Edward Burne-Jones

Edward Burne-Jones | |

|---|---|

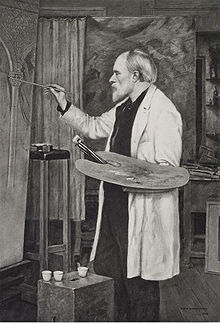

Photogravure of a portrait of Edward Burne-Jones by his son Philip Burne-Jones, 1898 | |

| Born | Edward Coley Burne Jones 28 August 1833 Birmingham, England |

| Died | 17 June 1898 (aged 64) London, England |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | |

| Spouse | |

| Partner | Maria Zambaco (1866–1869) |

| Relatives |

|

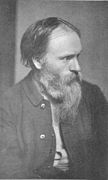

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, 1st Baronet, ARA (/bɜːrnˈdʒoʊnz/;[1] 28 August 1833 – 17 June 1898) was an English painter and designer associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood's style and subject matter.[2]

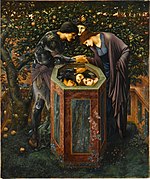

Burne-Jones worked with William Morris as a founding partner in Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co in the design of decorative arts.[3] His early paintings show the influence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, but by 1870 he had developed his own style. In 1877, he exhibited eight oil paintings at the Grosvenor Gallery (a new rival to the Royal Academy). These included The Beguiling of Merlin. The timing was right and he was taken up as a herald and star of the new Aesthetic Movement.

In the studio of Morris and Co. Burne-Jones worked as a designer of a wide range of crafts including ceramic tiles, jewellery, tapestries, and mosaics. Among his most significant and lasting designs are those for stained glass windows the production of which was a revived craft during the 19th century. His designs are still to be found in churches across the UK, with examples in the US and Australia.

Early life

[edit]

Born Edward Coley Burne Jones (the hyphenation of his last names was introduced later) was born in Birmingham, the son of a Welshman, Edward Richard Jones, a frame-maker at Bennetts Hill, where a blue plaque commemorates the painter's childhood. A pub on the site of the house is called the Briar Rose in honour of Burne-Jones' work.[3] His mother Elizabeth Jones (née Coley) died within six days of his birth, and Edward was raised by his father, and the family housekeeper, Ann Sampson, an obsessively affectionate but humourless, and unintellectual local girl.[4][5] He attended Birmingham's King Edward VI grammar school in 1844 and the Birmingham School of Art from 1848 to 1852, before studying theology at Exeter College, Oxford.[6] At Oxford, he became a friend of William Morris as a consequence of a mutual interest in poetry. The two Exeter undergraduates, together with a group of Jones' friends from Birmingham known as the Birmingham Set,[7] formed a society, which they called "The Brotherhood". The members of the brotherhood read the works of John Ruskin and Tennyson, visited churches, and idealised aspects of the aesthetics and social structure of the Middle Ages.[3] At this time, Burne-Jones discovered Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur which would become a substantial influential in his life. At that time, neither Burne-Jones nor Morris knew Dante Gabriel Rossetti personally, but both were much influenced by his works, and later met him by recruiting him as a contributor to their Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, founded by Morris in 1856 to promote the Brotherhood’s ideas.[8][9]

Burne-Jones had intended to become a church minister, but under Rossetti's influence both he and Morris decided to become artists, and Burne-Jones left college before taking a degree to pursue a career in art. In February 1857, Rossetti wrote to William Bell Scott:

Two young men, projectors of the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, have recently come up to town from Oxford, and are now very intimate friends of mine. Their names are Morris and Jones. They have turned artists instead of taking up any other career to which the university generally leads, and both are men of real genius. Jones's designs are marvels of finish and imaginative detail, unequalled by anything unless perhaps Albert Dürer's finest works.[8]

Marriage and family

[edit]

In 1856 Burne-Jones became engaged to Georgiana "Georgie" MacDonald (1840–1920), one of the MacDonald sisters. She was training to be a painter, and was the sister of Burne-Jones's old school friend. The couple married on 9 June 1860, after which she made her own work in woodcuts, and became a close friend of George Eliot. (Another MacDonald sister married the artist Sir Edward Poynter, a further sister married the ironmaster Alfred Baldwin and was the mother of the Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, and yet another sister was the mother of Rudyard Kipling. Kipling and Baldwin were thus Burne-Jones's nephews by marriage).

Georgiana gave birth to a son, Philip, in 1861. In the winter of 1864, she became gravely ill with scarlet fever and gave birth to a second son, Christopher, who died soon thereafter. The family then moved to 41 Kensington Square, and their daughter Margaret was born there in 1866.[10]

In 1867 Burne-Jones and his family settled at the Grange, an 18th-century house set in a garden in North End, Fulham, London. For the 1870s Burne-Jones did not exhibit, following a number of bitterly hostile attacks in the press, and a passionate affair (described as the "emotional climax of his life")[11] with his Greek model Maria Zambaco, which ended with her trying to commit suicide by throwing herself into Regent's Canal.[11][12]

During these difficult years, Georgiana developed a friendship with Morris, whose wife Jane had fallen in love with Rossetti. Morris and Georgie may have been in love, but if he asked her to leave her husband, she refused. In the end, the Burne-Joneses remained together, as did the Morrises, but Morris and Georgiana were close for the rest of their lives.[13]

In 1880, the Burne-Joneses bought Prospect House in Rottingdean, near Brighton in Sussex, as their holiday home and soon after, the next door Aubrey Cottage to create North End House, reflecting the fact that their Fulham home was in North End Road. (Years later, in 1923, Sir Roderick Jones, head of Reuters, and his wife, playwright and novelist Enid Bagnold, were to add the adjacent Gothic House to the property, which became the inspiration and setting for her play The Chalk Garden).

His troubled son Philip, who became a successful portrait painter, died in 1926. His adored daughter Margaret (died 1953) married John William Mackail (1850–1945), the friend and biographer of Morris, and Professor of Poetry at Oxford from 1911 to 1916. Their children were the novelists Angela Thirkell and Denis Mackail, and the youngest, Clare Mackail.

In an edition of the boys' magazine, Chums (No. 227, Vol. V, 13 January 1897), an article on Burne-Jones stated that "....his pet grandson used to be punished by being sent to stand in a corner with his face to the wall. One day on being sent there, he was delighted to find the wall prettily decorated with fairies, flowers, birds, and bunnies. His indulgent grandfather had utilised his talent to alleviate the tedium of his favourite's period of penance."

Artistic career

[edit]Early years: Rossetti and Morris

[edit]

Burne-Jones once admitted that after leaving Oxford he "found himself at five-and-twenty what he ought to have been at fifteen". He had had no regular training as a draughtsman and lacked the confidence of science. But his extraordinary faculty of invention as a designer was already ripening; his mind, rich in knowledge of classical story and medieval romance, teemed with pictorial subjects, and he set himself to complete his set of skills by resolute labour, witnessed by his drawings. The works of this first period are all more or less tinged by the influence of Rossetti; but they are already differentiated from the elder master's style by their more facile though less intensely felt elaboration of imaginative detail. Many are pen-and-ink drawings on vellum, exquisitely finished, of which his Waxen Image (1856) is one of the earliest and best examples. Although the subject, medium and manner derive from Rossetti's inspiration, it is not the hand of a pupil merely, but of a potential master. This was recognised by Rossetti himself, who before long avowed that he had nothing more to teach him.[14]

Burne-Jones's first sketch in oils dates from this same year, 1856, and during 1857 he made for Bradfield College the first of what was to be an immense series of cartoons for stained glass. In 1858 he decorated a cabinet with the Prioress's Tale from Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, his first direct illustration of the work of a poet whom he especially loved and who inspired him with endless subjects. Thus early, therefore, we see the artist busy in all the various fields in which he was to labour.[14]

In the autumn of 1857 Burne-Jones joined Morris, Valentine Prinsep, J. R. Spencer Stanhope[15] and others in Rossetti's ill-fated scheme to decorate the walls of the Oxford Union. None of the painters had mastered the technique of fresco, and their pictures had begun to peel from the walls before they were completed. In 1859 Burne-Jones made his first journey to Italy. He saw Florence, Pisa, Siena, Venice and other places, and appears to have found the gentle and romantic Sienese more attractive than any other school. Rossetti's influence persisted and is visible, more strongly perhaps than ever before, in the two watercolours of 1860, Sidonia von Bork and Clara von Bork.[14] Both paintings illustrate the 1849 gothic novel Sidonia the Sorceress by Lady Wilde, a translation of Sidonia Von Bork: Die Klosterhexe (1847) by Johann Wilhelm Meinhold.[16]

Painting

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2022) |

In 1864, Burne-Jones was elected an associate of the Society of Painters in Water-Colours—which is known as the Old Water-Colour Society—and exhibited, among other works, The Merciful Knight, the first picture which fully revealed his ripened personality as an artist. The next six years saw a series of fine watercolours at the same gallery.[14]

In 1866, Mrs. Cassavetti commissioned Burne-Jones to paint her daughter, Maria Zambaco, in Cupid finding Psyche, an introduction which led to their tragic affair. In 1870, Burne-Jones resigned his membership following a controversy over his painting Phyllis and Demophoön. The features of Maria Zambaco were clearly recognisable in the barely draped Phyllis, and the undraped nakedness of Demophoön coupled with the suggestion of female sexual assertiveness offended Victorian sensibilities. Burne-Jones was asked to make a slight alteration, but instead "withdrew not only the picture from the walls, but himself from the Society".[17][18] During the next seven years, 1870–1877, only two works of the painter's were exhibited. These were two water-colours, shown at the Dudley Gallery at the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly in 1873, one of them being the beautiful Love Among the Ruins, destroyed twenty years later by a cleaner who supposed it to be an oil painting, but afterwards reproduced in oils by the painter. This silent period was one of unremitting production.[citation needed]

Hitherto, Burne-Jones had worked almost entirely in watercolours. He now began pictures in oils, working at them in turn, and having them on hand. The first Briar Rose series, Laus Veneris, the Golden Stairs, the Pygmalion series, and The Mirror of Venus are among the works planned and completed, or carried far towards completion, during these years.[14]

The beginnings of Burne-Jones' partnership with the fine-art photographer Frederick Hollyer, whose reproductions of paintings and—especially—drawings would expose an audience to Burne-Jones's works in the coming decades, began during this period.[19]

At last, in May 1877, the day of recognition came with the opening of the first exhibition of the Grosvenor Gallery, when the Days of Creation, The Beguiling of Merlin, and the Mirror of Venus were all shown. Burne-Jones followed up the signal success of these pictures with Laus Veneris, the Chant d'Amour, Pan and Psyche, and other works, exhibited in 1878. Most of these pictures are painted in brilliant colours.[citation needed]

A change is noticeable in 1879 in the Annunciation and in the four pictures making up the second series of Pygmalion and the Image; the former of these, one of the simplest and most perfect of the artist's works, is subdued and sober; in the latter, a scheme of soft and delicate tints was attempted, not with entire success. A similar temperance of colours marks The Golden Stairs, first exhibited in 1880.[citation needed]

The almost sombre Wheel of Fortune was shown in 1883, followed in 1884 by King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid, in which Burne-Jones once more indulged his love of gorgeous colour, refined by the period of self-restraint. He next turned to two important sets of pictures, The Briar Rose and The Story of Perseus, although these were not completed.[14]

Decorative arts

[edit]

In 1861, William Morris founded the decorative arts firm of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. with Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Ford Madox Brown and Philip Webb as partners, together with Charles Faulkner and Peter Paul Marshall, the former of whom was a member of the Oxford Brotherhood, and the latter a friend of Brown and Rossetti.[9] The prospectus set forth that the firm would undertake carving, stained glass, metal-work, paper-hangings, chintzes (printed fabrics), and carpets.[14] The decoration of churches was from the first an important part of the business. The work shown by the firm at the 1862 International Exhibition attracted notice, and later it was flourishing. Two significant secular commissions helped establish the firm's reputation in the late 1860s: a royal project at St. James's Palace and the "green dining room" at the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert) of 1867 which featured stained glass windows and panel figures by Burne-Jones.[21]

In 1871 Morris & Co. were responsible for the windows at All Saints, designed by Burne-Jones for Alfred Baldwin, his wife's brother-in-law. The firm was reorganised as Morris & Co. in 1875, and Burne-Jones continued to contribute designs for stained glass and later tapestries until the end of his career. Nine windows designed by him and made by Morris & Co were installed in Holy Trinity Church in Frome.[22] Stained glass windows in the Christ Church cathedral and other buildings in Oxford are by Morris & Co. with designs by Burne-Jones.[23][24] Other windows are in St. Philip's Cathedral, Birmingham, Church of St Editha, Tamworth, Salisbury Cathedral, St Martin in the Bull Ring, Birmingham, Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, Chelsea, St Peter and St Paul parish church in Cromer, St Martin's Church in Brampton, Cumbria (the church designed by Philip Webb), St Michael's Church, Brighton, Trinity Church in Frome, All Saints, Jesus Lane, Cambridge, St Edmund Hall, St Anne's Church, Brown Edge, Staffordshire Moorlands, Kelvinside Hillhead Parish Church, Glasgow and St Edward the Confessor church at Cheddleton Staffordshire.

Stanmore Hall was the last major decorating commission executed by Morris & Co. before Morris's death in 1896. It was the most extensive commission undertaken by the firm, and included a series of tapestries based on the story of the Holy Grail for the dining room, with figures by Burne-Jones.[25]

In 1891 Jones was elected a member of the Art Workers Guild.

Illustration

[edit]Although known primarily as a painter, Burne-Jones was active as an illustrator, helping the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic to enter mainstream awareness. He designed books for the Kelmscott Press between 1892 and 1898. His illustrations appeared in the following books, among others:[26]

- The Fairy Family by Archibald MacLaren (1857)

- The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam by William Morris (1872)

- The Earthly Paradise by William Morris (not completed)

- The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer by Geoffrey Chaucer (1896)

- Bible Gallery by Dalziel (1881)

Design for the theatre

[edit]In 1894, theatrical manager and actor Henry Irving commissioned Burne-Jones to design sets and costumes for the Lyceum Theatre production of King Arthur by J. Comyns Carr, who was Burne-Jones's patron and the director of the New Gallery as well as a playwright. The play starred Irving as King Arthur and Ellen Terry as Guinevere, and toured America following its London run.[27][28][29] Burne-Jones accepted the commission with enthusiasm, but was disappointed with much of the final result. He wrote confidentially to his friend Helen Mary Gaskell (known as May), "The armour is good—they have taken pains with it ... Perceval looked the one romantic thing in it ... I hate the stage, don't tell—but I do."[30]

Aesthetics

[edit]

Burne-Jones's paintings were one strand in the evolving tapestry of Aestheticism from the 1860s through the 1880s, which considered that art should be valued as an object of beauty engendering a sensual response, rather than for the story or moral implicit in the subject matter. In many ways, this was antithetical to the ideals of Ruskin and the early Pre-Raphaelites.[31] Burne-Jones's aim in art is best given in his own words, written to a friend:

I mean by a picture a beautiful, romantic dream of something that never was, never will be – in a light better than any light that ever shone – in a land no one can define or remember, only desire – and the forms divinely beautiful – and then I wake up, with the waking of Brynhild.[14]

Final years

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2022) |

Burne-Jones was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1885, and the following year he exhibited uniquely at the Academy, showing The Depths of the Sea, a painting of a mermaid carrying down with her a youth whom she has unconsciously drowned in the impetuosity of her love. This picture adds to the habitual haunting charm a tragic irony of conception and a felicity of execution which give it a place apart among Burne-Jones's works. He formally resigned his Associateship in 1893.

One of the Perseus series was exhibited in 1887 and two more in 1888, with The Brazen Tower, inspired by the same legend. In 1890 the second series of The Legend of Briar Rose were exhibited by themselves and won admiration. The huge watercolour, The Star of Bethlehem, painted for the corporation of Birmingham, was exhibited in 1891.

A long illness for a time checked the painter's activity, which, when resumed, was much occupied with decorative schemes. An exhibition of his work was held at the New Gallery in the winter of 1892–1893. To this period belong his comparatively few portraits.

In 1894, Burne-Jones was made a baronet. Ill health again interrupted the progress of his works, chief among which was the vast Arthur in Avalon. William Morris died in 1896, and the health of Burne-Jones declined substantially after. In 1898 he suffered an attack of influenza, and had apparently recovered when he was again taken suddenly ill and died on 17 June 1898.[14][32] His memorial service was held six days later, at Westminster Abbey. His ashes were interred in the churchyard at St Margaret's Church, Rottingdean,[33] a place he knew through summer family holidays. In the winter following his death, a second exhibition of his works was held at the New Gallery, and an exhibition of his drawings at the Burlington Fine Arts Club.[14]

Honours

[edit]

In 1881 Burne-Jones received an honorary degree from Oxford, and was made an Honorary Fellow in 1882.[8] In 1885 he became the President of the Birmingham Society of Artists. At about that time, he began hyphenating his name, merely—as he wrote later—to avoid "annihilation" in the mass of Joneses.[34] In November 1893, he was approached to see if he would accept a Baronetcy on the recommendation of the outgoing Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone, the following February he legally changed his name to Burne-Jones.[35] He was formally created a baronet of Rottingdean, in the county of Sussex, and of the Grange, in the parish of Fulham, in the county of London, in the baronetage of the United Kingdom on 3 May 1894,[36] but remained unhappy about accepting the honour, which disgusted his socialist friend Morris and was scorned by his equally socialist wife Georgiana.[34][35] Only his son Philip, who mixed with the set of the Prince of Wales and would inherit the title, truly wanted it.[35] Burne-Jones was made an elected member of the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium in 1897.[37]

Following Burne-Jones' death, and at the intervention of the Prince of Wales, his memorial service was held at Westminster Abbey. It was the first time an artist had been so honoured.

Influence

[edit]

Burne-Jones exerted a considerable influence on French painting. He was influential among French symbolist painters, from 1889.[38] His work inspired poetry by Algernon Charles Swinburne – Swinburne's 1866 Poems & Ballads is dedicated to Burne-Jones.

Three of Burne-Jones's studio assistants, John Melhuish Strudwick, T. M. Rooke and Charles Fairfax Murray, went on to successful painting careers. Murray later became an important collector and respected art dealer. Between 1903 and 1907 he sold a great many works by Burne-Jones and the Pre-Raphaelites to the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, at far below their market worth. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery now has the largest collection of works by Burne-Jones in the world, including the massive watercolour Star of Bethlehem, commissioned for the Gallery in 1897. The paintings are believed by some to have influenced the young J. R. R. Tolkien, then growing up in Birmingham.[39]

Burne-Jones was also a very strong influence on the Birmingham Group of artists, from the 1890s onwards.

Neglect and rediscovery

[edit]On 16 June 1933, Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, a nephew of Burne-Jones, officially opened the centenary exhibition featuring Burne-Jones's drawings and paintings at the Tate Gallery in London. In his opening speech at the exhibition, Baldwin expressed what the art of Burne-Jones stood for:

In my view, what he did for us common people was to open, as never had been opened before, magic casements of a land of faery in which he lived throughout his life ... It is in that inner world we can cherish in peace, beauty which he has left us and in which there is peace at least for ourselves. The few of us who knew him and loved him well, always keep him in our hearts, but his work will go on long after we have passed away. It may give its message in one generation to a few or in other to many more, but there it will be for ever for those who seek in their generation, for beauty and for those who can recognise and reverence a great man, and a great artist.[40]

But, in fact, long before 1933, Burne-Jones had fallen out of fashion in the art world, much of which soon preferred the major trends in Modern art, and the exhibit marking the 100th anniversary of his birth was a sad affair, poorly attended.[41] It was not until the mid-1970s that his work began to be re-assessed and once again acclaimed, following the publication of Martin Harrison and Bill Waters' 1973 monograph and reappraisal 'Burne-Jones'. In 1975, author Penelope Fitzgerald published a biography of Burne-Jones, her first book.[42] A major exhibit in 1989 at the Barbican Art Gallery, London (in book form as: John Christian, The Last Romantics, 1989), traced Burne-Jones's influence on the subsequent generation of artists, and another at Tate Britain in 1997 explored the links between British Aestheticism and Symbolism.[38]

A second, lavish centenary exhibit – this time marking the 100th anniversary of Burne-Jones's death – was held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1998, before travelling to the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery and the Musée d'Orsay, Paris.[43]

Fiona MacCarthy, in a review of Burne-Jones's legacy, notes that he was "a painter who, while quintessentially Victorian, leads us forward to the psychological and sexual introspection of the early twentieth century".[44]

Gallery

[edit]Stained and painted glass

[edit]-

Cartoon for Daniel window, St. Martin's-on-the-Hill, Scarborough, 1873

-

The Worship of the Magi window, 1882, Trinity Church, Boston

-

The Worship of the Shepherds window, 1882, Trinity Church, Boston

-

Nativity scene in St Mary's Church, Huish Episcopi, Somerset

-

David, 1872, in St Michael and All Angels, Waterford, Hertfordshire

-

Miriam, 1872, in St Michael and All Angels, Waterford, Hertfordshire

-

Justice, Church of St. Andrew and St. Paul, Montreal

-

Miriam, 1886, in St Giles' Cathedral, Edinburgh

-

Christ as Salvator Mundi, 1896, in St Michael and All Angels, Waterford, Hertfordshire

-

St. Cecilia window, Second Presbyterian Church, Chicago, Illinois

-

Crucifixion window in St James's Church, Staveley, Cumbria

-

Angel window in St. James's Church, Staveley, Cumbria

-

Faith in the Old West Kirk, Greenock

-

Music in the Old West Kirk, Greenock

-

St Agnes of Rome and Catherine of Alexandria, St Paul, Irton

-

The Ascension, 1898, Jesus Church, Troutbeck, Cumbria

Drawings

[edit]-

The Knight's Farewell, pen-and-ink on vellum, 1858

-

Going to the Battle, pen-and-ink with grey wash on vellum, 1858

-

King Sigurd, wood-engraving by the Dalziel Bros. after a pen-and-ink drawing, 1862

-

Portrait of Ignacy Jan Paderewski, 1892

Paintings

[edit]Early works

-

The Merciful Knight, 1863

-

The Princess Sabra Led to the Dragon, 1866

-

Portrait of Maria Zambaco, 1870

-

Phyllis and Demophoön, 1870

-

Temperantia, 1872

Pygmalion (first series)

-

The Heart Desires, 1868–1870

-

The Hand Refrains, 1868–1870

-

The Godhead Fires, 1868–1870

-

The Soul Attains, 1868–1870

Pygmalion and the Image (second series)

-

The Heart Desires, 1878

-

The Hand Refrains, 1878

-

The Godhead Fires, 1878

-

The Soul Attains, 1878

The Grosvenor Gallery years

-

Pan and Psyche, 1874

-

An Angel Playing a Flageolet, 1878

-

The Annunciation, 1879

-

The Angel, 1881

-

The Mill, 1882

The Legend of Briar Rose (second series)

-

The Briar Wood, completed 1890

-

The Council Chamber, 1890

-

The Garden Court, 1890

-

The Rose Bower, 1890

Later works

-

The Garden of Pan, 1886-87, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

-

The Doom Fulfilled, 1888 (Perseus Cycle 7)

-

The Baleful Head, 1887 (Perseus Cycle 8)

-

The Star of Bethlehem, 1890

-

Vespertina Quies, 1893

-

Love Among the Ruins, 1873

-

The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon 1881–1898

Decorative arts

[edit]-

Illuminated manuscript of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam by William Morris, illustrated by Burne-Jones with a variant of Love Among the Ruins, 1870s

-

The Arming and Departure of the Knights, one of the Holy Grail tapestries, 1890s, figures by Burne-Jones.

-

A page from the Kelmscott Chaucer, decoration by Morris and illustration by Burne-Jones, 1896

Theatre

[edit]-

Scene from King Arthur, sets by Burne-Jones, 1895

-

Ellen Terry as Guinevere, costume by Burne-Jones, 1894

Photographs

[edit]-

The Burne-Jones and Morris families in the garden at the Grange, 1874, photograph by Frederick Hollyer

-

Edward Burne-Jones, c. 1882 (Hollyer)

-

Georgiana Burne-Jones, c. 1882 (Hollyer)

-

Burne-Jones's garden studio at the Grange, 1887 (Hollyer)

| External videos | |

|---|---|

All at Smarthistory[45] |

See also

[edit]- List of paintings by Edward Burne-Jones

- The Flower Book

- Stained Glass Designs for the Vinland House, 1881

References

[edit]- Notes

- Citations

- ^ "Burne-Jones". Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ Lehnebach, Carlos A.; Regnault, Claire; Rice, Rebecca; Awa, Isaac Te; Yates, Rachel A. (1 November 2023). Flora: Celebrating our Botanical World. Te Papa Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-1-9911509-1-2.

- ^ a b c Millington, Ruth. "Edward Burne-Jones and The Legend of the Briar Rose". Birmingham Museums. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Wildman 1998, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Daly 1989, pp. 249–251.

- ^ Newall, Christopher. "Jones, Sir Edward Coley Burne-, first baronet (1833–1898)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4051. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Rose 1981, p. 78.

- ^ a b c Ward, Thomas Humphry (1901). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ a b Mackail, John William (1901). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Wildman 1998, p. 107.

- ^ a b Wildman 1998, p. 114.

- ^ Flanders 2001, pp. 118–120.

- ^ Flanders 2001, p. 136.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Burne-Jones, Sir Edward Burne". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 848–850.

- ^ Marsh 1996, p. 110.

- ^ Wildman 1998, p. 66.

- ^ Roget 1891, p. 116.

- ^ Wildman 1998, p. 138.

- ^ Wildman 1998, pp. 197–198.

- ^ "Saint Cecilia (y1974–84)". Princeton University Art Museum. Princeton University.

- ^ Parry 1996, pp. 139–140, Domestic Decoration.

- ^ "Burne-Jones Windows – Holy Trinity Frome". Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ Edward Burne-Jones Archived 24 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine Southgate Green Association "His work included both stained-glass windows for Christ Church in Oxford and the stained glass windows for Christ Church on Southgate Green."

- ^ PreRaphaelite Painting and Design Archived 14 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine University of Texas

- ^ Parry 1996, pp. 146–147, Domestic Decoration.

- ^ Souter & Souter 2012, p. 19.

- ^ Wildman 1998, p. 315.

- ^ Wood 1999, p. 119.

- ^ "Miss Terry as Guinevere; In a Play by Comyns Carr, Dressed by Sir Edward Burne-Jones". The New York Times. 5 November 1895. Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- ^ Wood 1999, p. 120.

- ^ Wildman 1998, pp. 112–113.

- ^ "No. 26988". The London Gazette. 19 July 1898. p. 4396.

- ^ Dale 1989, p. 212.

- ^ a b Taylor 1987, pp. 150–151.

- ^ a b c Flanders 2001, p. 258.

- ^ "No. 26509". The London Gazette. 4 May 1894. p. 2613.

- ^ Index biographique des membres et associés de l'Académie royale de Belgique (1769–2005). p 44

- ^ a b "The Age of Rossetti, Burne-Jones and Watts: Symbolism in Britain 1860–1910". Archived from the original on 28 March 2006. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ^ Bracken, Pamela (4 March 2006). "Echoes of Fellowship: The PRB and the Inklings". Conference paper, C. S. Lewis & the Inklings. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Centenary exhibition of Sir Edward Burne-Jones at London Tate Gallery". The Straits Times. 24 July 1933. p. 6.

- ^ Wildman 1998, p. 1.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1975.

- ^ Wildman 1998, Front matter.

- ^ Tate: "A Visionary Oddity: Fiona MacCarthy on Edward Burne-Jones"

- ^ "Burne-Jones's Hope". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Dale, Antony (1989). Brighton churches. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00863-8.

- Daly, Gay (1989). Pre-Raphaelites in Love. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 978-0-89919-450-9.

- Fitzgerald, Penelope (1975). Edward Burne-Jones: a biography. London: Joseph. ISBN 0718113675. OCLC 2006197.

- Flanders, Judith (2001). A Circle of Sisters: Alice Kipling, Georgiana Burne-Jones, Agnes Poynter and Louisa Baldwin. W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-05210-7.

- Marsh, Jan (1996). The Pre-Raphaelites: their lives in letters and diaries. Collins & Brown. ISBN 978-1-85585-246-4.

- Parry, Linda, ed. (1996). William Morris. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-4282-8.

- Roget, John Lewis (1891). A History of the "Old Water-Colour" Society, Now the Royal Society of Painters in Water Colours. Vol. 2. Longmans Green.

- Rose, Andrea (1981). Pre-Raphaelite portraits. Oxford: Oxford Illustrated Press. ISBN 0-902280-82-1.

- Taylor, Ina (1987). Victorian Sisters. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-79065-5.

- Wildman, Stephen (1998). Edward Burne-Jones: Victorian Artist-Dreamer. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-859-5.

- Wood, Christopher (1999). Burne-Jones: the life and works of Sir Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898). London: Phoenix Illustrated. ISBN 0-7538-0727-0.

- Souter, Tessa; Souter, Nick (2012). The Illustration Handbook: A guide to the world's greatest illustrators. Oceana. ISBN 9781845734732.

Further reading

[edit]- MacCarthy, Fiona (2011). The Last Pre-Raphaelite: Edward Burne-Jones and the Victorian Imagination. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-22861-4.

- Clarke, Brian (2011). Burne-Jones: Vast acres and fleeting ecstasies. The Journal of Stained Glass, Vol. XXXV. The British Society of Master Glass Painters. ISBN 978-0-9568762-1-8

- Arscott, Caroline. William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones: Interlacings, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press (Published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art), 2008). ISBN 978-0-300-14093-4.

- Mackail, J. W. (1899). The Life of William Morris in two volumes. London, New York and Bombay: Longmans, Green and Co. Volume I and Volume II (1911 reprint)

- Mackail, J. W. (1901). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). Vol. 3. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 197–203.

- Marsh, Jan, Jane and May Morris: A Biographical Story 1839–1938, London, Pandora Press, 1986 ISBN 0-86358-026-2.

- Marsh, Jan, Jane and May Morris: A Biographical Story 1839–1938 (updated edition, privately published by author), London, 2000.

- Marsh, Jan (2018). The Illustrated Letters and Diaries of the Pre-Raphaelites (Illustrated ed.). Batsford. ISBN 978-1849944960.

- Robinson, Duncan (1982). William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and the Kelmscott Chaucer. London: Gordon Fraser.

- Spalding, Frances (1978). Magnificent Dreams: Burne-Jones and the Late Victorians. Oxford: Phaidon. ISBN 0-7148-1827-5.

- Todd, Pamela (2001). Pre-Raphaelites at Home. New York: Watson-Guptill. ISBN 0-8230-4285-5.

External links

[edit]- Online Burne-Jones Catalogue Raisonné

- Works by Edward Burne-Jones at Faded Page (Canada)

- 84 artworks by or after Edward Burne-Jones at the Art UK site

- Profile on Royal Academy of Arts Collections

- The Age of Rossetti, Burne-Jones and Watts: Symbolism in Britain 1860–1910 Online version of exhibit at the Tate Britain 16 October 1997 – 4 January 1998, with 100 works by Burne-Jones, at Art Magick

- Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery's Pre-Raphaelite Online Resource Archived 22 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine Large online collection of the works of Edward Burne Jones

- Lady Lever Art Gallery

- The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon (1881) in the Museo de Arte de Ponce

- Pre-Raphaelite online resource project website Archived 29 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine at the Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery, with about a thousand paintings on canvas and works on paper by Edward Burne-Jones

- Burne-Jones Stained Glass Windows in Cumbria

- The Pre-Raphaelite Church – Brampton

- Some Burne-Jones stained glass designs

- Stained Glass Window Designs for the Vinland Estate, Newport, Rhode Island, 1881.

- Speldhurst Church

- Phryne's list of pictures in public galleries in the UK

- Mary Lago Collection Archived 19 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine at the University of Missouri Libraries. Personal papers of a Burne-Jones scholar.

- 1833 births

- 1898 deaths

- 19th-century English painters

- English male painters

- English stained glass artists and manufacturers

- Pre-Raphaelite painters

- Christian artists

- Artists from Birmingham, West Midlands

- People from Fulham

- Alumni of Exeter College, Oxford

- People educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham

- Associates of the Royal Academy

- Members of the Royal Academy of Belgium

- Baronets in the Baronetage of the United Kingdom

- Artists' Rifles soldiers

- Morris & Co.

- Alumni of the Birmingham School of Art

- Burne-Jones family

- English mosaic artists

- English businesspeople

- English designers

- English company founders

- Manufacturing company founders

- Artists awarded knighthoods

- Painters from the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham