that is Organization. ... We have lost not by a change of sentiment so much as by want of organised power".[100] The Liberals received a majority of the vote in each of the constituent countries of the United Kingdom and 189,000 more votes nationally than the Conservatives. However, they obtained a minority of seats in the House of Commons.[101]

Opposition (1874–1880)

[edit]

In the wake of Benjamin Disraeli's victory, Gladstone retired from the leadership of the Liberal party, although he retained his seat in the House.

Anti-Catholicism

[edit]Gladstone had a complex ambivalence about Catholicism. He was attracted by its international success in majestic traditions. More important, he was strongly opposed to the authoritarianism of its pope and bishops, its profound public opposition to liberalism, and its supposed refusal to distinguish between secular allegiance on the one hand and spiritual obedience on the other.[102][103]

In November 1874, he published the pamphlet The Vatican Decrees in their Bearing on Civil Allegiance, directed at the First Vatican Council's dogmatising Papal Infallibility in 1870, which had outraged him.[104] Gladstone claimed that this decree had placed British Catholics in a dilemma over conflicts of loyalty to the Crown. He urged them to reject papal infallibility as they had opposed the Spanish Armada of 1588. The pamphlet sold 150,000 copies by the end of 1874. Cardinal Manning denied that the council had changed the relation of Catholics to their civil governments, and Archbishop James Roosevelt Bayley, in a letter which was obtained by the New York Herald and published without Bayley's express permission, called Gladstone's declaration "a shameful calumny" and attributed his "monomania" to the "political hari-kari" he had committed by dissolving Parliament, accusing him of "putting on 'the cap and bells' and attempting to play the part of Lord George Gordon" in order to restore his political fortunes.[105][106] John Henry Newman wrote the Letter to the Duke of Norfolk in reply to Gladstone's charges that Catholics have "no mental freedom" and cannot be good citizens.

A second pamphlet followed in Feb 1875, a defence of the earlier pamphlet and a reply to his critics, entitled Vaticanism: an Answer to Reproofs and Replies.[107] He described the Catholic Church as "an Asian monarchy: nothing but one giddy height of despotism, and one dead level of religious subservience". He further claimed that the Pope wanted to destroy the rule of law and replace it with arbitrary tyranny, and then to hide these "crimes against liberty beneath a suffocating cloud of incense".[108]

Opposition to socialism

[edit]Gladstone was opposed to socialism after 1842 when he heard a socialist lecturer.[109] Lord Kilbracken, one of Gladstone's secretaries, commented:

The Liberal doctrines of that time, with their violent anti-socialist spirit and their strong insistence on the gospel of thrift, self-help, settlement of wages by the higgling of the market, and non-interference by the State.... I think that Mr. Gladstone was the strongest anti-socialist that I have ever known....It is quite true, as has been often said, that "we are all socialists up to a certain point"; but Mr. Gladstone fixed that point lower, and was more vehement against those who went above it, than any other politician or official of my acquaintance. I remember his speaking indignantly to me of the budget of 1874 as "That socialistic budget of Northcote's," merely because of the special relief which it gave to the poorer class of income-tax payers. His strong belief in Free Trade was only one of the results of his deep-rooted conviction that the Government's interference with the free action of the individual, whether by taxation or otherwise, should be kept at an irreducible minimum. It is, indeed, not too much to say that his conception of Liberalism was the negation of Socialism.[110]

Bulgarian Horrors

[edit]A pamphlet Gladstone published on 6 September 1876, Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East,[111][112][113] attacked the Disraeli government for its indifference to the Ottoman Empire's violent repression of the Bulgarian April uprising. Gladstone made clear his hostility focused on the Turkish people, rather than on the Muslim religion. The Turks he said:

were, upon the whole, from the black day when they first entered Europe, the one great anti-human specimen of humanity. Wherever they went, a broad line of blood marked the track behind them; and as far as their dominion reached, civilisation disappeared from view. They represented everywhere government by force, as opposed to government by law. For the guide of this life they had a relentless fatalism: for its reward hereafter, a sensual paradise.[114]

The historian Geoffrey Alderman has described Gladstone as "unleashing the full fury of his oratorical powers against Jews and Jewish influence" during the Bulgarian Crisis (1885–88), telling a journalist in 1876 that: "I deeply deplore the manner in which, what I may call Judaic sympathies, beyond as well as within the circle of professed Judaism, are now acting on the question of the East". Gladstone similarly refused to speak out against the persecution of Romanian Jews in the 1870s and Russian Jews in the early 1880s.< In response, the Jewish Chronicle attacked Gladstone in 1888, arguing that "Are we, because there was once a Liberal Party, to bow down and worship Gladstone – the great Minister who was too Christian in his charity, too Russian in his proclivities, to raise voice or finger" to defend Russian Jews...[115]

During the 1879 election campaign, called the Midlothian campaign, he rousingly denounced Disraeli's foreign policies during the ongoing Second Anglo-Afghan War in Afghanistan (see Great Game). He saw the war as "great dishonour" and also criticised British conduct in the Zulu War. Gladstone also (on 29 November) condemned what he saw as the Conservative government's profligate spending:

...the Chancellor of the Exchequer shall boldly uphold economy in detail; and it is the mark ... of ... a chicken-hearted Chancellor of the Exchequer, when he shrinks from upholding economy in detail, when, because it is a question of only £2,000 or £3,000, he says that is no matter. He is ridiculed, no doubt, for what is called saving candle-ends and cheese-parings. No Chancellor of the Exchequer is worth his salt who is not ready to save what are meant by candle-ends and cheese-parings in the cause of his country. No Chancellor of the Exchequer is worth his salt who makes his own popularity either his first consideration, or any consideration at all, in administrating the public purse. You would not like to have a housekeeper or steward who made her or his popularity with the tradesmen the measure of the payments that were to be delivered to them. In my opinion the Chancellor of the Exchequer is the trusted and confidential steward of the public. He is under a sacred obligation with regard to all that he consents to spend.... I am bound to say hardly ever in the six years that Sir Stafford Northcote has been in office have I heard him speak a resolute word on behalf of economy.[116]

Second premiership (1880–1885)

[edit]

In 1880, the Liberals won again and the Liberal leaders, Lord Hartington (leader in the House of Commons) and Lord Granville, retired in Gladstone's favour. Gladstone won his constituency election in Midlothian and also in Leeds, where he had also been adopted as a candidate. As he could lawfully only serve as MP for one constituency, Leeds was passed to his son Herbert. One of his other sons, Henry, was also elected as an MP. Queen Victoria asked Lord Hartington to form a ministry, but he persuaded her to send for Gladstone. Gladstone's second administration – both as Prime Minister and again as Chancellor of the Exchequer until 1882 – lasted from June 1880 to June 1885. He originally intended to retire at the end of 1882, the 50th anniversary of his entry into politics, but did not do so.[117]

Foreign policy

[edit]Historians have debated the wisdom of Gladstone's foreign policy during his second ministry.[118][119] Paul Hayes says it "provides one of the most intriguing and perplexing tales of muddle and incompetence in foreign affairs, unsurpassed in modern political history until the days of Grey and, later, Neville Chamberlain."[120] Gladstone opposed himself to the "colonial lobby" pushing for the scramble for Africa. His term saw the end of the Second Anglo-Afghan War, the First Boer War, and the war against the Mahdi in Sudan.

On 11 July 1882, Gladstone ordered the bombardment of Alexandria, starting the short, Anglo-Egyptian War of 1882. The British won decisively, and although they repeatedly promised to depart in a few years, the actual result was British control of Egypt for four decades, largely ignoring Ottoman nominal ownership. France was seriously unhappy, having lost control of the canal that it built and financed and had dreamed of for decades. Gladstone's role in the decision to invade was described as relatively hands-off, and the ultimate responsibility was borne by certain members of his cabinet such as Lord Hartington, Secretary of State for India; Thomas Baring, 1st Earl of Northbrook, First Lord of the Admiralty; Hugh Childers, Secretary of State for War; and Granville Leveson-Gower, 2nd Earl Granville, the Foreign Secretary.[121]

Historian A. J. P. Taylor says that the seizure of Egypt "was a great event; indeed, the only real event in international relations between the Battle of Sedan and the defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese war."[122] Taylor emphasizes long-term impact:

The British occupation of Egypt altered the balance of power. It not only gave the British security for their route to India, it made them masters of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East. It made it unnecessary for them to stand on the front line against Russia at the Straits....And thus prepared the way for the Franco-Russian Alliance ten years later.[123]

Gladstone and the Liberals had a reputation for strong opposition to imperialism, so historians have long debated the explanation for this reversal of policy. The most influential was a study by John Robinson and Ronald Gallagher, Africa and the Victorians (1961), which focused on The Imperialism of Free Trade and was promoted by the Cambridge School of historiography. They argue there was no long-term Liberal plan in support of imperialism. Instead, they saw the urgent necessity to act to protect the Suez Canal in the face of what appeared to be a radical collapse of law and order, and a nationalist revolt focused on expelling the Europeans, regardless of the damage it would do to international trade and the British Empire. Gladstone's decision came against strained relations with France and manoeuvring by "men on the spot" in Egypt. Critics such as Cain and Hopkins have stressed the need to protect large sums invested by British financiers and Egyptian bonds while downplaying the risk to the viability of the Suez Canal. Unlike the Marxists, they stress "gentlemanly" financial and commercial interests, not the industrial capitalism that Marxists believe was always central.[124] More recently, specialists on Egypt have been interested primarily in the internal dynamics among Egyptians that produce the failed Urabi Revolt.[125][126]

Ireland

[edit]In 1881 he established the Irish Coercion Act, which permitted the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland to detain people for as "long as was thought necessary", as there was rural disturbance in Ireland between landlords and tenants as Cavendish, the Irish Secretary, had been assassinated by Irish rebels in Dublin.[127] He also passed the Second Land Act (the First, in 1870, had entitled Irish tenants, if evicted, to compensation for improvements which they had made on their property, but had little effect) which gave Irish tenants the "3Fs" – fair rent, fixity of tenure and free sale.[128] He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1881.[129]

Franchise

[edit]

Gladstone extended the vote to agricultural labourers and others in the 1884 Reform Act, which gave the counties the same franchise as the boroughs – adult male householders and £10 lodgers – and added six million to the total number of people who could vote in parliamentary elections.[130] Parliamentary reform continued with the Redistribution of Seats Act 1885.[131]

Gladstone was increasingly uneasy about the direction in which British politics was moving. In a letter to Lord Acton on 11 February 1885, Gladstone criticised Tory Democracy as "demagogism" that "put down pacific, law-respecting, economic elements that ennobled the old Conservatism" but "still, in secret, as obstinately attached as ever to the evil principle of class interests". He found contemporary Liberalism better, "but far from being good". Gladstone claimed that this Liberalism's "pet idea is what they call construction, – that is to say, taking into the hands of the state the business of the individual man". Both Tory Democracy and this new Liberalism, Gladstone wrote, had done "much to estrange me, and had for many, many years".[132]

Failure

[edit]Historian Sneh Mahajan has concluded that "Gladstone's second ministry remained barren of any achievement in the domestic sphere".[133] His downfall came in Africa, where he delayed the mission to rescue General Gordon's force which had been under siege in Khartoum for 10 months. It arrived in January 1885 two days after a massacre killed approximately 7,000 British and Egyptian soldiers and 4,000 civilians. The disaster proved a major blow to Gladstone's popularity. Queen Victoria sent him a telegram of rebuke which found its way into the press. Critics said Gladstone had neglected military affairs and had not acted promptly enough to save the besieged Gordon. Critics inverted his acronym, "G.O.M." (for "Grand Old Man"), to "M.O.G." (for "Murderer of Gordon"). He resigned as prime minister in June 1885 and declined Queen Victoria's offer of an earldom.[134]

Third premiership (1886)

[edit]

The Hawarden Kite was a December 1885 press release by Gladstone's son and aide Herbert Gladstone announcing that he had become convinced that Ireland needed a separate parliament.[135][136] The bombshell announcement resulted in the fall of Lord Salisbury's Conservative government. Irish Nationalists, led by Charles Parnell's Irish Parliamentary Party, held the balance of power in Parliament. Gladstone's conversion to Home Rule convinced them to switch away from the Conservatives and support the Liberals using the 86 seats in Parliament they controlled. The main purpose of this administration was to deliver Ireland a reform that would give it a devolved assembly, similar to those which would eventually be put in place in Scotland and Wales in 1999. In 1886 Gladstone's party allied with Irish Nationalists to defeat Lord Salisbury's government. Gladstone regained his position as prime minister and combined the office with that of Lord Privy Seal. During this administration, he first introduced his Home Rule Bill for Ireland. The issue split the Liberal Party (a breakaway group went on to create the Liberal Unionist party) and the bill was thrown out on the second reading, ending his government after only a few months and inaugurating another headed by Lord Salisbury.

Gladstone, says his biographer, "totally rejected the widespread English view that the Irish had no taste for justice, common sense, moderation or national prosperity and looked only to perpetual strife and dissension".[137] The problem for Gladstone was that his rural English supporters would not support Home Rule for Ireland. A large faction of Liberals, led by Joseph Chamberlain, formed a Unionist faction that supported the Conservative party. Whenever the Liberals were out of power, Home Rule proposals languished.

Opposition (1886–1892)

[edit]

Gladstone supported the London dockers in their strike of 1889. After their victory he gave a speech at Hawarden on 23 September in which he said: "In the common interests of humanity, this remarkable strike and the results of this strike, which have tended somewhat to strengthen the condition of labour in the face of capital, is the record of what we ought to regard as satisfactory, as a real social advance [that] tends to a fair principle of division of the fruits of industry".[138] This speech has been described by Eugenio Biagini as having "no parallel in the rest of Europe except in the rhetoric of the toughest socialist leaders".[139] Visitors at Hawarden in October were "shocked...by some rather wild language on the Dock labourers question".[138] Gladstone was impressed with workers unconnected with the dockers' dispute who "intended to make common cause" in the interests of justice.

On 23 October at Southport, Gladstone delivered a speech where he said that the right to combination, which in London was "innocent and lawful, in Ireland would be penal and...punished by imprisonment with hard labour". Gladstone believed that the right to combination used by British workers was in jeopardy when it could be denied to Irish workers.[140] In October 1890 Gladstone at Midlothian claimed that competition between capital and labour, "where it has gone to sharp issues, where there have been strikes on one side and lock-outs on the other, I believe that in the main and as a general rule, the labouring man has been in the right".[141]

On 11 December 1891 Gladstone said that: "It is a lamentable fact if, in the midst of our civilisation, and at the close of the nineteenth century, the workhouse is all that can be offered to the industrious labourer at the end of a long and honourable life. I do not enter into the question now in detail. I do not say it is an easy one; I do not say that it will be solved in a moment; but I do say this, that until society is able to offer to the industrious labourer at the end of a long and blameless life something better than the workhouse, society will not have discharged its duties to its poorer members".[142] On 24 March 1892 Gladstone said that the Liberals had:

...come generally...to the conclusion that there is something painful in the condition of the rural labourer in this great respect, that it is hard even for the industrious and sober man, under ordinary conditions, to secure a provision for his own old age. Very large propositions, involving, some of them, very novel and very wide principles, have been submitted to the public, for the purpose of securing such a provision by means independent of the labourer himself....our duty [is] to develop in the first instance, every means that we may possibly devise whereby, if possible, the labourer may be able to make this provision for himself, or to approximate towards making such provision far more efficaciously and much more closely than he can now do.[143][144]

Gladstone wrote on 16 July 1892 in autobiographica that "In 1834 the Government...did themselves high honour by the new Poor Law Act, which rescued the English peasantry from the total loss of their independence".[145] There were many who disagreed with him.

Gladstone wrote to Herbert Spencer, who contributed the introduction to a collection of anti-socialist essays (A Plea for Liberty, 1891), that "I ask to make reserves, and of one passage, which will be easily guessed, I am unable even to perceive the relevancy. But speaking generally, I have read this masterly argument with warm admiration and with the earnest hope that it may attract all the attention which it so well deserves".[146] The passage Gladstone alluded to was one where Spencer had spoken of "the behaviour of the so-called Liberal party".[146]

Fourth premiership (1892–1894)

[edit]

The general election of 1892 resulted in a minority Liberal government with Gladstone as prime minister. The electoral address had promised Irish Home Rule and the disestablishment of the Scottish and Welsh Churches.[147] In February 1893 he introduced the Second Home Rule Bill, which was passed in the Commons at the second reading on 21 April by 43 votes and the third reading on 1 September by 34 votes. The House of Lords defeated the bill by voting against it by 419 votes to 41 on 8 September.

The Elementary Education (Blind and Deaf Children) Act, passed in 1893, required local authorities to provide separate education for blind and deaf children.[148]

Conservative MP Colonel Howard Vincent questioned Gladstone in the Commons on what his government would do about unemployment on 1 September 1893. Gladstone replied:

I cannot help regretting that the honourable and gallant Gentleman has felt it his duty to put the question. It is put under circumstances that naturally belong to one of those fluctuations in the condition of trade which, however unfortunate and lamentable they may be, recur from time to time. Undoubtedly I think that questions of this kind, whatever be the intention of the questioner, have a tendency to produce in the minds of people or to suggest to the people, that these fluctuations can be corrected by the action of the Executive Government. Anything that contributes to such an impression inflicts an injury upon the labouring population.[149][150]

In December 1893, an Opposition motion proposed by Lord George Hamilton called for an expansion of the Royal Navy. Gladstone opposed increasing public expenditure on the naval estimates, in the tradition of free trade liberalism of his earlier political career as Chancellor. All his Cabinet colleagues believed in some expansion of the navy. He declared in the Commons on 19 December that naval rearmament would commit the government to expenditure over a number of years and would subvert "the principle of annual account, annual proposition, annual approval by the House of Commons, which...is the only way of maintaining regularity, and that regularity is the only talisman which will secure Parliamentary control".[151] In January 1894, Gladstone wrote that he would not "break to pieces the continuous action of my political life, nor trample on the tradition received from every colleague who has ever been my teacher" by supporting naval rearmament.[152] Gladstone also opposed Chancellor Sir William Harcourt's proposal to implement a graduated death duty. In a fragment of autobiography dated 25 July 1894, Gladstone denounced the tax as

...by far the most Radical measure of my lifetime. I do not object to the principle of graduated taxation: for the just principle of the ability to pay is not determined simply by the amount of income.... But, so far as I understand the present measure of finance from the partial reports I have received, I find it too violent. It involves a great departure from the methods of political action established in this country, where reforms, and especially financial reforms, have always been considerate and even tender.... I do not yet see the ground on which it can be justly held that any one description of property should be more heavily burdened than others unless moral and social grounds can be shown first: but in this case, the reasons drawn from those sources seem rather to verge in the opposite direction, for real property has more of presumptive connection with the discharge of duty than that which is ranked as personal...the aspect of the measure is not satisfactory to a man of my traditions (and these traditions lie near the roots of my being).... For the sudden introduction of such change, there is I think no precedent in the history of this country. And the severity of the blow is greatly aggravated in moral effect by the fact that it is dealt only to a handful of individuals.[153]

Gladstone had his last audience with Queen Victoria on 28 February 1894 and chaired his last Cabinet on 1 March – the last of 556 he had chaired. On that day he gave his last speech to the House of Commons, saying that the government would withdraw opposition to the Lords' amendments to the Local Government Bill "under protest" and that it was "a controversy which, when once raised, must go forward to an issue".[154] He resigned from the premiership on 2 March. The Queen did not ask Gladstone who should succeed him but sent for Lord Rosebery (Gladstone would have advised on Lord Spencer).[155] He retained his seat in the House of Commons until 1895. He was not offered a peerage, having earlier declined an earldom.

Gladstone is both the oldest person to form a government – aged 82 at his appointment – and the oldest person to occupy the Premiership – being 84 at his resignation.[156]

Final years (1894–1898)

[edit]

In 1895, at the age of 85, Gladstone bequeathed £40,000 (equivalent to approximately £5.84 million today)[157] and much of his 32,000 volume library to found St Deiniol's Library in Hawarden, Wales.[158] It had begun with just 5,000 items at his father's home Fasque, which were transferred to Hawarden for research in 1851.

On 8 January 1896, in conversation with L. A. Tollemache, Gladstone explained that: "I am not so much afraid of Democracy or of Science as of the love of money. This seems to me to be a growing evil. Also, there is a danger from the growth of that dreadful military spirit".[159] On 13 January, Gladstone claimed he had strong Conservative instincts and that "In all matters of custom and tradition, even the Tories look upon me as the chief Conservative that is".[160] On 15 January Gladstone wrote to James Bryce, describing himself as "a dead man, one fundamentally a Peel–Cobden man".[161] In 1896, in his last noteworthy speech, he denounced Armenian massacres by Ottomans in a talk delivered at Liverpool. On 2 January 1897, Gladstone wrote to Francis Hirst on being unable to draft a preface to a book on liberalism: "I venture on assuring you that I regard the design formed by you and your friends with sincere interest, and in particular wish well to all the efforts you may make on behalf of individual freedom and independence as opposed to what is termed Collectivism".[162][163]

In the early months of 1897, Gladstone and his wife stayed in Cannes. Gladstone met Queen Victoria, and she shook hands with him for (to his recollection) the first time in the 50 years he had known her.[164] One of the Gladstones' neighbours observed that "He and his devoted wife never missed the morning service on Sunday ... One Sunday, returning from the altar rail, the old, partially blind man stumbled at the chancel step. One of the clergy sprang involuntarily to his assistance but retreated with haste, so withering was the fire which flashed from those failing eyes."[165] The Gladstones returned to Hawarden Castle at the end of March and he received the Colonial Premiers in their visit for the Queen's Jubilee. At a dinner in November with Edward Hamilton, his former private secretary, Hamilton noted that "What is now uppermost in his mind is what he calls the spirit of jingoism under the name of Imperialism which is now so prevalent". Gladstone riposted "It was enough to make Peel and Cobden turn in their graves".[166]

On the advice of his doctor Samuel Habershon in the aftermath of an attack of facial neuralgia, Gladstone stayed at Cannes from the end of November 1897 to mid-February 1898. He gave an interview for The Daily Telegraph.[167] Gladstone then travelled to Bournemouth, where a swelling on his palate was diagnosed as cancer by the leading cancer surgeon Sir Thomas Smith on 18 March. On 22 March, he retired to Hawarden Castle. Despite being in pain he received visitors and quoted hymns, especially Cardinal Newman's "Praise to the Holiest in the Height".

His last public statement was dictated to his daughter Helen in reply to receiving the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford's "sorrow and affection": "There is no expression of Christian sympathy that I value more than that of the ancient University of Oxford, the God-fearing and God-sustaining University of Oxford. I served her perhaps mistakenly, but to the best of my ability. My most earnest prayers are hers to the uttermost and to the last".[168] He left the house for the last time on 9 April. After 18 April he did not come down to the ground floor but still came out of bed to lie on the sofa. The Bishop of St Andrews, Dunkeld and Dunblane George Wilkinson recorded when he ministered to him along with Stephen Gladstone:

Shall I ever forget the last Friday in Passion Week, when I gave him the last Holy Communion that I was allowed to administer to him? It was early in the morning. He was obliged to be in bed, and he was ordered to remain there, but the time had come for the confession of sin and the receiving of absolution. Out of his bed he came. Alone he knelt in the presence of his God till the absolution has been spoken, and the sacred elements received.[169]

Gladstone died on 19 May 1898 at Hawarden Castle aged 88. He had been cared for by his daughter Helen who had resigned from her job to care for her father and mother.[170] The cause of death is officially recorded as "Syncope, Senility". "Syncope" meant failure of the heart and "senility" in the 19th century was an infirmity of advanced old age, rather than a loss of mental faculties.[171] The House of Commons adjourned on the afternoon of Gladstone's death, with A. J. Balfour giving notice for an Address to the Queen praying for a public funeral and a public memorial in Westminster Abbey. The day after, both Houses of Parliament approved the Address and Herbert Gladstone accepted a public funeral on behalf of the Gladstone family.[172] His coffin was transported on the London Underground before his state funeral at Westminster Abbey, at which the Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII) and the Duke of York (the future King George V) acted as pallbearers.[173] His wife, Catherine Gladstone (née Glynne), died two years later on 14 June 1900 and was buried next to him.

Religion

[edit]Gladstone's intensely religious mother was an evangelical of Scottish Episcopal origins,[174] and his father joined the Church of England, having been a Presbyterian when he first settled in Liverpool. As a boy, William was baptised into the Church of England. He rejected a call to enter the ministry, and on this his conscience always tormented him. In compensation, he aligned his politics with the evangelical faith in which he fervently believed.[175] In 1838 Gladstone nearly ruined his career when he tried to force a religious mission upon the Conservative Party. His book The State in its Relations with the Church argued that England had neglected its great duty to the Church of England. He announced that since that church possessed a monopoly of religious truth, nonconformists and Roman Catholics ought to be excluded from all government positions. The historian Thomas Babington Macaulay and other critics ridiculed his arguments and refuted them. Sir Robert Peel, Gladstone's chief, was outraged because this would upset the delicate political issue of Catholic Emancipation and anger the Nonconformists. Since Peel greatly admired his protégé, he redirected his focus from theology to finance.[176]

Gladstone altered his approach to religious problems, which always held first place in his mind. Before entering Parliament he had already substituted a high church Anglican attitude, with its dependence on authority and tradition, for the evangelical outlook of his boyhood, with its reliance upon the direct inspiration of the Bible. In middle life, he decided that the individual conscience would have to replace authority as the inner citadel of the Church. That view of the individual conscience affected his political outlook and changed him gradually from a Conservative into a Liberal.[177]

Attitude towards slavery

[edit]Initially a disciple of High Toryism, Gladstone's maiden speech as a young Tory was a defence of the rights of West Indian sugar plantation magnates – slave-owners – among whom his father was prominent. He immediately came under attack from anti-slavery elements. He also surprised the duke by urging the need to increase pay for unskilled factory workers.[178]

Gladstone's early attitude towards slavery was highly shaped by his father, Sir John Gladstone, one of the largest slave owners in the British Empire. Gladstone wanted gradual rather than immediate emancipation, and proposed that slaves should serve a period of apprenticeship after being freed.[179] They also opposed the international slave trade (which lowered the value of the slaves the father already owned).[180][181] The anti-slavery movement demanded the immediate abolition of slavery. Gladstone opposed this and said in 1832 that emancipation should come after moral emancipation through the adoption of education and the inculcation of "honest and industrious habits" among the slaves. Then "with the utmost speed that prudence will permit, we shall arrive at that exceedingly desired consummation, the utter extinction of slavery."[182] In 1831, when the Oxford Union considered a motion in favour of the immediate emancipation of the slaves in the West Indies, Gladstone moved an amendment in favour of gradual manumission along with better protection for the personal and civil rights of the slaves and better provision for their Christian education.[183] His early Parliamentary speeches followed a similar line: in June 1833, Gladstone concluded his speech on the 'slavery question' by declaring that though he had dwelt on "the dark side" of the issue, he looked forward to "a safe and gradual emancipation".[184]

In 1834, when slavery was abolished across the British Empire, the owners were paid full value for the slaves. Gladstone helped his father obtain £106,769 (equivalent to £12,960,000 in 2023) in official reimbursement by the government for the 2,508 slaves he owned across nine plantations in the Caribbean.[185]

In later years Gladstone's attitude towards slavery became more critical as his father's influence over his politics diminished. In 1844 Gladstone broke with his father when, as President of the Board of Trade, he advanced proposals to halve duties on foreign sugar not produced by slave labour, in order to "secure the effectual exclusion of slave-grown sugar" and to encourage Brazil and Spain to end slavery.[186] Sir John Gladstone, who opposed any reduction in duties on foreign sugar, wrote a letter to The Times criticizing the measure.[187] Looking back late in life, Gladstone named the abolition of slavery as one of ten great achievements of the previous sixty years where the masses had been right and the upper classes had been wrong.[94]

Shortly after the outbreak of the American Civil War Gladstone wrote to his friend the Duchess of Sutherland that "the principle announced by the vice-president of the South...which asserts the superiority of the white man, and therewith founds on it his right to hold the black in slavery, I think that principle detestable, and I am wholly with the opponents of it" but that he felt that the North was wrong to try to restore the Union by military force, which he believed would end in failure.[76]

In a memorandum to the Cabinet later that month Gladstone wrote that, although he believed the Confederacy would probably win the war, it was "seriously tainted by its connection with slavery" and argued that the European powers should use their influence on the South to effect the "mitigation or removal of slavery."[188]

Marriage and family

[edit]

Gladstone's early attempts to find a wife proved unsuccessful; he was rejected in 1835 by Caroline Eliza Farquhar (daughter of Sir Thomas Harvie Farquhar, 2nd Baronet) and again in 1837 by Lady Frances Harriet Douglas (daughter of George Douglas, 17th Earl of Morton).[189]

The following year, having met Catherine Glynne in 1834 at the London home of Old Etonian friend and then fellow-Conservative MP James Milnes Gaskell,[190] he married her on 25 July 1839 – a joint wedding shared with Catherine's sister Mary Glynne and betrothed George Lyttelton. Catherine and William remained married until Gladstone's death 59 years later and had eight children together:

- William Henry Gladstone MP (1840–1891); married Hon. Gertrude Stuart (daughter of Charles Stuart, 12th Lord Blantyre) in 1875. They had three children.

- Agnes Gladstone (1842–1931); she married Very Rev. Edward Wickham in 1873. They had four children.[citation needed]

- The Rev. Stephen Edward Gladstone (1844–1920); married Annie Wilson in 1885. They had five children: their eldest son Albert, inherited the Gladstone baronetcy in 1945.

- Catherine Jessy Gladstone (1845–1850); died aged 5 on 9 April 1850 from meningitis